Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Induction key to complex beam rolling job

Shop rolls beams for a unique place of worship--using an unusual process

- By Tim Heston

- July 8, 2011

- Article

- Bending and Forming

The walls of Bob Hardwick’s office are paneled with tongue-and-groove pine. It’s original, carved in 1909 when a metal shop opened for business a few yards away from the railroad tracks running through downtown Birmingham, Ala., at the time a relatively new Southern city.

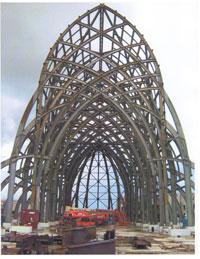

Today the office and a large fabrication facility in Bessemer, just west of Birmingham, house Hardwick Co., a 35-employee structural steel fabricator specializing in bending and rolling of plate, tube, and beams. Though the buildings are old, the shop’s technology isn’t, and a small photo on Hardwick’s pine-paneled wall proves it. The photo shows the construction of the Ave Maria Oratory in a Catholic community near Naples, Fla. The building interior is chock-full of architecturally exposed structural steel, or AESS. The oratory consists of nearly 600 wide-flange beams, all of them formed at Hardwick Co. But these aren’t typical wide-flange beams.

The members were bent the hard way (that is, along the longer axis) to precise radii–plural, because each member was formed to several different radii at different points along their full length. The exposed beams gracefully curve from the base of the oratory to the apex. It’s as if they were forged into these complex forms at the mill. They weren’t, of course, but instead were bent with one unusual machine on Hardwick’s floor.

Allen Hardwick, Bob’s son and chief estimator, pointed to the photo. “Notice that you can’t see any splices [between structural beams]. That’s because they’re not there.”

The Power of Induction

In 2000 Hardwick managers visited a few local machine designers with an idea. They knew pipe had been bent for decades using the heat induction process. So, they asked, why couldn’t such a machine be built to bend not only pipe and tube but also beams and other open structural geometries? They wanted a system that could not only bend tight radii, but also bend shapes to radii infinitely wide, taking advantage of the extreme accuracy and smooth finish that the induction process provided. If a customer needed a piece of architecturally exposed structural steel bent precisely to a 2,000-ft. radius, the Hardwick team wanted a machine that could do it.

The result was a custom machine now at the company’s Bessemer plant. The system—which can handle up to 24-in. wide-flange structural beams, as well as square, rectangular, and round tube—looks unimpressive, at least when comparing it to some of the company’s other machines. Elsewhere in the Bessemer plant are massive Bertsch plate rolls, Roundo angle rolls, a 2,000-ton Cincinnati press brake, and, even more unusual, a 3,000-ton hydraulic press that the company purchased from Chicago Bridge & Iron Co. after it closed its facility near the Birmingham airport. The press stands more than a story tall and sits in a pit 14 feet deep.

The induction bending machine, on the other hand, sits in a 2-ft.-deep pit and comes up to waist level. Beams are fed between two opposing rolls, and a swing arm pulls the workpiece to produce the desired radius. The machine’s small size belies its power, which comes from a copper induction heating tool. Placed just beyond the angle rolls, the tool consists of copper elements that carry heat energy from magnetic induction as well as water or air to quench the workpiece after heating. The area of bending moment, where the forming takes place, is less than an inch wide. The workpiece feeds through slowly, is formed, and then immediately quenched with water or air. The result is a beam or pipe with a smooth, distortion-free arc.

The heat allows the machine to form beams to extraordinarily tight radii. Allen pointed to an arc shape made of rectangular tube about 11 in. wide, 4 in. deep, and about 50 ft. long. The massive structural tube was bent the hard way (along the 11-in. X axis) to a tight radius, then formed the easy way (the 4-in. Y axis) by bumping it on the 2,000-ton press brake, so that the structural tube lipped skyward, a bit like a baseball cap visor flipped up.

“Look,” said Allen, pointing to the surface profile. “No distortion whatsoever.

“We recently rolled 3⁄8-in.-thick 12- by 6-in. structural tube to a 5-ft. radius, the hard way,” Allen continued, “with no deformation.”

The Ave Maria Oratory, built near Naples, Fla., shows what’s possible when wide-flange beams are bent to precise radii. The design may not have been possible without a specialized induction bending process. Image courtesy of Hardwick Co.

Bending 600 Beams

In 2004 Hardwick’s induction process was put to a serious test. Design engineers working on the Naples oratory called on Cives Steel Co., a structural fabricator with plants nationwide. The oratory’s bold design involved repeating arc shapes that curved up toward a central apex.

The engineer first made a design of structural tube, but that idea was nixed. Karl Hanson, manager of production and purchasing at Cives’ Thomasville, Ga., facility, recalled that such tube couldn’t be found or made, at least for a reasonable price. At this point the team considered an alternative: Why not structural beams? That’s when Hardwick Co. entered the picture.

The oratory, a complex web of curved beams formed to multiple radii, presented a serious fabricating challenge. The beams start at one radius and then at certain points transition to another radius, then another radius, another, and so forth, as the beam shape arcs upward.

“Sometimes the radius was even reversed,” Hanson explained. “The beam would arc one way and then, by the end, it would arc the other direction. It looks like an ‘S.’”

That’s easy enough to draw on a computer, but to actually form those beams took careful planning. Each beam had to be free of any distortion. The oratory design is symmetrical; the left side mirrors the right. This meant that opposite beams also had to mirror each other, so that they would meet at the apex. “If these beams weren’t formed precisely, they just wouldn’t match up,” said Hanson. “You just can’t get that kind of accuracy without using heat induction.”

The beams also had to be formed precisely so they would cross various bisecting beams at just the right spot. The entire structure has no internal supports. “All of these shapes carried loads,” Hanson explained. “So where one beam intersected and continued on the other side, those points had to match up exactly; otherwise, the loads wouldn’t be transferred. And if the loads weren’t transferred, the members would collapse.”

The process is no speed demon. The structural beams inch through, little by little, through the copper induction tool. Unlike cold rolling, the induction bending process takes place in one pass, so there’s no room for error. “We knew it would be a slow process,” Allen said, especially for beams requiring tight radii. After all, some wide-flange beams were formed at 208 pounds per foot to a 25-ft. radius—again, the hard way. “But the benefit of the product quality more than outweighed how long it took to roll the beams.”

Enabling Technology

The project finished smoothly and on schedule, thanks in large part to the unusual beam forming process at Hardwick Co. Allen emphasized that, though the induction machine can produce product of extremely high quality, it’s not the answer for everything. After all, “cold rolling really built this company,” Allen said.

Still, the induction technology gave Hardwick a rare fabrication capability, and without it, the extraordinary design of the Ave Maria Oratory wouldn’t have been possible.

Small Shop, Nationwide Reach

Gene Wilson, a 53-year Hardwick Co. veteran, has stories to tell. He’s not a blood relation to the Hardwicks, but he might as well be. Jim Hardwick—“Papa Jim,” as Wilson called him—hired him when he was only 16, and since then he’s worked his way up to be part owner with members of the Hardwick family.

“The business was started in 1909,” Bob Hardwick, company president, explained. “My grandfather bought the business in the 1920s, and my father [Jim Hardwick] took it over in 1949. After school I came back here, and Gene Wilson and I bought the business, along with my brothers Jay and David, in 1976.”

As a teenager working at Hardwick in the 1950s, Wilson recalled eight individuals arriving at the company’s Birmingham plant from the government’s new research center in Huntsville, Ala.—today’s Marshall Space Flight Center. They arrived with a special, proprietary plate material that needed to be cone-rolled. “A few of the men had brooms and dustpans,” he said. “They didn’t leave any [metal] dust behind. It must have been a special material that they didn’t want anyone to get a hold of.” As it turned out, those cones formed the shell of space capsules used in the Mercury space program.

Wilson and the three Hardwick brothers, along with Bob’s son Allen (now chief estimator) have managed a shop that has had nationwide reach, mainly due to the structural fabricator’s unusual capabilities. This includes spiral forming. The 36-in., wide-flange beams for the grand spiral staircase in the foyer of Hollywood’s Kodak Theatre—home of the Academy Awards—were formed by the people at Hardwick. Using multiple cranes in front of and behind the press brake, the bending team formed the massive spiral, bump by bump, until the beams were spiraled to within tolerance.

Wilson chuckled. “People in Hollywood couldn’t believe that the only shop they could find to do the job was a small company in Alabama.”

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Hypertherm Associates implements Rapyuta Robotics AMRs in warehouse

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI