- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Everything you need to know about flatteners and levelers for coil processing—Part 1

How flat-rolled metal gets unflat

- By Eric Theis

- October 10, 2002

- Article

- Bending and Forming

|

Does your coil processing operation preserve or improve quality? Do you struggle just to keep the quality the mills put into their flat-rolled products, or do you have equipment that can upgrade quality and add further value to your coil processing operations?

To maintain material quality, first we must understand flat-rolled metal defects and how people and processes can cause them.

Types of Shape Defects

Three categories of flat-rolled shape defect exist, and resolving each requires a different approach and equipment configuration. In ascending order of complexity, the three categories are:

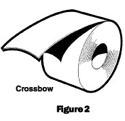

1. Surface-to-surface length differential. This includes coil set (see Figure 1) and crossbow (see Figure 2), which are related problems.

|

| Coil set is a type of surface-to-surface length differential defect. |

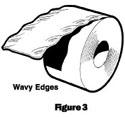

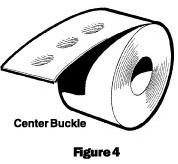

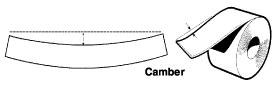

2. Edge-to-edge length differential. If the edges are longer than the center, you will have wavy edges (see Figure 3). If the center is longer than the edges, you will have center buckle (see Figure 4), sometimes called oil can or canoe. This category of defect also includes camber (see Figure 5) and twist (see Figure 6).

Edge wave, buckles, and camber are easy to understand. Twist is a little more difficult to visualize as an edge-to-edge length differential issue. If we unwind a twisted strip, we'll see that the edges and center have different lengths, depending on the geometry of the twist, or helix. Twist is not simply coil set up on one side and down on the other side. A twisted strip has a side-to-center-to-side length differential that, unlike edge wave, continues all the way across the strip.

3. Surface-to-surface thickness differential, or crown (see Figure 7). This is a common problem for slitters, and it will be discussed in Part IV of this article. Flatteners or levelers can't reduce crown significantly because their work rolls are offset. It takes a rolling mill with opposed rolls to do that. This article discusses the causes of crown, but not how to eliminate it.

|

| Crossbow is another type of surface-to-surface length differential defect and is related to coil set. |

Sources of Shape Defects

The mills have come a long way in the last few years in controlling shape and thickness, but perfection is difficult. You need to understand this--not because you're going to be in the rolling mill business, but because you must be realistic when talking to the mills about your expectations for product quality.

The producer mills would like to make crown-free flat-rolled coils every time if they could. If they miss that goal, they much prefer a thicker center for tracking purposes, so the coil runs straight through the mill stands. If the edges are thicker than the center, the coil won't go straight.

|

| Wavy edges are an edge-to-edge length differential defect and are created if the edges are longer than the center. |

At the Hot Mill

At the hot mill the crown or thickness profile can be changed without changing the shape or flatness, and vice versa.

Hot mills try to get the relationship between crown or profile and shape, but achieving both perfect shape and perfect crown control is almost impossible. With new automatic gauge control (AGC) technology, the mills are doing much better, but perfection remains an elusive goal.

At the Cold Mill

At the cold mill, every time we change the thickness profile, we also change the flatness. The cold mill roll gap should start out being set to the same profile as the crown of the incoming hot mill product. Then, as the cold mill gap is adjusted to reduce the crown, the coil also will come out flat--if the hot mill got the relationship between crown and flatness right to begin with.

If the cold mill rolls or hot mill coils have too much crown, the mills will roll out the center, creating center buckle in the process (see Figure 8).

|

| Center buckle, another type of edge-to-edge length differential defect, is created when the center is longer than the edges. |

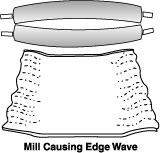

If the cold mill rolls or hot mill coils have too little crown, the mills will roll out the edges and create edge wave (see Figure 9). This is fairly common in mill master coils.

Mill work rolls and backup rolls bend and compress under the vertical loads it takes to reduce plate or sheet coil thickness. In theory, if the work roll surfaces were absolutely parallel, the top and bottom surfaces of the rolled product would be parallel--no crown. But the fact is that everything is deflecting under the rolling loads and so it doesn't work that way.

The mills deliberately crown their work rolls slightly larger in the center to allow for deflection and compression under load. The amount of roll crown that is added is a compromise, a best guess. In addition, mills can control the gap profile by bending these huge rolls or by expanding them with hydraulic pressure like a huge steel balloon.

|

| Figure 5 Camber is an edge-to-edge length differential defect. |

You've probably seen the pictures of the mill control pulpit with all its controls and computer monitors. Every time the operator pulls a lever, he changes what's going on at that mill stand and, therefore, the amounts of deflection.

The hot mill's strategy is to get the relationship between crown and shape correct so that they will both come out right in cold rolling. If that sounds difficult, it is!

The tension on the coil strand through the mill also affects the thickness reduction at the mill roll. It shouldn't surprise us then if that the heads and tails of the mill coil are thicker than the middle because they did not have full tension.

Problems Aren't Only in the Mills

Do you remember Pogo? Pogo was a small opossum and a great philosopher--in the Sunday newspaper comics! He once said, "We have met the enemy and they is us!" Well, sometimes we are our own enemy--because shape defects can be induced at any stage in processing of the coil, and we're all part of that.

|

| Twist also is an edge-to-edge length differential defect. |

How many metal buyers would like to specify coils without coil set? The problem is that coils are in coil form. Most coils have a 20- to 24- inch ID. In most cases, unless the metal is very thin or very hard, coil processors put coil set back into the material during the recoiling process. The producer mill's leveling equipment can make the material dead flat, but then the metal is recoiled for shipment to you, and that puts coil set back into it.

Where does coil set come from? It's in the coil!

Coil set should be more pronounced on the coil's inside wraps and less on the outside because the inside bend radius is smaller. In fact, it's possible to have residual reverse coil set in the outer wraps from the original master coil before it was swapped head to tail in some previous operation. We also can induce reverse coil set during our own uncoiling process by backbreaking the material over a small breaker or passline roll.

How many coil processors can use a 60,000-pound master coil straight from the rolling mill? Somebody has to pickle it, anneal it, coat it, slit it, and perhaps cut it to a smaller OD. Flatness problems can arise anywhere along the line. Here are some examples of how this can happen.

|

| Crown is a surface-to-surface thickness differential defect that is a common problem for slitters. Flatteners or levelers can't reduce crown significantly because their work rolls are offset. |

I once inspected a brand-new steel mill tension leveler in a hot-dip galvanizing line. The metal coming out of the zinc pot and going into the leveler looked terrible. It was like a bright, shiny mirror coming out of the tension leveler. Then it went into a 40-year-old, misaligned accumulator before being rewound or sheared to length for customers. The accumulator destroyed the shape quality. The shipped coils and sheets were not flat. The line operators were frustrated because they knew about the problem but could do nothing to resolve it. My heart went out to them.

I watched an aluminum mill tension leveling coil on a new line. It was dead flat coming out of the leveler and then they recoiled it, under a lot of tension. The coil was crowned, meaning that the center of the strip was thicker, so the center of the coil on the rewind arbor had a larger OD. Big surprise! The operators were rewinding the coil over a barrel. That was pulling center buckle back into it!

Flatness inspection had been done after leveling and before rewinding. QC insisted the material was dead flat. The customer said it was buckled when he unwound it. Engineering wanted to know about the material's "memory" or trapped stresses. Everyone was wrong.

|

| Figure 8 If the cold mill rolls or hot mill coils happen to have too much crown, the cold mill will roll out the center and create center buckle. |

I was asked to provide operator training on an old roller leveler that had been very badly overloaded. The service center owner told me that the work rolls had just been reground and the machine recalibrated. His men still could not get flat material out of it.

We found that the backup roller pins were badly distorted and bent. The side frames were sprung. No amount of training was going to help them. Worse yet, the line management personnel didn't understand that they were the culprits.

Some years ago I watched a badly maintained service center slitter producing "snakes." The recoiler arbor had been bent and was wobbling several inches as it rotated, pulling an oscillating camber into each slit mult coming from the tensioning device.

Any rolls in the system, such as pinch rolls, slitter arbors, flattener rolls, leveler rolls, and, of course, feeder rolls, that deflect or that are misaligned can produce edge wave or even camber. These rolls can put uneven pressure on part of the material and destroy the coil shape in the process.

|

| Figure 9 If cold mill rolls or hot mill have too little crown, the cold mill will roll out the edges and create edge wave. |

It's surprising how many operations do not perform preventive maintenance or calibration and realignment. "If it ain't broke, don't fix it." Right!

It's surprising how many times I've found that flattener and leveler rolls haven't been reground or recalibrated in years, if ever.It's surprising how many line operators don't have access to information about machine capacities or to either nominal or actual material yield strengths of the metals they are processing.

It's surprising how many line operators have had no training on the meanings of these critical numbers.

It doesn't make sense to talk about equipment upgrades if the people running the equipment don't understand the equipment they use now. Before we start talking about new equipment, let's see what we can do to get the best out of what we already have. I'll discuss this in Parts II and III of this article series.

Remember, we need to make good stuff out of the bad stuff. Not the other way around.

About the Author

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI