Contributing editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

10 burning questions you asked about the steel price meltdown

The answers you want to know

- By Kate Bachman

- May 4, 2004

- Article

- Metals/Materials

|

My dad is fond of saying that when he was in the Army, he was trained not to question orders. "Mine was not to reason why," he'd say. "When my sergeant said 'jump,' I asked 'How high and how far?'" Today metal fabricators trying to ride out the storm are asking not only "How high and how far?" but also "Why?" The following questions have been posed directly by you, and The FABRICATOR relayed your questions to those involved and those observing this steel tempest.

1. What is the cause for the current spike in steel prices, and why is the spike so sharp?

Chris Plummer, managing director, Metal Strategies: The most important factor is China. Around early 2002 the Chinese government instituted a policy of very strong growth, mandating public works projects and freeing up some of the banking regulations to help promote and finance new construction and industrial projects. Basically, they put their economy on full throttle, and that has had an overwhelming effect on any commodity that you can think of, from steel to aluminum to raw material to consumer goods. It has even had an effect on things like ocean shipping rates.

At the same time the Russians, Ukrainians, and some of the other major exporters of scrap—and by the way, the U.S. has always been the world's largest scrap exporter—over the last 12 months have instituted significant tariffs or outright bans on exports of scrap, as well as limitations on alternative irons, such as pig iron and direct-reduced iron. And there hasn't been much in the way of new, alternative iron capacity built in the last several years, so that constraint on the flow of material coming out of Eastern Europe has been the ultimate catalyst for pushing the price up. It's a chain reaction. The magnitude has even shocked the Chinese as much as the rest of the world.

Wayne Atwell, managing director, Morgan Stanley>:China's steel consumption has grown much faster than anticipated and has put a strain on the global raw material industry. High freight rates have driven up the cost of moving iron ore and coal to Europe and Asia from Brazil, South Africa, and Australia. This has driven up the cost of raw materials in the U.S.

|

China historically has been a source of low-priced coke. The rapid growth in China's steel industry has forced the Chinese to cut back coke exports. The increased demand for coke has put pressure on the met coal market. A fire at a U.S. met coal mine has caused a shortage of domestic coke.

Charles Belanger, manager of marketing strategy development, Ispat Inland Inc.: Sometime in the late '70s China decided to move from what I like to characterize as an economy equivalent to ours [U.S.] in the 1850s to 2010—by 2010. This is one-sixth of the

Look at China's growth in steel consumption, and then look at everybody else. The rest of us are pretty flat, because our infrastructures are largely in place. When you're going through industrialization—we're talking about roads, pipelines, electricity transmission lines, sewer systems, dams, light poles—we're talking about fairly intense per-capita steel use. Japan, Germany, and South Korea are the models they are following, but in each case their mass was not critical enough to create the upset, the perfect storm that we're looking at right now.

So what did happen in January? Obviously, there were forces in play that suddenly became manifest when you stress the situation. You just put stress on what I refer to as fault lines developing for over 20 years. The reason the tip didn't happen sooner is that Europe and the U.S. were going through recessions. The fact that they [Chinese] were increasing their demand and consumption of steel was offset by the fact that the rest of us were going to sleep. If it weren't for the Iraq War, we would have seen this a year earlier, because the demand in the U.S. would have gone to that tipping point.

Something not quite so obvious is starting to turn up on the radar screen—there isn't enough shipping out there to manage the level of demand that's going on out there. That is the other fault line.

|

Scrap is the feedstock [85 to 90 percent] for electric arc furnaces [EAF] for mini-mills. What you may not know is from 5 to 30 percent of the feedstock for a basic oxygen furnace [BOF] for integrated mills is scrap metal also. The other portion being hot iron out of a blast furnace [BF]. So the BOF process, which is not scrap-intensive, is a significant scrap user, nonetheless.

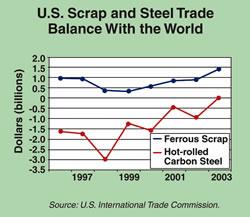

There are really only two and a half scrap depositories in the world today. One of them is in the U.S., the other in western Europe, and the half one is in Eastern Europe. The fact is, the scrap depository has been built up over 150 years.

What's happened to our integrated mills' input since the third quarter of '03? Coke's up 200 percent. Scrap's up at least 100 percent. Coal's up 50 percent ... the alloys—to the moon, Alice. This is what's driving the $30 surcharge that we've been carrying on integrated steel.

Robert Johns, director of marketing, sheet mill group, Nucor Corp.: The stories about raw material increases are well-documented relative to scrap, coke, and iron ore. Somewhat less well-documented have been increases in energy, transportation, alloys, and any mill component made from metal or energy-intensive products.

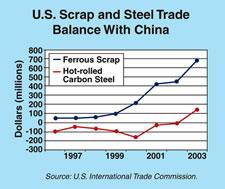

We urge readers to give some serious thought as to why reinvestment in raw materials assets resulted in dependence on, of all places, China for coke and South America for iron ore. This dependence has limited production. In turn, there has been increased pressure on scrap. When traditional exporters like Russia, Ukraine, Korea, and others cease scrap exports, the pressure for global supply shifts here.

Dependence has another byproduct. Until recently U.S. prices were in the lower quartile of global prices. We were less attractive. However, with certain foreign economies booming, the former exporters (and often dumpers) now refuse to ship here in deference to home markets. Welcome to the byproducts of dependence, and to globalization that didn't happen to go by the rules people agreed to play to.

Robert Stevens, CEO, Impact Forge Inc., and president, Emergency Steel Scrap Coalition:The first issue is demand, and the second issue is supply. First, Asia, and in particular China, is soaking up a tremendous amount of metal to meet their demands. Second, our trading partners in Russia, Ukraine, Venezuela, and South Korea are feeling such a shortage of steel scrap that they're restricting their supply of steel scrap exports. This has a ripple effect, in having people come after North American steel scrap.

|

Emanuel Bodner, president, Bodner Metal & Iron Corp. (representing the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries Inc. (ISRI): There are some who would ask you to believe that scrap is the primary cause of the current situation. But the high prices we currently see are coming from many sources. The current, and we believe, temporary, price pressures are being caused by global demand for steel rather than an assumed lack of domestic supply of scrap. Demand is high, prices are high, but there is no physical shortage of obsolete scrap. ISRI members are reporting that they are able to fulfill the needs of domestic steelmakers.

2. Where and when do you predict steel pricing will peak? How quickly will prices come down, and where will they stabilize?

Belanger, Ispat Inland:This bubble created by that boom will collapse, it has to collapse, bubbles always collapse. Our best bet is by midyear. My forecast is that band will probably peak in May or June around $550, $570 a ton, with corresponding spreads of $60 and $80 for cold roll above that, and if history is to be believed, $10 or $15 above that for generic, G90 hot-dipped galvanized. I think the deflation with regard to carbon steel is going to be only 10 to 15 percent off the high.

Atwell, Morgan Stanley:: We believe scrap prices will peak in one to two months [April to May] and drive steel prices down beginning in mid-2004. We believe steel prices will be meaningfully lower in six to 12 months.

Plummer, Metal Strategies:Prices will peak about midyear. We're already starting to see some price declines around the world with respect to scrap, and scrap will be the leading indicator. Once scrap prices start to decline, steel prices will fall.

China started to cut back its imports of both steel and raw materials in January and February, and that will ease pressure quite a bit. Prices in both other markets have already peaked, or are even starting to fall, in Europe, in parts of Asia, certainly in China. So while it is getting worse for buyers in the U.S.—May, possibly June will be very bad months for steel buyers, and much worse than anytime thus far—our view is that that should represent the peak, and then we should start to see steel prices peak and moderately decline.

|

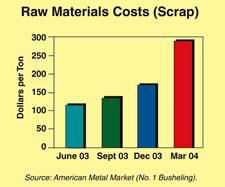

For No. 1 busheling, the type of scrap that's generated on factory floors of auto manufacturers and appliancemakers—American Metal Market is the source that's used for that, and they typically use the Chicago market—by June it won't get much higher than $300.

Hot-rolled sheet, the spot commodity, looks to be peaking at between $500 and $600 per ton. Some people think we're in for a real severe price collapse, temporarily, maybe for three to six months. Others say it could be a moderate drop, but will still remain at high levels but not as high as today, somewhere in the $350- to $400-per-ton range by the end of the year, perhaps.

With virtually all of the metals, the worst of these surges tend to be short-lived. If you look back to the other two [previous] periods, the worst lasted only six to nine months, and that's about what we think will happen here.

Joe Innace, managing director, World Steel Dynamics:Prices may have peaked already. The bellwether we track is the world spot export price for hot-rolled band (FOB the mill). The peak may be $525 to $550 per metric ton. It may decline to $325 per ton in September 2004 or continue declining through December 2004 to perhaps $270 per ton and may stabilize thereafter at about $300 per ton in 2005.

Here are reasons why we think this may happen: A surge in the recovery of obsolete steel scrap because of the elevated price may add 10 percent, or 120 million tons annualized, to the global supply of steelmakers' metallics in the second quarter of 2004. The incentive to collect steel scrap is at least two and a half times higher than last year. The U.S. scrap collector can now [late March] obtain at least $180 per metric ton for industrial scrap; the figure for much of 2003 was about $75 per metric ton.

Spot hot-rolled band prices in China have declined—a strong negative indicator. The recent decline in the hot-rolled band price raises a number of possibilities about future conditions in the Chinese steel industry: Steel buyers and users may have excess inventories; supply additions in the Chinese steel industry remain prodigious; and gains in domestic steel demand may be starting to slow as the government seeks to retard fixed asset investment in order to combat rising inflation.

Once steel prices rise to ultrahigh levels, a buyers' strike is a possibility.

Price volatility on the world export market is so great that an unexpected decline in 2004 should be expected. A pause in the price gains, and even a brief reversal, would fit the historical pattern. Steel demand outside of China, as of early 2004, was still fairly depressed.

Global steel production in the next few months could spurt more than expected. The current conventional wisdom is that steel mills the world over are constrained by raw material shortages However, [our data] does not indicate that there is a physical steel scrap shortage in China due primarily to the fact that about 86 percent of the gains in Chinese steel production in recent years have occurred via the BF/BOF route. In fact, the obsolete steel scrap recovery ratio from the Chinese reservoir was about only 39 percent versus 94 percent for the remainder of the world.

Bodner, Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries:Scrap markets are historically cyclical. In fact, they have likely reached, and perhaps passed, their peak.

3. Is this a short-term or long-term condition?

Belanger, Ispat Inland:It's not a temporary phenomenon; that's the underpinning as to why it won't go away. Integrated steel's been disinvesting in itself since about 1978. Integrated steel companies have not made their cost in capital since 1979 except for two years.

This is not a market swing. China's not going to back off. They've got those Olympics in '08, and they need to show the world that they're no longer a developing country. By God, if you don't think they're going to move heaven and earth to do it, go look at the Three Gorges Dam. The infrastructure requirements over and above the Olympics won't stop. They can't stop. I've read that between now and 2010, China is planning to build 10 cities the size of Columbus, Ohio.

Stevens, Emergency Steel Scrap Coalition:This is not a short-term situation, it's not "Well, it'll all be over in three months." This is a decades-long issue. China is looking to double their steel capacity beyond what they already have, so as they continue to look for raw materials around the world, it's going to exacerbate the situation even more.

Johns, Nucor:It is a short-term situation. We hope prices will never come down to pretariff levels. Pretariff price levels were physically killing this industry. How many more bankruptcies does the industry need to endure?

4. Are some geographic regions affected more than others? Are Asian, Canadian, Mexican, and European steel consumers experiencing the same shortages and price increases?

|

Belanger, Ispat Inland:Is the runup in prices on scrap and finished metals going on in China as well as the U.S.? The answer is a resounding yes. It hit there first. That's really what's driving up the price of scrap. This is global.

D. John Armstrong, manager, public affairs-operations, United States Steel Corp.:It's a global issue. It's in Asia; it's in the U.S.; it's in Europe. They're all being affected by the supply and demand issue on raw materials.

Tom Danjczek, president, Steel Manufacturers Association (SMA):Scrap tends to travel more from the coast than it does inland, because of freight costs, so those along the coast potentially are more affected than some of the inland companies due to freight costs. The Canadians and Europeans are experiencing similar problems with the amount of steel going to China.

Atwell, Morgan Stanley:Steel consumers overseas are facing similar cost problems, but steel prices are among the highest in the U.S.

5. The price increases and shortages appeared to start about the same time the Section 201 tariffs were lifted. Some fabricators see the price hikes as an attempt by the steel-producing industry to maximize profits when the tariffs ended prematurely. Is there any connection between the two?

Danjczek, Steel Manufacturers Association:This is not just a steel problem, it's occurring in other raw materials too. The lead, copper, brass people have the same problem, from a fabricator point of view. And they weren't involved in the 201.

Also, the integrated producers have seen significant increases in new raw material costs in coal, coke, and two significant prices in iron ore, so it's a raw material-driven problem, and not just steel. It's not related to the tariffs; it's primarily related to the raw materials increases. I think that's documentable.

Belanger, Ispat Inland:If Big Steel were capable of doing this, of orchestrating this kind of exercise, don't you think it would have been done 10 or 15 years ago? Integrated mills have been going bankrupt for the last 20 years. We thought hot-rolled sheet might get up to $330 this year. It sure wasn't on the business plan for $570.

Johns, Nucor:Absolutely none. The steel industry dodged a major bullet that could have been fatal to even more companies. The growth of demand elsewhere prevented a very nasty outcome from the termination of the 201. It is absurd to think that prices would have stayed at bankruptcy levels globally or here.

Stevens, Emergency Steel Scrap Coalition:I think the two—201 tariffs and steel surcharges—are totally unrelated. The 201 affected the amount of finished steel that was able to come in, but scrap and raw materials are the killer now, which is the other end of the animal.

6. What is the real definition of a surcharge? Why are surcharges imposed on materials that are contracted, even though, historically, contract prices have not been reduced when suppliers' material prices have been lowered?

Pat Furey, commodity manager, FreeMarkets® Inc.:A surcharge is a charge levied in addition to the established contract price to account for fluctuations in the cost of a metal alloy or raw metal. Surcharges are commonly used to pass on price increases to customers in volatile markets.

Johns, Nucor:Does anyone really expect a mill to absorb a $150-per- ton increase in raw materials costs on a product that sells for $300 per ton? Base price agreements have generally been honored with customers who did not break their agreements in price declines. Gets to the definition of agreements. They work both ways.

Keith Busse, president and CEO, Steel Dynamics Inc.:What's different this time is the range of volatility. I've never before in my 40-year career seen anything like this, where in four short months the price of scrap more than doubled. There's no way that you could absorb that.

7. Who is profiting?

Stevens, Emergency Steel Scrap Coalition:The No. 1 people making money on this are the U.S. scrap dealers. They are having a heyday at the expense of the steel consumers and the steel mills.

Busse, Steel Dynamics:The scrap people will say, "It's not all me," and the steel people will say, "It's not all me." Clearly, the scrap community has seen the best margins they've enjoyed in 40 or 50 years, or forever. Most of them would tell you that their profits were very strong. But to say that they're the only ones who profited would be absolutely incorrect. The steel industry's margins have moved up; some, for the first time in a long time, have earned a decent return on capital.

Plummer, Metal Strategies:It depends. This is a bit of a touchy subject. Is anybody gouging? It's tough to say. It's energy prices, it's scrap prices, increases that are part of making steel, and they're essentially being passed on. Most of the steel mills are doing better financially, certainly. I don't think anyone is making huge amounts of money. Most are coming through a four- or five-year period of very severe conditions. The scrap recycling industry is doing better, but they need to pay more to the collection system generating and bringing in the scrap.

Belanger, Ispat Inland:The conspiracy theory—is somebody sitting on 40 million tons of scrap? I don't think so. As the Kiplinger Letter points out, this isn't exactly a bonanza for the steel companies because of the cost increase. We're not making the money because it's going out of our pockets. U.S. Steel and Ispat are at $30 [surcharges].

8. What are steel producers doing to prepare for the future to take some of the volatility out of their pricing structure? Are they ramping up to meet current demands, updating processes and mill equipment? Is the creation of new U.S. mills in sight?

Busse, Steel Dynamics:We're no longer working through exclusive agents to buy our scrap. We're finding a way to work with large scrap generators that are also customers to bring the scrap back home. The biggest thing we're doing is focusing on scrap substitutes. Iron dynamics is a process that takes iron ore fines and conglomerates it with a recipe of ground coal, lime, and binding agents and produces a briquette. That briquette is placed on a hearth, a rotary hearth furnace, and we fire those briquettes with gas. The gas ignites the coal that's in the briquette, and the coal serves as an energy source to reduce the oxide to iron. Then it exits the rotary hearth furnace and [goes] into a submerged arc furnace, where it's reduced to liquid pig iron.

We have participated in a pilot project with [other companies] we call "Mosabe nuggets." It's somewhat similar to iron dynamics, only in the reduction process, we take it straight to a liquid state on the rotary hearth without a submerged arc furnace, using a whole different refractory base for the technology. It's a very effective technology and lower-cost than iron dynamics.

Johns, Nucor:We are developing scrap substitute resources. Raw materials are driving volatility. Our operating rates are strong across most facilities.

There is likely more [mill] consolidation in the future. Remember, this is a highly cyclical business. More importantly, the current situation is not an issue of melting and rolling capacity. The issue is getting raw materials to those facilities. There still is a global excess of subsidized and inefficient melting/rolling capacity. If there were an environment wherein bankruptcy is prevalent, no one in their right mind would build new facilities here.

Belanger, Ispat Inland:People will start building blast furnaces. Given the supply, do I see any shutter capacity coming back? Probably not. The issue is the raw material, not the rolling mills. You can't start mines up fast, the ones that are there are in such disrepair. Remember, the coking capacity is not in this country.

In 1976 we had 16,000 workers producing 6 million tons. Last year we produced about 6 million tons of steel with 7,000 workers and we're not done yet. So it's not like the steel industry is sitting on its you-know-what.

William Brake, vice president and general manager, International Steel Group Inc.:[About the March 11 announcement that ISG will restart a continuous caster and a BOF shop on the west side of its Cleveland Works, which has been shuttered since June 2001 by the former owner, LTV Corp., and will rehire 140 laid-off steelworkers.] Market conditions now warrant this investment. The cooperation we have received from the steelworkers makes this day possible. Domestic demand is strong, and we expect it to continue to be strong. [AISI Steel News]

Armstrong, U.S. Steel:The North American steel market manufacturing capacity is probably 10 percent of the global steel capacity. It would be very difficult for an area that only contributes 10 percent to overall steelmaking to really have much effect on the volatility of prices.

We are running at capacity. We're not going to be adding any capacity. But we're doing things to become more productive, and to reduce our cost of steelmaking. When we purchased National Steel, for example, we did that with an agreement with the United Steel Workers of America that allowed us to offer incentives to retirement-eligible steelworkers that would help us bring our productivity up by about 20 percent.

9. Will U.S. government regulation be warranted?

Stevens, Emergency Steel Scrap Coalition:What we would like to have happen is for the U.S. Department of Commerce to recognize the causes of the problem and to restrict the export of American steel scrap until the situation gets back to normal to set tonnage limits. If that 12 million tons [of exported scrap] drops back down to 6 million tons as it was in 2000, that additional scrap would dramatically reduce the cost of steel scrap. I like the idea of quantity restrictions. Then we're not trying to get involved in pricing; it's supply and demand.

The scrap dealers and to a lesser degree the integrated mills are saying, "Gee, we're happy with the market the way it is, we believe in a free market." But the reason we've got this situation is because of governments that are restricting export of their steel scrap, including South Korea, which is the second-largest purchaser of U.S. steel scrap. Free market, my foot.Danjczek, Steel Manufacturers Association: We belong to the Emergency Steel Scrap Coalition because it [increased prices] doesn't do us any good if our customers don't stay viable and competitive. The Chinese have had a huge subsidy by their currency manipulation. This government and this Congress have to decide whether we want to give the ranch away or not.

Belanger, Ispat Inland:I can't see it happening, but these are the free trade guys who brought you 201. You'd have to look into the mind of Karl Rove for that.

Bodner, Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries:Unfortunately and somewhat disconcertingly, the regulatory relief we most often hear mentioned comes in the form of scrap export controls. Clearly, this does not give due consideration to the entire problem. Suggesting that export controls would resolve the problem for steelmakers and steel users is not only incorrect, history shows that it could exacerbate the problem.

Jerry Jasinowski, president, National Association of Manufacturers:The U.S. is the biggest exporter in the world and has more to lose from an interruption of world commerce than anyone. Protectionism isn't a cure—it's a disease that will turn a bad economic cold into pneumonia. [The NAM board approved a resolution] opposing WTO illegal foreign controls on the export of industrial raw materials.

William Hickey Jr., president, Lapham-Hickey Steel Corp.:I keep wondering when someone in Washington, D.C., will connect the dots on our current economic problem in manufacturing.

10. Will the U.S. government intervene? If so, in what form? What is being done to force WTO-noncompliant countries to comply? What is being done in the absence of their compliance and "fair trade"?

Don Manzullo, R-Ill. (House Small Business Committee Chairman Manzullo held Small Business Committee hearings on the issue): The administration should immediately begin a study to consider the validity of imposing export controls on U.S. scrap steel. If the administration does not support export controls, it should draft a plan to negotiate the removal of current export restrictions on scrap steel and coking coal products imposed by Russia, the Ukraine, Venezuela, and China. Failure to remove the foreign export restrictions should result in a "hiatus" in the WTO accession process for Russia and the Ukraine.

The administration must continue to crack down on foreign currency manipulation and should support the U.S. manufacturing sector's effort to proceed with a Section 301 trade case against China for pegging its currency to the U.S. dollar.

In addition, Congress should pass H.R. 3716 to allow U.S. petitioners to file countervailing duty trade cases against nonmarket economies, which would allow us to get tougher on China's trade abuses.

The administration should also review all existing antidumping and countervailing duty orders placed on foreign imports of steel into the United States to see if they are warranted considering the tightened markets in America.

The Senate must pass the Energy Bill (H.R. 6) and let the president sign it into law so that we can increase energy production in this country and lower the production costs for steel producers.

[The administration also should] assess threat to national security and investigate reported shortages of scrap steel and coking coal via a Section 332 investigation.

Sen. Richard Durbin, D-Ill.:I have long been concerned about the price and supply of steel, especially for small manufacturers. We need to study the possibility of imposing export controls on U.S. scrap steel.

The Chinese government's decision to undervalue its currency violates the spirit and letter of the world trading system, of which China is a partner. It is killing manufacturing jobs in the U.S. We need to send an unmistakable signal to the Chinese—stop the market manipulation or pay the price with your trading partners. I support legislation, which has broad bipartisan support, to penalize the Chinese government for its undervaluation of the yuan by instituting a 27.5 percent tariff on Chinese exports.

There is much the U.S. can do to create the circumstances for and to enforce fair trade. Antidumping and countervailing duty laws can provide relief for domestic industries injured by dumped or subsidized imports by authorizing additional duties to offset these unfair trade practices.

American Metal Market, 1250 Broadway, 26th floor, New York, NY 10001, www.amm.com

Bodner Metal & Iron Corp., 3660 Schalker Drive, Houston, TX 77026, www.bmicorp.com

Emergency Steel Scrap Coalition, www.scrapemergency.com

FreeMarkets Inc., 210 Sixth Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15222, www.freemarkets.com

House Small Business Committee, House Office Building, 2361 Rayburn, Washington, DC 20515, www.house.gov/smbiz

Impact Forge Inc., P.O. Box 1847, 2805 Norcross Drive, Columbus, IN 47201, www.impactforge.com

Ispat Inland Inc., 30 W. Monroe St., Chicago, IL 60603, www.ispat.com

Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries Inc. (ISRI), 1325 G St. N.W., Suite 1000, Washington, DC 20005, www.isri.org

International Steel Group Inc., 3250 Interstate Drive, Richfield, OH 44286, www.intlsteel.com

Lapham-Hickey Steel Corp., 5500 W. 73rd St., Chicago, IL 60638, www.lapham-hickey.com

Metal Strategies, Brandywine Business Park, 1205 Ward Ave., Suite 1, West Chester, PA 19380, www.metstrat.com

Morgan Stanley, 1585 Broadway, New York, NY 10036, www.morganstanley.com

National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), 1331 Pennsylvania Ave. N.W., Washington, DC 20004, www.nam.org

Nucor Corp., 2100 Rexford Road, Charlotte, NC 28211, www.nucor.com

Senate Office Bldg., 332 Dirksen, Washington, DC 20510, www.durbin.senate.gov

Steel Dynamics Inc., 6714 Pointe Inverness Way, Suite 200, Fort Wayne, IN 46804, www.steeldynamics.com

Steel Manufacturers Association (SMA), 1150 Connecticut Ave. N.W., Suite 715, Washington, DC 20036, www.steelnet.org

United States Steel Corp., 600 Grant St., Pittsburgh, PA 15219, www.uss.com

World Steel Dynamics Inc., 456 Sylvan Ave., Englewood Cliffs, NJ 07632, www.worldsteeldynamics.com

About the Author

Kate Bachman

815-381-1302

Kate Bachman is a contributing editor for The FABRICATOR editor. Bachman has more than 20 years of experience as a writer and editor in the manufacturing and other industries.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI