Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Lights, camera, lean--recording manufacturing efficiency

Automotive supplier refines its lean manufacturing approach with sports video technology

- By Tim Heston

- July 30, 2010

- Article

- Shop Management

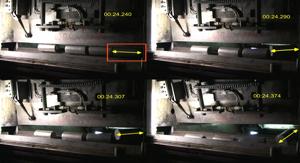

Figure 1: Nexteer Automotive has borrowed video technology from the sporting world to analyze any shop floor movement—be it by a human, manufactured part, or machine. Like the consecutive motions of a figure skater, this view shows a frame-by-frame analysis of a part being misloaded into a machine.

Dave Westphal exudes the unwavering enthusiasm of a proud father. Without such gusto, perhaps a multibillion-dollar automotive supplier wouldn’t be where it is today.

The former welding engineer and Ferris State University grad can spout figure skating jargon like a regular Dick Button. You can tell he just beams when his 13-year-old daughter, a competitive skater, nails a jump. “Just think about skaters hitting a jump at 15 or 18 miles an hour [and performing] three revolutions,” said Westphal, still beaming. “The odds of knowing exactly where their hands need to be, without actually seeing it for themselves, are next to zero.”

This, he said, is why for years topnotch skaters have used digital video to study every move during this Lutz or that double Axel. Such technology has allowed various athletes—skaters, swimmers, golfers, or any competitor for whom precision movements matter, really—to view exactly what move caused what error and which moves lead to the greatest success.

While watching his daughter skate, Westphal had an epiphany. When you get right down to it, manufacturing is about precision movements too.

New Name, Old Organization

Westphal is director of global lean manufacturing for Nexteer Automotive, a $2 billion automotive supplier of steering and front-axle components, with 22 plants worldwide. The Nexteer name is new, but the Saginaw, Mich.-based organization isn’t. Roots go back to General Motors, which spun the group off to become part of Delphi in the 1990s. Then last year the company became a direct subsidiary of GM. At this writing, GM had agreed to sell the unit to China’s Pacific Century Motors, a joint entity between an investing arm of the Beijing municipal government, and Tempo, a Chinese automotive components supplier. The deal is expected to close by the end of the year.

No doubt, the automotive marketplace hasn’t been for the easily distracted of late, but throughout the business deals, Westphal has focused on operations. Like his daughter’s passion for precision skating, Westphal has a passion for the precise, efficient moves of humans and machines on the plant floor. And today both daughter and father use the same technology to perfect their craft.

The Benefits of Video

Several years ago Nexteer paid a few thousand for that software technology, called Dartfish. As Westphal explained, for a company accustomed to purchasing and maintaining massive stamping presses, hydroforming equipment, robotic welding cells, and other machines, the investment was really a drop in the bucket.

The software essentially allows Nexteer to track any video-recorded point through time and space (see Figure 1). For instance, it can track an operator’s motion through a stamping cell. “I can tell the software to follow the sticker [placed near an operator’s hand], so I can track everywhere a person’s hand goes as it feeds material into a machine,” explained Westphal. Often a person might use one hand almost all of the time, while using the other hand only 20 percent of the time. By balancing hand utilization, he said, the company has improved cycle times by 20 to 40 percent.

Managers approached the video technology like any other continuous improvement tool. It’s not used for discipline. Nexteer, a United Auto Workers shop, has a good relationship with the UAW in Saginaw, and the union participated in Dartfish training before the tool was employed several years ago.

“Upfront communication really is key,” Westphal said.

Figure 2: Dartfish software, which requires a Windows laptop and digital video camera, is used to analyze one of Nexteer’s machining processes.

Old Concept, New Technology

Video-recording the shop floor isn’t new. Almost 40 years ago, in fact, The FABRICATOR (then published in newspaper format) ran a front-page story about a Kansas manufacturer, Hesston Corp., that videotaped the motions of operators. The practice was a bit more arduous back then, and nothing was digital. But the basic idea was similar:

“The method consists of filming the worker on the job with a compact videotape unit and playing back that film while he and his supervisor watch. This method eliminates the ‘Here’s what you’re doing wrong’ approach and, instead, allows the employee and supervisor to view together what a third, unbiased entity—the camera—sees.”

That prose was first printed in 1971, but it’s just as applicable today. Only now companies have better tools. Digital cameras cost a few hundred dollars, and software allows for real-time measurement of all motions on the floor. Low lighting usually doesn’t present problems either.

“We can grab anything we’re doing, from the path of a part in production to the human aspect of it, and feed that video immediately back to a laptop on the shop floor,” Westphal explained (see Figure 2).

Ever see ESPN or NBC Sports overlay athletes—say, two downhill skiers—one beside the other? The lean manufacturing team at Nexteer has done something similar. For instance, one machine operator may consistently process more parts better and faster than others. In this case, Westphal’s team would set up a tripod near a cell and record various operators, and then overlay one operator over another to compare how each person moves about the workcell. The result may reveal that efficient workers touch or load components completely differently than other operators.

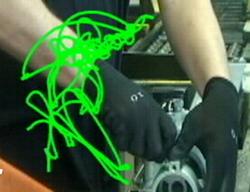

The team considers both worker ergonomics and efficiency (see Figure 3). The goal is to make each move more comfortable for the worker; in turn, greater comfort usually leads to greater productivity. “If we see the operator go through 15 back-and-forth motions with his hands, our goal may be to reduce that to seven. When we cut those motions in half, the cycle times drop accordingly. So instead of the operator turning around and reaching for a sheet on a cart, we may move the palm button and redesign the cart so that the sheet can slide right off into the press.”

When designing cells, shop managers have used video to track people’s walking paths and hand motions. An operator’s right hand, the one holding a part, may be closest to the cycle initiation switch; the video would show how the worker switches the part to another hand for every cycle. In this case, the company may redesign the lean workcell so that the operator can access the switch with the left hand—and all this is determined before the cell is put into production.

Redesigning the cell in such a way may save only a few seconds per cycle, but over time those seconds add up to significant savings. “We live and die on cycle times that are less than 20 seconds,” Westphal added. “So for us, saving just a few seconds per cycle can be huge over the course of a full day.”

Variables don’t have to include human motion. The video technology can record any point in space and track how it moves over a period of time. “For instance, I can see how one stamping press may be cycling,” he said. For example, let’s say something goes wrong every fifth hit in a progressive die at a certain station. “So I focus the video on that station, run the press for a period of time, and then review the video and slow it down. We can often slow it down to a point where we actually can see a defect being formed, due to an escapement not working, certain mechanical failures, or anything else.”

Immediate Correction

Westphal has worked for the organization—first GM, then Dephi, and finally Nexteer—for 20 years. He started as a tool- and diemaker, got an engineering degree, and returned to take on various manufacturing operations and leadership roles. He was trained in lean manufacturing predominantly by Toyota sensei, including Tom Harada, who spent 35 years with Toyota. During some of those years, Harada spent time at the Kamigo engine plant under then plant manager Taiichi Ohno, today considered the father of the Toyota Production System.

Figure 3: Nexteer uses insight revealed from spaghetti charts to improve cycle times by up to 40 percent. Here, every wrist movement and deviation is captured in one shot.

Considering his background, no wonder Westphal has embraced video recording’s potential when it comes to lean manufacturing. It has made easier one of the most challenging aspects of any lean implementation: identifying waste. Workers don’t purposefully work inefficiently. It’s identifying waste—including wasted motion—that can be an uphill battle. This is where video helps. When skaters see their hands or legs move a certain way, they correct it easily. The same goes for manufacturing workers.

“We often bring a work team into a room and show them the video,” Westphal said. “Almost all of them usually view the video and say, ‘I didn’t know I was doing that!’ And the correction is immediate.”

Designing out the danger

Nexteer Automotive experienced some safety issues when it came to one metal cutting operation. Some workers received lacerations after pulling a razor-sharp chip off the tool. Of course, workers were told to use caution and wear personal protective equipment where applicable, but safety managers knew that the best approach almost always involves preventing the hazard from occurring in the first place.

This was where David Westphal, director, global lean manufacturing, and his team came in with a video camera. They connected to a laptop using Dartfish software, recorded the operation, and dissected the video.

“We could slow the video down to the point where we actually could see that chip forming at the end of the tool,” Westphal explained. “We were able to match up that data with the machine G code. We put in a few hesitations, changing the feeds and speeds, and we ended up dropping the [cutting tool] rake angle a little bit.” This formed the chip differently, which prevented the hazard. “The result was we went from multiple lacerations during a time period to zero.”

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI