Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Coil-fed fabricating

A northern Italy fabricator hopes to boost productivity and materials savings with a new coil-fed punching and laser cutting line

- By Dan Davis

- July 11, 2016

- Article

- Laser Cutting

Figure 1

Fiorello Trevisan, production manager (left), and Giorgio Tomasella, general manager, stand in front of Elleci’s new coil-fed punching and laser cutting line.

When most people think of Italy, they think of historic structures and memorable food. Some fabricators might have a slightly different perspective, however.

These manufacturers likely know Italy, particularly the country’s northern region, as the home to some of the leading machine tool builders in the world. UCIMU, a trade group representing Italian machine tool builders and automation equipment integrators, reported that machine technology exports to the U.S. reached a value of $271 million in 2015, which made the country the No. 1 export destination for Italian-made machine tools. That total dollar value represented a 10 percent increase over 2014 exports.

Armando Varricchio, the Italian ambassador to the U.S., summed up the Italy-U.S. manufacturing technology relationship succinctly at an Italian Trade Agency event in Chicago at the end of March: “We have only one way to go—and that’s forward.” He added that while manufacturing technology represents only a portion of overall trade between the two countries, it is a valuable segment. If Italy is to be viewed as a world leader in advanced manufacturing technology, it needs to be represented on U.S. manufacturers’ shop floors.

On a recent trip to Italy, sponsored by Dallan S.p.a., an Italian manufacturer of roll forming lines and tools (see Expanding on roll forming success sidebar), and Dalcos, its cutting equipment division, The FABRICATOR got to witness a new take on punching and laser cutting on the fabricating shop floor. It’s a coil-fed fabricating line, and this Italian-made metal processing line will soon have a home in the U.S.

The Universal Need: Diversification

Elleci S.p.a. is not too different from other manufacturers of metal components and assemblies found in other parts of the world. It has found that doing business as it did 20 years ago simply doesn’t work in today’s more competitive market.

Elleci was founded almost 50 years ago as a maker of electrical cable channels and cabinets. It developed a reputation as a dependable metal fabricator, which enabled it to build a new facility in 1994 and expand it in 1998. Today the company has 150 employees and 200,000 square feet of manufacturing space, from which it delivers its metal products to customers in northern and central Italy for the most part.

In the early part of the 21st century, however, the fabricator found itself in an unfavorable position. One large customer dominated its sales, and this multinational manufacturer of electrical products, a very good customer for a long time, was feeling the pressure from competitors in developing parts of the world, where labor costs were cheaper than those in western Europe. As a result, the OEM decided to shift some of its own production to emerging regions. That move left Elleci with a need to attract business to replace the work it had lost.

In the ensuing years, the fabricator repositioned itself from being “production-oriented to customer-oriented,” according to Giorgio Tomasella, Elleci’s general manager. The fabricator invested in new fabricating equipment, engineering talent, and design tools.

“We provide products but also services,” Tomasella said. “If our customers want to give us 3-D drawings, for example, it’s OK. We have people working with 3-D design. We can now offer special features on designs and provide advice. We can help them.”

Elleci, which typically works with mild steel in thicknesses of 0.125 in. (3 mm) and thinner, today has a broader customer base. Its onetime largest customer now represents only 30 percent of its annual sales, whereas it was as high as 80 percent at one time. Tomasella said the company’s annual revenues are $20 million.

Figure 2

Coils of different sizes are kept beside the coil-fed punching and laser cutting line and an older coil-fed punching line. Because the coils are sized to the width of the part to be produced from them, the coil-fed fabricating process results in a limited amount of scrap when compared to typically sheet-fed processes.

The shop floor has changed dramatically as well over the past 15 years. Laser cutting machines and panel bending equipment with automated load/unload capabilities are able to run unattended during the night shift. Jobs don’t entail thousands of pieces anymore; the average job size is 400 pieces. Elleci is holding more inventory for customers looking for just-in-time delivery of key metal components. The fabricator also has boosted its finishing capabilities with a new powder coating line with three booths that can accommodate quick color changes; the company is now changing powder color as many as 20 times in just one shift.

Of course, Elleci is still interested in further diversifying its customer ranks. One new tool that will prove useful in achieving this goal is its new ELXN coil-fed punching/laser cutting line from Dalcos (see Figure 1).

Fabricating From Coil

Elleci was no stranger to working with coil. It has 10 stamping presses, with the largest having a 200-ton capacity. It also was familiar with roll forming technology and has a Dalcos coil-fed punching line that was installed in 2003.

The new ELXN line, which was installed in early 2016, will allow Elleci to pursue customers with similar metal products but of different lengths, up to 13.1 ft. (4 m).

“We needed this kind of machine,” Tomasella said. “With our older machines, you had to load the part, and it takes time to cut the parts to the correct width.”

That’s the most noticeable advantage gained from the Dalcos coil-fed fabricating line (see Figure 2). The line can adjust to the width of the coil. Elleci’s line can accommodate widths as small as 2.6 in. (68 mm) or as large as 3.3 ft. (1 m). If the part width corresponds to the width of the coil, the fabricator can reduce scrap, especially compared to a similar part cut from a standard-size piece of sheet metal.

The line begins with the uncoiler that feeds the metal to a CNC precision feeder (see Figure 3). The Elleci uncoiler has an 8-ton capacity. The uncoiler speed can be optimized so that it is continuously providing sheet metal to the punching station.

The feeder, which has a built-in straightener that helps to remove curvature and coil set in the metal because it was wound on a reel, guides the material into the servo-electric punching machine (see Figure 4). The punching tools, attached to two “tool arches,” as described by company literature, move along the Y axis to punch, form (such as embossing), and perforate the metal as it proceeds through the station.

The tool arches can accommodate standard turret tools from a variety of tooling manufacturers. The station on the Elleci line has a 20-ton punch capacity and a tapping unit.

If Elleci engineers decide at a later date that they want to set up tools in a different configuration than the tool arches currently allow, they can commission Dalcos to create new ones. Elleci can then slip the arches out and replace them with new ones. Up to 48 standard turret tools can be accommodated in a punching station for one of these coil-fed lines.

(Fabricators looking for more productivity also can request a servo-electric stamping press to be added to a line. This type of press can deliver a ram force of 60 tons and a processing speed of up to 150 strokes per minute, according to Dalcos officials.)

If the part being fabricated at the punching station is shorter than 13.1 ft. (4 m), a shear cuts the product from the coil and sends it to the laser cutting station (see Figure 5). If the product is longer, the prepunched material enters a loop control unit and is later cut off by the laser.

The part enters the self-contained laser cutting machine where a 2-kW laser, generated by an IPG fiber laser power source, handles the cutting of notches and special shapes (see Figure 6). Before cutting begins, however, a camera detects the position of the holes or forms to ascertain exactly where the cutting should take place on the part.

The punching and laser cutting stations are designed so that they can be operated simultaneously. In fact, the laser cutting machine can be sheet-fed if Elleci personnel choose to tackle a fabricating project in this manner.

When laser cutting is complete, the part is delivered to an unloading table, where it awaits delivery to a downstream process such as welding or painting.

Tomasella admitted that the company’s engineers are still getting used to the new equipment. The goal is to move more parts from the turret punches to the line, but first they must figure out which parts make the most sense for migration to the new line.

“You observe what you are doing on other punching machines, and then you start seeing the parts that you can do on this machine,” said Andrea Dallan, CEO of Dallan.

While Elleci is still learning about the potential of its new coil-fed fabricating line, it has worked with it enough to know that it is making a big impact on production. For example, for one family of seven laser-cut parts, production time averaged 1.5 minutes per part. On the coil-fed line, the production rate for the same family of parts dropped to 0.95 minute per part, according to Tomasella. Similar savings have been found elsewhere, he added.

Elleci also has seen better material utilization. Parts that once were nested on sheets and processed on punching or laser cutting machines typically resulted in about 15 to 20 percent of the sheet headed for the scrap pile. That was usually in a skeleton form. On the Dalcos line, only 2 to 3 percent of the material is ending up as waste.

The success that Elleci has found with the line will not be limited to northern Italy. Soon this technology will find a home at a U.S. manufacturer of metal residential products.

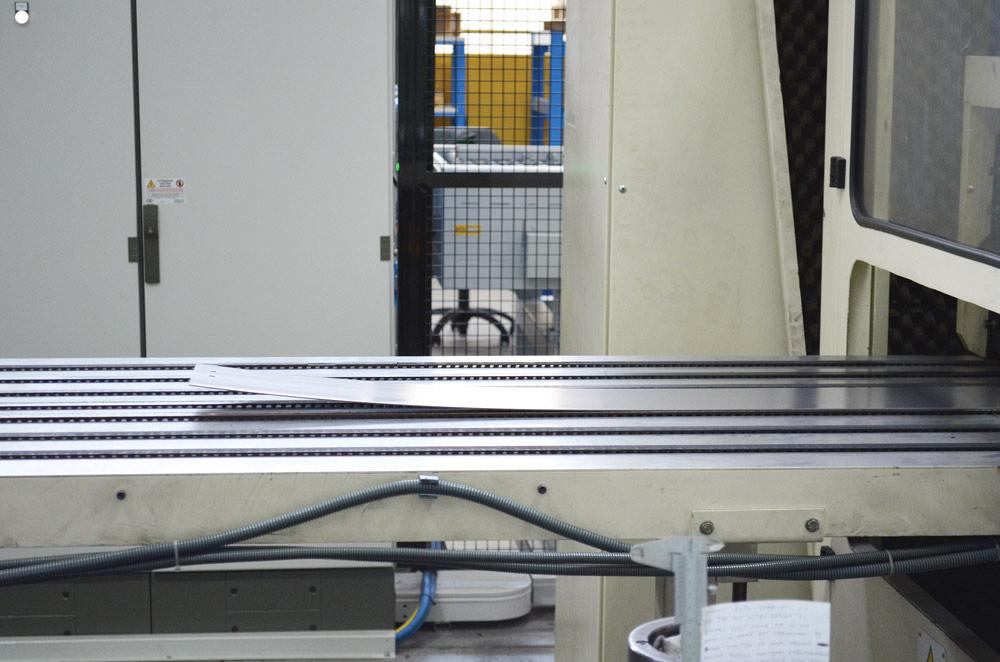

Figure 4

The punching station uses standard turret punch tooling available from several different manufacturers.

Elleci S.p.a., www.ellecispa.net

Dalcos, www.dalcos.com, Dallan S.p.a., www.dallan.com, c/o MMT International, 972-241-0790, www.mmtinternational.net

Expanding on roll forming success

Upon completion of his university studies, Sergio Dallan founded his company in northern Italy in 1978. At first it was dedicated to the development of tooling for cold roll forming, but soon afterward it started to build roll forming machines.

Today the company has 150 employees and annual sales of approximately $30 million a year. It produces about 100 roll forming lines and coil-fed punching lines per year. The company holds close to 100 international patents.

Dallan’s early reputation was built on its success in developing roll forming equipment for thin materials. Eventually this led to the successful development of lines that handle prepainted material, such as blinds for windows. Today Dallan manufactures lines that can cut the blinds to size, form them, place plastic end caps on them, collect them, and thread them so that one blind package is completely put together.

Dallan also has achieved attention for its roll forming lines dedicated to the production of T-bars for ceiling grid systems and for metal frames used to hold drywall in residential construction.

Dalcos, the company’s cutting division, launched its coil-fed laser cutting systems and combination systems in 2014 after a three-year research and development process.

About the Author

Dan Davis

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8281

Dan Davis is editor-in-chief of The Fabricator, the industry's most widely circulated metal fabricating magazine, and its sister publications, The Tube & Pipe Journal and The Welder. He has been with the publications since April 2002.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/09/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:55

In this podcast episode, Brian Steel, CEO of Cadrex Manufacturing, discusses the challenges of acquiring, merging, and integrating...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI