Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

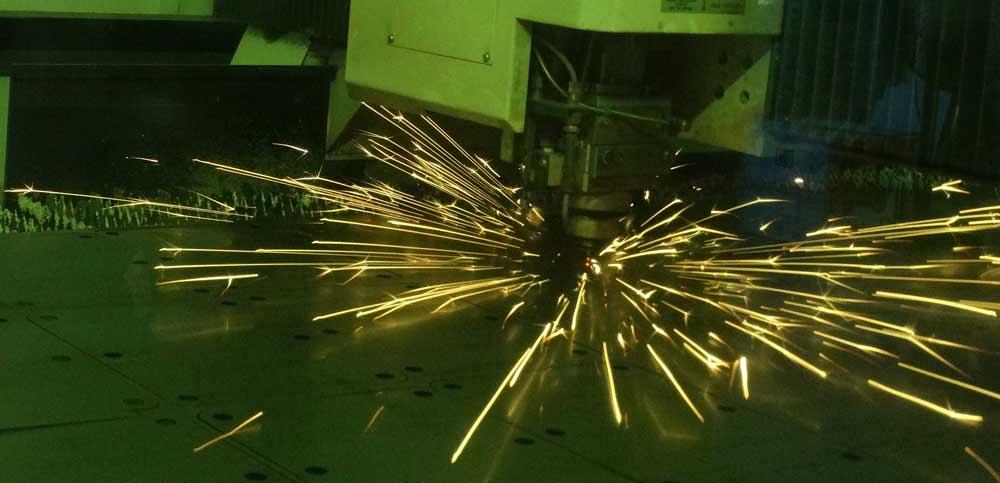

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Laser cutting leads to business diversification

Drive-thru order-point fabricator diversifies with a fiber laser

- By Tim Heston

- January 8, 2018

- Article

- Laser Cutting

This shows the edge of Uni-Structures’ signature pivoting order-point canopy. Photo courtesy of Uni-Structures Inc.

If you’ve ever pulled up in the rain to the drive-thru for a burger or chicken sandwich, you may have benefited from an innovation made popular by a 60-person fabrication shop northwest of Atlanta. A canopy keeps everything dry—no more cracking the window and having the order-taker straining to hear you. So why is this significant?

“About 70 to 80 percent of the store’s annual revenue passes through the drive-thru. And you can lose between 50 and 60 percent of your drive-thru business during inclement weather.”

So said C.J. Mays, design manager for Kennesaw, Ga.-based Uni-Structures Inc., the fabricator that makes those canopies, menu boards, and other drive-thru components. Uni-Structures has grown to about 60 employees by focusing on drive-thrus, including those at banks and car washes, but mostly in the industry that has made the drive-thru ubiquitous: the quick-service restaurant, or QSR.

At first glance, a drive-thru looks to be an architectural element that could benefit from the flexible tooling that’s at the heart of custom fabrication. After all, drive-thru menu boards aren’t ordered in the thousands. How could a company possibly justify designing and ordering a tool dedicated to one product?

But look closely at a canopy drive-thru at many QSRs—especially one supplied by Uni-Structures—and you’ll see sections that look like narrow sheet metal panels. Look closer and you’ll find that they’re not sheet metal panels at all. They’re extrusions, components that greatly simplify fabrication, assembly, and on-site installation.

That strategy of using extrusions when and where possible is a significant element of Uni-Structures’ business model. Extrusions are the building blocks that have helped the business grow quickly.

But last year the company added another technical capability: A 4-kW fiber laser. Is this laser investment the first step toward an utter transformation, one of precision cutting, bending, welding, with no need to design tooling or rely on an extruded shape? According to Mays, not at all. Instead, the laser will help the company diversify and participate in special projects, ones that use visual elements from its core drive-thru business, and yet in most cases aren’t likely to be repeated anywhere else.

Signs of Change

Uni-Structures CEO Michael Barnes used to be in the sign business. “He owned a sign company, installing someone else’s product,” Mays said. “He got fed up with the quality of the product he was installing. He thought customers deserved something better.”

One afternoon, not long after launching his company, he noticed people lined up in drive-thrus in the rain, barely cracking their window and shouting into the speaker (the “order post,” in QSR jargon) to order their food. “He thought, ‘That’s silly. Why not put a canopy over the order-point structure?’” Mays said. “That’s when the lightbulb went off.”

Of course, there’s a reason that drive-thrus remained utterly simple for decades: revenue. What if someone driving a truck were to damage the canopy and shut down the drive-thru? There goes a restaurant’s principal sales source. For this reason, Uni-Structures patented a mechanical pivoting system that, when hit, used gravity to pivot back into place. This minimized damage to the vehicle hitting it and left the overall structure undamaged—and the drive-thru could remain open for business.

An on-site technician finishes installing an order-point canopy system for a customer. Photo courtesy of Uni-Structures Inc.

“We then integrated the speaker and microphone into the canopy,” Mays said. “We now call it our ‘order-point canopy.’ We installed our first in 1995, and we’ve installed tens of thousands of them ever since.”

Repeatability and Scalability

Installing so many order-point canopies probably never would have happened if the company hadn’t taken its unique approach to design. When Barnes worked in the sign business, he became all too familiar with a reality of the job shop. Every job is different, and with that comes all sorts of variability and business planning headaches.

So Barnes decided to focus on products for the QSR drive-thru. One industry headache, though, was installation time. “Installers in this business may be on-site for two or three weeks. We’re usually there just two or three days.”

Uni-Structures accomplishes this by getting its installers involved in product design on the front end. They point out any area of the design that could make it more complex to install, and this includes any part size variability and components not coming together as they should. Here is where extrusions play a critical role.

Mays conceded that the company’s extrusion strategy is counterintuitive, particularly considering the die development time involved. “We can spend thousands to have a die made, with a lead time of one to three months,” he said. “We evaluate the die and go back and forth with our extruder. We can spend a lot of time and money getting the shape we really want. There’s a big expense.”

But the expense is worth it, and a quick glance on the shop floor shows why. Over the years the company has designed several hundred unique extrusions that make up the framework (usually carbon steel) and external structure (usually aluminum) of drive-thru components.

The extrusions help make everything repeatable—no having to deal with sheet metal thickness variations, brake operators or welders “making things work.” The extrusions also helped Barnes’ strategy for scaling up his product lines.

“Once [the order-point canopy] took off, [Barnes] got out of the sign business,” Mays explained. “It was not scalable or predictable. He wanted to go with something predictable, something we really believe in.”

When cut and assembled in the right way, the extrusions eliminate all external welds on most products, which has in turn reduced the need for grinding. Extrusions also are fabricated to exact dimensions, which speeds and simplifies on-site installation. If you see a hand grinder in use on the floor, it’s probably being used to add specialized finishes.

Mays held up two extruded shapes that the company has been using for years. “If you have these miter-cut, these mate up cleanly, and you have what we call our ‘drip edge.’” It’s basically a small C-channel that serves as a tiny gutter for rainwater. It is difficult to form on a press brake quickly and consistently, but easy to extrude, assemble, and weld. And again, all the welding goes on the interior of the assembly; the shell has nothing but clean lines and perfectly mated surfaces.

Designers also ensure that the extruded part could be cut and used on a variety of different products. One extruded shape from one die could be used for dozens of different drive-thrus.

About Diversity

Although it did have a plasma system, the shop used to process much of its sheet and plate on a routing table, which required a team to work two shifts, cutting mostly aluminum sheet metal and plate. It replaced the router with an Optiplex Nexus 4-kW fiber laser from Mazak. What that team accomplished in two shifts on the router now can be cut within hours on the fiber laser.

“During the first shift of that laser being operational, we had no need for a second shift,” Mays said, “and we really couldn’t fill up an entire first shift.”

He added that now, if somebody in the shop needs an extra part to be cut, supplying it is no problem. “We used to have to work to fit an extra job on the router’s schedule,” Mays said. “But now, if we need an extra part cut, the guys say, ‘No problem. We’ll be back with the part in five minutes.’”

Of course, that routing table sufficed for years. How, exactly? It goes back to the company’s extrusion strategy. Its products are primarily made of extruded components; they just don’t have that many sheet metal parts. The majority of parts the laser does cut are those for which creating an extrusion die just wouldn’t make sense. All of the company’s products have a flat surface of some sort, and most of these are extruded shapes that the company has used hundreds of times over the years; hence, an extrusion for those flat surfaces makes sense.

This leaves few flat parts for the laser to cut, so most parts that come off the laser flow to the press brake for bending. On that brake is a sign showing allotted times for operators, which is a hint at how the shop had to alter its scheduling and part flow strategy shortly after buying the laser in early 2017. Because the laser cut so many parts so quickly, workers at first lined up at the brake to bend their parts. Today each worker has a designated time for press brake time during a shift. When workers need parts bent, they work on other jobs until their timeslot comes up.

This begs the question: If a router’s capacity sufficed before, why buy a laser now—and a high-powered fiber laser at that? It goes back to a strategy many custom fabricators are very familiar with: diversification.

The company is already filling up the laser on second shift with overflow contract work from other fabricators in the area, and with the growing local economy leading to capacity constraints at many local fab shops, there’s plenty of overflow work to go around.

Still, contract work wasn’t the main reason that the company bought a fiber laser. It made the investment to gain more special projects work. At least some of that work could evolve into new product lines and, ultimately, another consistent stream of revenue.

For instance, the company recently designed and installed a building exterior, along with some interior elements, for a manufacturer of large earth-moving equipment. The design incorporated extrusions, but it also involved several cosmetic elements.

The cosmetic elements are unique, and making them out of extrusions just wouldn’t make sense. So in this case, laser cutting, bending, and welding pieces in-house makes sense.

Growth Path

Uni-Structures didn’t purchase the new laser just to overcome capacity constraints (though to be sure, the router was a constraint process). The purchase was instead part of the company’s long-term strategy. “It was not about looking at what we’ll need over the next year,” Mays said. “It was about what we’ll need over the next 10 years.

“We’re gearing up to solicit new business for the first time in 20 years,” he added, explaining that the company has grown to what it is today without a formal sales effort. Owners and managers built relationships with builders, contractors, architects, franchise owners, and those at the corporate level of some of the nation’s largest QSRs. Uni-Structures is on the corporate-approved list of many chains; when the need arises for a drive-thru, Uni-Structures gets a call.

“But we can’t start to stagnate,” Mays said. “Many new QSR chains are out there, and we need to be in front of them.”

The fabricator can offer its pivoting order-point canopy and other patented and patent-pending innovations. But it also now can make special products, and its new laser is there, ready to serve the quick-service industry—quickly.

Uni-Structures Inc., www.unistructures.com

Mazak Optonics, www.mazakoptonics.com

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI