Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Keeping up with the Joneses

The history of Jones Metal Products comes full circle

- By Tim Heston

- June 13, 2012

- Article

- Shop Management

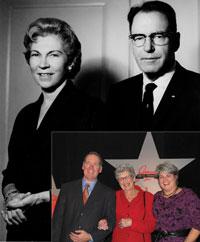

Figure 1: Jones Metal Products has a rich history, beginning with Mildred and Cecil Jones (left). Last year their daughter Marcia Jones Richards (Inset, in red) sold her shares and passed on the business to the next generation. This included her son David, the company’s purchasing manager, and daughter Sarah, now CEO. (Not pictured is Marcia’s daughter and board member Jessica Richards-Palmquist.)

In 2004 Marcia Richards was at a crossroads in life (see Figure 1). Her husband had died, and she had a metal fabrication business in her name. Should she grow the business and pass it on to the next generation, or sell it?

The business, Jones Metal Products, came from her side of the family. Years before, Cecil Jones, her father, ran Kato Engineering, a Mankato, Minn., company that developed and manufactured electrical generators and numerous other products. By 1942 Kato needed a reliable sheet metal supplier, and so the family launched a business dedicated to metal fabrication and installation: Jones Sheet Metal and Roofing Co.

Marcia thought about her grandmother, Lulu Barnes Page, who in North Mankato ran a bakery/café, owned and ran a rooming house, and raised six daughters while her husband worked for the railroad. Mildred, the fifth daughter, went to school for medical technology and worked as a medical technician for several years. During the early years of the Great Depression, both Cecil and Mildred kept their marriage secret because they both had full-time jobs, which was taboo in those days.

She thought about her family’s drive to compete in business. One morning decades ago Cecil arrived to work at Kato Engineering to find two customers in his office, both presidents of FORTUNE 100™ firms. These firms bought various parts from Kato, but they also made light plants (light sources powered by portable generators), which happened to compete with light plants Kato made and sold directly. When the two corporate titans threatened to pull their business if Kato Engineering didn’t stop making competing products, Cecil obliged.

True to his word, Cecil made sure Kato Engineering no longer produced light plants, which meant the company kept its lucrative contracts with those FORTUNE 100 firms. But, curiously, his light plant product didn’t disappear from the market. Cecil asked his brother-in-law if he’d like to launch a new business to produce certain light plant designs—products that coincidentally looked strikingly similar to the ones Kato stopped producing. This led to yet another family business, Katolight Corp.

Such entrepreneurialism and tenacity helped shape the family legacy, and this no doubt helped solve Marcia’s dilemma in 2004: Should she hold Jones Metal or sell it? The other two businesses had since left the family’s hands. Katolight Corp. today does business as MTU Onsite Energy; Kato Engineering now is a division of Emerson Industrial Automation. But Jones Metal had remained in the family.

And there it remains today.

“She wanted to hold the company and pass as much as she could to the next generation.”

That was the next generation talking—Sarah Richards, Marcia’s daughter and current CEO of Jones Metal Products.

Marcia made her decision during a transitional time at Jones. Employees and managers had begun to rethink the way they worked. Decades before the shop’s experienced fabricators had shepherded projects from beginning to end: cutting the sheet and plate, bending or rolling, welding, and grinding it; and then delivering and often installing the fabrications on-site.

Figure 4: To manage part flow, personnel schedule many jobs based on the capacity of the company’s welding department.

Those manual processes are long gone, but in recent years employees began thinking like those early fabricators. Instead of concentrating on machine uptime and combining batches for fewer machine setups, they focused on the most effective way to produce and ship a job. In this sense, what was old became new again.

Got a Light?

Jones Metal wouldn’t exist without Kato Engineering, and Kato wouldn’t be what it is today without Cecil Jones. He invented a system that converted the power from DC storage batteries for AC appliances, and in 1928 he met with the founders of the then fledgling Kato Engineering. They realized his invention’s enormous market potential and quickly brought the young electrical engineer onboard. The original owners eventually left the firm (the story goes that one left unannounced and essentially forfeited his shares), and by 1936 Cecil owned the company outright.

Before and during the war years, Kato kept winning contracts for more generators, including some for the original 31 U.S. Army airfields. At one point the company was manufacturing thousands of AC generators not only for the U.S. military, but also for nations abroad.

“The big push in the 1940s was the war effort, obviously, and providing equipment for the battlefield,” said David Richards, Marcia’s son and the fabricator’s current purchasing manager. “The destruction of infrastructure created a need to provide portable sourcing [of power].”

Even after the war, demand for portable electrical power continued unabated, especially for light plants (see Figure 2). “Today, if you want to power a barn, you run wire to it. But in the 1950s, you didn’t do that.” Wiring every barn and shed could get expensive, “so if you wanted a source of electricity, you bought a light plant. You could move it from barn to barn,” David said.

By the 1940s Kato Engineering employed almost 500 people who fulfilled thousands of orders. The company needed to expand its metal fabrication; doing it all in-house just wasn’t cost-effective. And so in 1942 the family launched its own sheet metal venture, Jones Sheet Metal and Roofing Co. The business was launched in Mildred Jones’ name, not only for tax reasons but also because, as Sarah explained, “she appreciated and enjoyed working and having income. She also was an independent, strong-willed woman.” Mildred sat on the company board for more than 50 years.

The Old Way Becomes New

In the early 1950s the business changed its name to simply Jones Metal Products. By then the business was acting less like a division of Kato Engineering and more like a full-service, custom metal fabricator. And evidence for those early jobs can be found all over Mankato.

Historically, the town has been a center for food processing. Local flour milling and soybean processing plants needed someone to make massive end caps for processing equipment, and Jones Metal workers obliged, spinning the sheet on massive lathes—all manual, of course. Hand brakes abounded, as did three-roll plate rolls. The company’s photo collection shows the metal fabrication of a bygone era (see Figure 3).

For decades multitalented fabricators saw jobs through design, engineering, manufacturing, and delivery. And if there were no machine that could fabricate sheet metal a certain way, they would build a machine that could. But over the years jobs became more narrowly defined. Each person focused on how to get the most out of the punch press, laser, and other machine tools. During the early days of NC and CNC, this made sense. Machine setup was tedious, the nesting manual. If fabricators didn’t group like jobs together to reduce setup times, those expensive machines could sit idle for long periods, waiting to be fed part programs.

Manufacturing technology changed over the decades, changeovers became easier, programming automated. Still, personnel began to realize that their manufacturing methodologies didn’t necessarily change to match the technology. By the 1990s schedulers looked out 40 days or even more to group similar parts in nests, to minimize those dreaded changeovers. In reality, the shop was continually cutting parts that weren’t needed immediately, which meant Jones was spending a lot of cash on inventory, not to mention excess movement digging through mounds of work-in-process.

Figure 5: Jones has two welding robot cells. One handles a specific part, while the other, thanks to flexible tooling, handles numerous jobs.

“It got to the point where we cut parts, and we’d be on the 39th sheet of a particular run, and a customer would expedite a certain part,” David said. “We actually would just cut the part again, because we couldn’t dig through all the cut parts fast enough. How lean is that?”

The Flow of Value

Several years ago company managers set out to change the situation. Besides implementing internal improvement programs, the company also reached out to local organizations like Enterprise Minnesota (www.enterpriseminnesota.org), which offered a grant-funded lean training program connected with the University of Minnesota.

Today personnel schedule many parts based on the capacity of the company’s welding department, which has 35 welders and two robots (see Figures 4 and 5). And regardless of capacity and machine loads, if a part doesn’t need to be cut within the next three to five days, it’s not programmed onto a nested sheet.

Jones invested in new laser cutting systems that change nozzles and gases automatically. The machines can process sheets of different material grades and thicknesses sequentially, producing kits of parts needed immediately for downstream bending, welding, and assembly. Employees documented procedures for moving material and installed conveyors near press brakes so that material blanks could flow quickly from cutting and flat-part deburring to bending.

Jones also initiated a major 5S program in a department that performs rolling as well as various secondary, hands-on operations like spot welding, drilling and tapping, and some machining. This department handles myriad parts and numerous short runs, so arranging tools to speed changeovers was critical.

Freeing the Bottlenecks

Part volumes at Jones range from one-off prototypes to about 500, much of it repeatedly ordered throughout the year, though part designs may be modified periodically. Minus outside operations, on average it takes only three days for a part to work its way through the entire shop floor.

Of course, manufacturing time depends on part complexity and order size. A simple flat part may take a day, while a complex subassembly may take a few weeks, even with little lag time between work centers. This makes Jones’ operation highly variable, an unavoidable fact of life in the high-mix, low-volume world. A work center can be overwhelmed one day and slow the next, depending on the mix of orders on the floor.

Maintaining predictable manufacturing times requires consistent part flow. To this end, Jones employees focused on freeing the bottlenecks, and this included the part break-out area where operators offloaded laser-cut parts. Producing only what was needed immediately on the laser helped reduce the bottleneck. Managers then increased capacity by hiring a few more people and moving workers in and out of the part break-out area as needed.

Improvement projects have progressed to the press brake area, where personnel are working to perfect placement of conveyors for optimal part flow. They also want to increase capacity with more machine operators and, eventually, more machines.

“It’s about continuous flow,” said David. “Don’t stop a product from front to back. It’s like leveling a coil of steel. You never want to stop it, because you’re going to put a coil break in it or a roller mark in it.”

Figure 6: Jones Metal recently invested in new laser cutting centers, and managers hope to use this increased cutting capacity to grow the flat-part-cutting business.

Freeing Capacity for the Upturn

All these improvements increased capacity at a good time. Business declined in 2009 with the rest of the economy, but between 2010 and 2011, the 150-person company experienced 30 percent growth in sales, thanks in large part to new military work. Managers expect sales to grow another 7 percent this year, to just shy of $23 million.

The customer mix—agriculture, power generation, military, heavy construction equipment, and others—reflects the company’s new approach to manufacturing. Nowadays the fabricator receives more requests for quotes for complex assemblies, and often it is asked to collaborate with customers during early product development.

In other words, it’s no longer just about fabricating piece parts. As Operations Manager Rikk Schaehrer put it, “Our saying has been, ‘A design on a napkin to your door.’”

Employees may not carry a part through production like fabricators did in the 1940s, but like before, employees are cross-trained on multiple processes, so they can move where needed to maintain part flow.

Shop workers also visit customer plants, where they can see how the products they fabricate fit into larger assemblies.

As Sarah explained, this gives them “that GE television commercial moment,” where employees watch an engine they built lift a 747 off the runway. More important, she said, customer visits also return employees’ focus to how a quality part fits into a larger assembly. It’s no longer about how fast a laser cuts, a press brake bends, or a welder welds. It’s how Jones can quickly deliver a better part, time after time, and make life easier for the customer.

Preparing for Smooth Part Flow

It may take only a few days for a product to flow through the shop, but when the company receives a purchase order for a new part, Jones’ design engineers may spend several weeks with the customer, perfecting manufacturability. Does a part need this much welding? Could other operations like bending reduce the number of weld inches? Could an additional bend eliminate a weld entirely?

Jones now wants to make this process more efficient. “We’re in the discovery phase. We’re mapping out our support processes for all of our major customers,” Sarah said. “And then we’ll take those maps and create a smoother future-state map. When we release jobs to the production team, we want them to be perfect, so that they flow through production without stopping.”

The company is on a quest to shorten the overarching cycle that can make or break a contract metal fabrication business: the order-to-cash cycle. Shortening it naturally increases shop capacity, and shop managers have been aggressively marketing that open capacity.

The company attributes at least 10 percent of sales to new accounts over the past five years. It also has invested in several large-bed lasers and plans to market this new capability to companies that need quick turnarounds for flat parts (see Figure 6).

Like so many manufacturers, Jones Metal continues to have trouble finding qualified machinists and welders.

“Still, we can do all we can on the sales end,” said Schaehrer. “But to affect that bottom line, my group is responsible for throughput and waste reduction. We are going to be looking at all of our processes to figure out how we can become more efficient. We are projecting a 10 percent improvement in contribution margin in 2012.”

Coming Full Circle

A promotional photo showing a family enjoying an afternoon on a pontoon boat captures that quintessential, wholesome goodness of the 1950s family on vacation. But a close look at the pontoons reveals how metal fabrication expertise can change a product (see Figure 7).

“As I have been told, the pontoons for Kayot at one time had blunt ends, making the craft a bit clumsy in the water,” Sarah said. “So the design group and fabrication specialists at Jones came up with and patented the tapered cone.” Each pontoon used to comprise five pieces, meaning that each pontoon assembly required five weld seams. Jones developed a custom, hydraulic machine that formed the pontoon out of one piece. What previously was five pieces became just one, with only one weld seam.

That kind of thinking, she added, exemplifies the design-for-manufacturability work employees perform today. “When I talk about employees seeing flow of value to the customer, and making sure they fix that flow before it breaks down so the customer doesn’t feel a thing, I think that’s very similar to the individual fabricator [in the 1940s and 1950s] who would go meet the customer, help create the design, come back and manufacture the product, then deliver and install it.

“That was the model back in 1942, and you could say that we’re trying to create that same feeling again now.”

Right Skills Now, in Mankato

Since 2010 Mankato, Minn.-based Jones Metal Products has been in growth mode. Starting late that year and into 2011, the fabricator kept hiring when other shops weren’t.

Now that other shops finally have started hiring, Jones’ appetite for new talent hasn’t abated, and this has exacerbated a perennial problem: finding skilled people. “When the economy was down, we could find welders and machinists. Now it’s hurting our growth. So many companies are hiring,” explained Rikk Schaehrer, operations manager.

Later this year the company hopes to work with local schools on a mentoring program launched by the federal government’s Right Skills Now (rightskillsnow.org) initiative. The fabricator plans to provide internships for students working their way through the accelerated jobs training program. Nearby South Central College in Mankato already has a Right Skills Now machining program, and a welding program is in development. Jones Metal hopes to benefit from both.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI