AWS CWI, CWE, NDE Level III

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Welding supply and equipment distributorships, then and now

- By Professor R. Carlisle "Carl" Smith

- June 12, 2013

- Article

- Arc Welding

Remember when there were Chevrolet dealers, Ford dealers, and Chrysler dealers? Most automobile dealerships were brand-exclusive—not one megadealership selling five or six different brands.

These dealerships were fierce competitors, and a town had only one dealership per brand. Price was not the object in a sale. It was “my brand is the best brand and has the best features.” The salesmen knew their products; automobile producers provided them with extensive training. Guys in my hometown would almost come to blows over which vehicle was best.

Chevrolet put the gear shifter on the steering column in 1939. Ford and Chrysler followed in 1940 (Figure 1). Ford was the first in the group to produce a V8 engine in 1932. Chevrolet came out with the overhead V6 cylinder in the early 1930s.

Chrysler created “floating power” with its suspension in 1937. It also was the first with hydraulic brakes and the semiautomatic transmission called “fluid drive” in the 1941 Dodge.

It was rare to see any of these brands in any colors other than black, dark blue, dark green, gray, or a two-tone of these colors until the 1950s.

The differences in vehicles were the things that attracted customers, not the price.

Tires were made in Akron, Ohio. Even tires for Sears, Roebuck, Montgomery Ward, and Spiegel were made by producers like Firestone, BFGoodrich, and Goodyear. Buyers selected the tires that were best for their use.

Other automobiles were on the market, but they never caught on like the Chevrolet, Ford, and Chrysler brands. American Motors (Willys), Nash, Hudson, and Henry J. Kaiser had several models (Kaiser, Frazer, Henry J). Kaiser even built an Allstate car that Sears, Roebuck sold.

So what does this car stuff have to do with welding supply distributors? Up until the early 1970s, distributorships were much like the automobile dealerships in their exclusivity. For many years each sizable geographic area had a dealer that sold one of the “Big Three”: Hobart, Lincoln, or Miller. Each manufacturer had selling points that were passed down by the factory representatives and used by the distributor salespeople.

Miller sometimes was a “floater” sold by the Hobart or Lincoln distributor. In the early years, the Miller Electric Company did not produce engine- or motor-driven machines. Its main machines were transformer and transformer/rectifier models. The Gold Star gas tungsten arc welding (GTAW) machine was the most popular in the Miller line.

Not All Machines Caught On

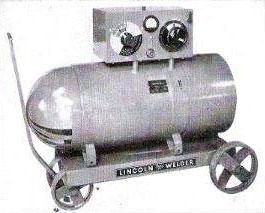

Miller and others actually built machines that should have caught on like wildfire, but didn’t. Miller’s contained a welding power source, a power generator, and an air compressor, all powered by a Chrysler Hemi engine.

Some other welding machines never really caught on. Westinghouse made a good machine, but never could sign on enough distributors to sell it, so the company used it in its own shops.

Airco sold some machines made by Miller and some by a company called Champion, which it attempted to sell through its gas and gas apparatus distributorships. Airco distributors were very competitive, especially when selling against Linde distributors.

Forney made a welding machine equipped with a carbon arc spot welding torch mainly for automobile shops. Auto parts dealers sold many of these machines.

Roots of GMAW

Hobart and Lincoln were the leaders in the electric welding machine business. Each had its own “best” product. Lincoln sold lots of motor generator (Figure 2) and engine-driven types of machines, and Hobart was close behind.

During the 1950s and ’60s, Hobart appeared to be the more innovative of the two companies. Hobart engineers continually looked for new and different products. The small, solid-wire, gas-shielded welding process was “owned” by Hobart and named “microwire” (Figure 3). The name stuck and is used even today by some of the old-timers in the business.

The process started out as the metallic inert gas (MIG) process, but CO2 gas, which was popular at the time, is not an inert gas. Therefore, an AWS committee changed the process name to gas metal arc welding (GMAW).

When this process was introduced, progressive distributorships sent their employees to Hobart to learn to use and service the new type of equipment. The training often lasted a month. When a distributor/student finished the training, he was the equivalent of a “welding technician,” or as Mr. Nickel (Sam Kiser) dubbed it, a “welding technologist,” who could come close to passing the certified welding inspector (CWI) exam.

Selling the Distributor

Some manufacturers’ engineers were so sold on and enthusiastic about their particular products that the distributor couldn’t help but believe in and agree to sell them. Selling the distributor on the product was the first step in increasing sales.

Engineers in the motor generator group explained how their power source was superior to the transformer rectifier power source. It was a constant-voltage power source and much more stable than the rectifier type. Four sets of brushes gave it a smoother arc, and it was said to be more efficient powerwise, once the generator got up to speed.

Of course, the rectifier engineers also had their sales pitch for the distributors. They said the rectifier used much less input power than the generator and made practically no noise. The early selenium rectifiers were touted as being able to “heal themselves” over a period of time, if they overheated.

A Little Rumored Competition

An agreement between a welding equipment manufacturer and a gas supplier was rumored to exist in the 1950s under which the gas supplier supposedly agreed to sell gas and gas equipment only and to stay out of the electric welding equipment business. This company was great at the gas and gas apparatus business, but when the oxyacetylene process became outdated, it couldn’t resist changing. This agreement—if in fact one existed—collapsed when the gas supplier came up with a new process and a machine that we know today as submerged arc welding.

This change created a problem for distributors that handled both companies’ products. Distributor personnel had been trained in-depth to use and sell the gas supplier’s gas and gas apparatus. The welding equipment manufacturer supposedly decided not to make any machines that used gas in any way. Thus, the “innershield” process was born. Distributors did a marvelous job selling this equipment and process. One of the selling points was that it could be used outside without losing the shielding. Gas for the GMAW process would blow away at a wind force of about 5 miles per hour.

The gas/gas apparatus supplier then began producing other electric welding equipment. This did not appear to be a problem for welders, but the factory representatives from both companies perceived the situation differently.

Between a Rock and a Hard Place

In those days producers didn’t sell directly to the end user as they do today. Factory representatives accompanied distributor representatives on sales calls. This served two purposes: One, it was believed that customers perceived they were important enough to merit a visit by a factory representative, and two, distributor representatives learned more about the product.

Problems arose when customers asked questions about the gas supplier’s electric welding product when the welding equipment’s factory representative was present and vice versa. The poor distributor was stuck between a rock and a hard place. “How can I sell ABC’s product when XYZ’s guy standing here is going to say that his product is superior?”

This scenario prompted some detrimental actions by both manufacturers and distributors. The distributor was not happy with the producer’s representative for trying to sell his product when the customer wanted to know about all the products the distributor carried. Consequently, the distributorship owner or manager would call the manufacturer and gripe about its representative offering a negative opinion about a competitor’s product.

The manufacturer, in turn, would say, “OK, we will go directly to the customer (end user).”

War

This began a war between some producers and distributors that still is being fought today. Producers frequently sell directly to end users, especially when a huge job is involved. In the good old days, the distributor rep and his customer became tight friends, and often this friendship lasted for a lifetime.

One of the saddest days in distributorship history was the day that ITW purchased Miller and Hobart. The federal government stepped in and declared that the transactions would constitute a monopoly. Hobart now is limited to building small units; no more large, engine-driven Hobart machines are available. The love affair with these larger machines was killed by the federal government, just as it was for Pontiac and Plymouth lovers.

Figure 4: Author Carl Smith, left, and Bill Rice, former president of Virginia Welding and the American Welding Society.

Gone the Way of the Automobile Dealership

Like the automobile dealerships, most of the original welding supply distributorships have been gobbled up by large corporations. Airgas owns nearly all of the local distributorships in West Virginia and bordering states. Matheson recently purchased a distributorship that had been around for quite a number of years. A few longtime independent distributorships remain. Mabscott Supply is still standing strong in two locations, still owned by the same family that started the business.

The oldest distributorship in the area, Virginia Welding, was sold to Airgas. The president of that distributorship was Bill Rice (Figure 4), the former president of the American Welding Society. Bill’s grandfather, V. S. Rice, started the business as a welding shop. He saw an opportunity to become a distributor and was successful for many years. He also was instrumental in helping other Hobart and Linde distributors get started.

Distributorships now carry several different brands of electric welding equipment and gas apparatus. There is no more “brand selling.” And just as it has with automobile purchases, price has become the most important consideration.

Like the automobile accessory and tire business, much of the expendable market has been taken over by foreign countries. Mexico especially is involved in welding wire, grinding supplies, and safety equipment (prominently leather). Canada plays a large part in manufacturing some welding electrodes and wire, especially nickel.

Airco and the Linde Division of Union Carbide once were leaders in the gas and gas apparatus business. They marketed their own brands of welding supplies and had several distributorships supporting them. Many other brands have gone by the wayside.

At one time both automobile dealerships and welding distributorships had loyalty from and for their customers. With today’s technology and the changing business landscape, customers and distributors no longer know the names of those they deal with. Gone are the good old days when manufacturers and distributors held annual gatherings with food and door prizes for their customers.

About the Author

Professor R. Carlisle "Carl" Smith

Weld Inspection & Consulting

PO Box 841

St. Albans, WV 25177

304-549-5606

About the Publication

subscribe now

The Welder, formerly known as Practical Welding Today, is a showcase of the real people who make the products we use and work with every day. This magazine has served the welding community in North America well for more than 20 years.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Sheffield Forgemasters makes global leap in welding technology

Welding student from Utah to represent the U.S. at WorldSkills 2024

Lincoln Electric announces executive appointments

Engine-driven welding machines include integrated air compressors

ESAB unveils Texas facility renovation

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI