- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

The cycle continues

Welding instructor returns to his roots to lead program to excellence

- By Amanda Carlson

- July 29, 2015

- Article

- Arc Welding

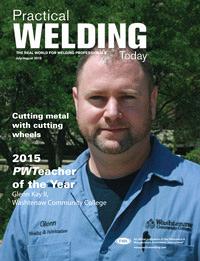

Glenn Kay II, this year’s PWTeacher of the Year award winner, isn’t just a teacher. He’s a coach, mentor, and living proof of what can happen when you are relentless in your hard work.

On the surface it would appear that Glenn Kay II, welding instructor and department chair of the welding and fabrication department at Washtenaw Community College, Ann Arbor, Mich., has it all—a prominent position at one of the state’s best community college welding programs that is 500+ students strong, plans for new equipment and a curriculum overhaul thanks to a supportive administration and a $4 million grant, and three former students who not only advanced to represent the U.S. at WorldSkills, but finished no worse than second place at their respective competitions.

It would appear that Kay is living the dream, and in many ways he probably is. But in no way should that imply that the road leading up to this point has been easy. It is the result when you mix a competitive spirit with a tireless work ethic, and that’s why he is our PWTeacher of the Year for 2015.

The Method Behind the Madness

To understand why Kay is the way he is, we have to start from the very beginning. He doesn’t remember a time when he didn’t work. He recalls helping with his family’s floor covering business at age 7 or 8, carrying boxes of tile, rolls of carpet, or tools during the summers or on weekends. Bigger jobs required that he help out after school too. He never questioned it; it was just part of the normal routine.

In high school after switching his mandatory elective from Spanish to welding three weeks into his junior year, an unexpected challenge from his welding instructor fed right into his competitive nature.

“From Day No. 1 my instructor put me on the spot. He brought us over and showed us some beads and, of course, being that I was starting three weeks later than everyone else, he made me run a bead. I had no idea what I was doing. Everyone laughed and it was funny, but I also took it as a challenge. I wanted to get it, and that moment he really got my attention,” Kay explained.

He pressed on, enjoying the challenge and soaking up as much as he could from his instructor. He spent more time welding and less time helping out with the family floor covering business. He offered his welding services to a neighbor who owned a small trucking company. And finally, with his teacher’s help, he and a few others from class landed jobs at Vulcanmasters Welding Co., a custom fabricating and welding firm in Detroit. He also competed in high school SkillsUSA competitions and local AWS-sponsored competitions, even earning a scholarship for college.

When he began his studies at Washtenaw Community College, Kay worked full time for Vulcanmasters. He was also committed to competing in SkillsUSA. Most people wouldn’t be able to sustain the schedule he kept up for very long, but again, hard work was nothing new.

“I was at school seven days a week. I’d get out of work, drive here, and take classes from 5 p.m. to 10 p.m. I lived an hour away so then I’d have to drive an hour back home. I did that for three years.”

It was a juggling act for sure, but one Kay could handle. Until, that is, competing in SkillsUSA got serious. In 1996, his first year at Washtenaw, he placed first at the postsecondary state Skills-USA competition and qualified for nationals, where he would eventually take fifth place. It wasn’t the finish he was hoping for, but it was good enough for him to qualify for the pretrial, reserved for the top 12 finishers.

The pretrial process required competitors to submit a project once a month for eight months, cutting the field in half from 12 welders to six. It’s a grueling process, and Kay was working and going to school full time and spending every free moment practicing and submitting his projects.

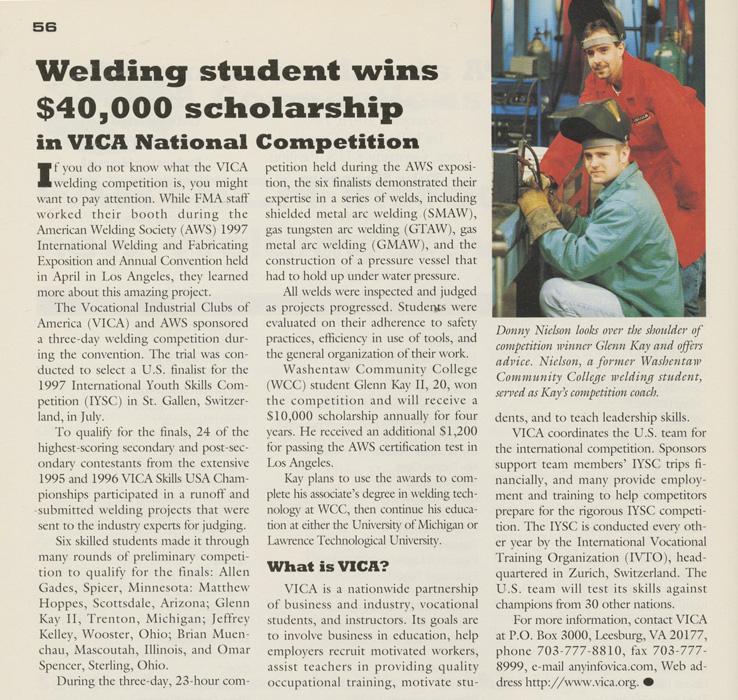

At age 20, Kay and his welding achievements were highlighted in Practical Welding Today’s very first issue, July/August 1996.

“I had to make a decision. I knew that if I wanted to continue with the process that I would have to give it 110 percent or else I would be wasting my time. Should I continue to work full time or should I compete in SkillsUSA? Sending in projects, staying at school ‘til 10 or 11 at night, getting projects in on deadline and to meet the criteria, it was tough.

“I was never able to not work. I had to pay my own way for everything—food, school tuition, everything.”

After receiving word that he had placed first in the pretrial process, Kay decided to quit working and devote every free moment to training for the next phase, the weld-off. For the month and a half leading up to the weld-off, he was in the lab from 8 a.m. to 11 p.m. It was nonstop. He even squeezed in a welding session in the morning before he flew out to compete. But it was all worth it as Kay took first place and earned the right to represent the U.S. at the international competition. He also earned a $40,000 scholarship to use toward furthering his education.

He spent a few months training with equipment manufacturers and Skills-USA supporters like Miller Electric and Lincoln Electric, among others. Each visit yielded job offers. He was only 18 years old and hadn’t yet earned his associate degree.

After placing fifth at the international competition in Switzerland—which to this day still bothers him—he came home, finished his associate degree, and put his scholarship money toward a bachelor’s degree in business management from Cleary University. He took classes at night while working full time at a fab shop by day. He graduated from college debt-free.

The Biggest Job of All

Kay spent several years out in industry before he returned to Washtenaw as a temporary part-time instructor, where he spent two years teaching while working as a full-time welder for DTE Energy. In that time he credits his experience at Washtenaw and competing in SkillsUSA for opening a lot of doors and preparing him for the rigors of the real world. He was never afraid of passing a weld test. He never feared not having a job.

“I never looked for work, it always came to me. I’ve never been laid off, unemployed, and the next job I’ve taken was always a step forward.”

These are lessons, he found, that he felt he could share with others.

For two years he taught on a part-time basis when changes at DTE left him working nights. It was tough, but he still managed to do both for a little while, at least until his first child was born. At that point he alerted the college of his intention to step down from the part-time gig to spend more time with family.

Shortly thereafter, however, a permanent full-time teaching position became available.

Former students and WorldSkills silver medalists Alex Pazkowski (far left) and Brad Clink (far right) counsel a current student regarding a project. Both, thanks to Kay, have found their way back to Washtenaw Community College and intend to share their experiences with the next batch of students.

“It was one of the hardest decisions of my life—picking between the two jobs. I loved my job at the power plant and I enjoyed the people I worked with. But I was passionate about sharing with others what I’ve learned through my own experiences. I found it was way more rewarding than working at the power plant, even though that was a phenomenal job.

“It was a little bit of a pay cut to come here, but in the end it was totally worth it.”

Every day as a welding instructor is different. Between juggling teaching responsibilities and managing staff, he must ensure that the more than 500 students enrolled during the fall and spring semesters (and around 200 in the summer semester) are getting their needs met. This is no easy task because the classes comprise a full spectrum of students from all walks of life.

“There’s the students who went to work right out of high school and found that what they were doing wasn’t quite right for them. And we’ll get the middle-aged folks who come in, so they’re still working and coming in at night. They’re pretty focused. Then you get the people who may have had a really good job but lost it once the economy turned.”

Kay also must foster outreach efforts with local high schools, organize and host an annual open house complete with a welding competition for local high schools, host high school and postsecondary welding competitions, and perform duties as needed with his local AWS chapter. All this in addition to connecting current students with jobs and counseling them about the importance of finishing their associate degree.

“We’ve had companies come in and take 40 students at one time. While it’s great for the students, it definitely hurts our completion rate. But what we’ve found is those students will trickle back in, take night classes, and work around a schedule because they realize after being out there how important it is to continue to learn more. We really promote that on their first day. We want them to know that we can be flexible when they get that first job. We want to do everything we can to make it possible for students to finish.”

In summary, there’s a lot to do, but luckily he has experience with multitasking and little sleep.

A couple of new challenges have presented themselves to Kay over the last year. First, the welding department had to make do with one less full-time instructor. The ideal number of full-time instructors for a program of this size is three; however, when one instructor left last August, Kay had to scramble to find a temporary full-time instructor to help shoulder the load. Kay reached out to Brad Clink, a former WCC student, who accepted the position.Another challenge arrived this spring when the Michigan Economic Development Corporation awarded the college a $4.4 million grant through the Community College Skilled Trades Equipment Program, an effort to help close a talent gap and meet a demand for good-paying jobs. It was a much needed grant that will help other vocational programs at the college, but specifically the welding program. With the grant the welding department will revamp the curriculum with new, technologically up-to-date equipment, increase the number of welding booths from 60 to 76, and improve existing booths.

The grant required a $2 million match from the college, which was no easy task, but showed its commitment to the welding program, said Brandon Tucker, dean of the advanced technologies and public service careers division.

Washtenaw Community College secured a $4.4 million grant from the Michigan Economic Development Corporation to, among other things, help the welding program purchase new equipment and revamp its curriculum in an effort to provide training that closely aligns with the current needs of the industry.

“We had to take $2 million from the general fund and set it aside just to be able to accept the grant. Out of a $98 million budget, [$2 million] is a lot of money, and I think they recognized the need. I give a lot of credit to the faculty because they came and presented to the board along with me, and I think they saw the need. We’re committed to welding as an institution and also to advanced technology,” Tucker said.

Kay hopes to integrate necessary equipment that will mirror the technology used in local industry and to perform a major overhaul that would add three new degree programs—welding and fabrication, welding and cutting automation, and testing and inspection.

“That way the student who comes into the program not wanting to be under the hood welding could still contribute and use their skill sets. Or maybe the younger generation sees the technology behind inspection and testing and gets excited about that.”

When Welding Becomes Competitive

or the student welders who participate in the various postsecondary SkillsUSA competitions, holding the distinction as one of the top student welders in the country is an incredible feat. Following through with the rigorous, months-long weeding-out process only to be whittled down to the top six would, for some, be a career benchmark. Others still might be satisfied with advancing to the pretrial process, which is set aside for the final three welders who will then compete to advance to WorldSkills, held every two years.

But to win and represent the U.S. at the prestigious WorldSkills competition and earn a $40,000 scholarship? That is a life-changing achievement that only a select few students can boast of.

For many welding instructors, to have one of his or her students advance and move on in this process would be an absolute dream. Kay has guided three students to this achievement after having done it himself as a student welder.

Some might call that a coincidence, while others might raise a speculative eyebrow and cry foul. But those who know the three welders and, more specifically, Kay, understand. His workaholic tendencies and strong competitive nature drove him to excellence as a student welder, so why, now 19 years later, wouldn’t he demand the same work ethic, drive, and competitiveness from his students? He’d consider anything less a waste of time.

First came Joe Young, a student who shared Kay’s work ethic.

“Joe was full of energy. His family business was landscaping, so they’re workaholics, and when I required that, it was no big deal to him. He was very open to doing whatever it takes.”

Young went on to qualify for WorldSkills in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, where he won a silver medal. When he came back he began teaching at Washtenaw alongside Kay.

With the grant, Kay plans to purchase more automated cutting equipment, including a laser, and implement a welding and cutting automation degree program.

Not far behind was Clink, a Saline, Mich., native who started welding in high school to learn how to repair equipment for his family’s landscaping company, where he planned to work after graduation. But the articulated credits he had earned from his high school welding program in conjunction with WCC meant that it would take him only a year and a half to earn his associate degree, so he opted for that route.

Alex Pazkowski, also from Saline, Mich., said he went to Washtenaw specifically to become the best welder in the world. He had aspirations of competing at WorldSkills and bringing home the gold medal.

Together Kay and Young trained Clink and Pazkowski, which meant more long hours in the welding lab. The two competed at the state SkillsUSA tournament a year apart (because Clink is a year older) and competed in separate nationals as well.

“Brad did one better than me at nationals and took fourth, but Alex got the first gold medal that we’ve ever had at nationals,” Kay said.

Each of their respective performances at nationals earned them a spot in the top 12, and both eventually made the cut from six to the final three. And that was when the questions began.

With Washtenaw having two of the top three welders in the competition, Kay said people were mad, claiming the competition was fixed in WCC’s favor. It was disheartening but neither Kay, his support staff, nor his students felt like they had anything to be ashamed of. The formula for success, while not easy, is very simple.

“It’s no secret why we build the best welders in the country. The instructors and students are dedicated; we have a supportive institution behind us; and the students know that their hard work will never fail them but instead it will bring about the greatest benefit and change their lives, regardless of what place they get. Students that go down this road are successful because they go the extra mile and reap the benefits of advancing their skills by putting even greater time under the hood than they already experience in our classes,” Kay explained.

Said Pazkowski: “We worked incredibly hard leading up to competitions—Brad did 90-hour weeks, I did 88-hour weeks because I liked to sleep in on Sundays. He was here at 8 a.m. and I came in at 10 a.m.”

Clink eventually won, beating out his friend Pazkowski and another student. He went on to take the silver medal at WorldSkills in London in 2011. Pazkowski started the process all over again and followed in the footsteps of Kay, Young, and Clink by qualifying for WorldSkills two years later in Germany. He, too, earned a silver medal.

“It’s funny to take a step back and reflect on the three of them and on how it all played out. It’s really kind of amazing,” Kay said.

It’s not uncommon for area companies to hire away Washtenaw welding students before they have earned their associate degree. Kay of all people understands a person’s desire to work and make money; however, he strongly encourages them to take advantage of the program’s flexible schedule to continue on their degree path.

From Student to Teacher: Coming Full Circle

While Kay does enjoy all of the work that is expected of him as welding department chair, it’s still the welding and the teaching that make him feel most at home, as well as the relationships he’s built with current and former students.

If you need proof, look no further than Clink and Pazkowski. Both walked away from that experience with $40,000 to finish college, and both had more job offers than they knew what to do with. Yet both have found their way back to the Washtenaw Community College welding department—Clink as a temporary full-time instructor and Pazkowski as full-time lab tech. Both could have chosen very different paths had it not been for welding and Kay’s mentorship.

Take Clink, for example. Remember, he was set on working for his family’s landscaping company after high school. That’s still an option, of course, but since his time at Washtenaw, he’s earned his bachelor’s degree in welding engineering from Ferris State University and has spent time working as a welding engineer in San Diego and Texas. Last year, however, he was made aware of the vacant welding instructor position at Washtenaw. It was an opportunity to return home, which, for the time being, is what he wanted.

“I know that the permanent full-time position is becoming available soon, and I’d like to try my luck at that. It was an easier decision to come back because [Kay] is here. I know his intentions for the program and where it is heading. I like his vision and I want to be a part of the team that helps make that happen,” Clink said.

Without Kay’s influence, Pazkowski’s journey could have been much different too. After losing to Clink in 2011, Pazkowski was ready to walk away from competing for good. After putting in months of 88-hour work weeks jam packed with nothing but welding only to fall short in the end, it was tough for him to fathom doing it all over again.

“I went into Glenn’s office after I lost—sometime in early 2012—and said, ‘Glenn, I’m done. I’m not going to do this again.’ If I went through it all again and lost, it would mean another two years that had gone to waste.

“Glenn said, ‘Nope, you can’t do that. You have to do it all again. There’s no guarantee you’ll win, but if you don’t do it again you’ll regret it.’ So I left his office that day having signed the papers to do it all again.”

Explained Kay: “Alex was pretty discouraged, but we talked him into doing it one more time because he was still age-eligible and his talent was unbelievable. He had a whole year less than Brad and he lost by a couple tenths of a point. I saw Alex as someone with the golden arm. He was our gold medal. He had such raw talent for it.”

Now a full-time lab technician at Washtenaw, working alongside Kay and Clink, Pazkowski said his dream job is to be a welding instructor at the college. He credits Kay for opening his eyes to the value of teaching someone a skill they can use for life.

“Glenn is like my Mr. Miyagi. When I first started competing, my goal was to be the best welder in the world. I was a cocky little high school kid who thought I could take on the world, and Glenn really brought me back down and got me on the right path.”

It’s rare for someone Pazkowski’s and Clink’s age to have the kind of perspective that allows them to understand the value of helping others over making money, but that’s exactly where they are thanks, in part, to Kay’s influence. And even though they are young, they have valuable experiences to pass on to the next batch of students.

“If you strive to become more knowledgeable and skilled, it will always be a part of you. I took that every day to the welding booth,” Clink said.

Now both Clink and Pazkowski are getting a glimpse of Kay the boss. It’s not uncommon for Clink to get a work-related text message from Kay around 10 or 11 p.m.—his brain never stops working or thinking of things that need to get done the next day or that week.

“As an instructor he’s pushing himself to take this program to the next level in the same way he pushed us during training for those welding competitions. And I’m up for that challenge. The crazy part is I’m awake and I respond to those text messages,” Clink said.

And the cycle continues.

In Their Words

“Glenn has an unwavering dedication to the program. Oftentimes I get e-mails from Glenn at 1 or 2 o’clock in the morning. Glenn has a family—he has a wife and three kids—and I think it shows the commitment he has to work all day, go home and take care of family, and then still turn on the lightbulb at night to do what he has to do as a department chair and as a faculty member. I think that’s a true testament to his love and dedication to the program. And we appreciate it.”

—Brandon Tucker, dean, Advanced Technologies and Public Service Careers Div.

“He takes a personal interest in his students and shows that he cares. I actually read a study that one of the biggest determining factors for a student’s success is whether or not they perceive the instructor likes them. I love that he talks to us, knows our names, helps us with job searching or resume building; he cares inside and outside the classroom.”

—Hope Wade, lab assistant/work study, current WCC student

“It’s hard to describe the kind of influence he’s had on me because he comes from a similar family background and our stories are so much the same. You take all of this time and energy to scale the side of a mountain, and sometimes you feel like you’ll never get to the top. You can look at Glenn and say yeah, there is. If I can keep climbing I’ll be there. He’s been a mentor and is an example of what milestones to hit.”

—Brad Clink, temporary full-time instructor, former WCC student, and WorldSkills silver medalist

“He made this program what it is to the point where I can comfortably say I would want to work here until I retire. He brings the best out of people and the people who work alongside him work their asses off to make sure it is what it needs to be. We’re still working on it; it’s not perfect and it never will be, but he’s done a good job.”

—Alex Pazkowski, full-time lab tech, former WCC student, and WorldSkills silver medalist

About the Author

Amanda Carlson

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8260

Amanda Carlson was named as the editor for The WELDER in January 2017. She is responsible for coordinating and writing or editing all of the magazine’s editorial content. Before joining The WELDER, Amanda was a news editor for two years, coordinating and editing all product and industry news items for several publications and thefabricator.com.

About the Publication

subscribe now

The Welder, formerly known as Practical Welding Today, is a showcase of the real people who make the products we use and work with every day. This magazine has served the welding community in North America well for more than 20 years.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Sheffield Forgemasters makes global leap in welding technology

Welding student from Utah to represent the U.S. at WorldSkills 2024

Lincoln Electric announces executive appointments

Engine-driven welding machines include integrated air compressors

ESAB unveils Texas facility renovation

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI