Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Quick response, Texas-style

When opportunity knocks, PI-CO Precision opens the door quickly

- By Tim Heston

- May 14, 2014

- Article

- Laser Cutting

During The FABRICATOR’s Leadership Summit, held in Austin, Texas, in early March, Glen Pierce and his brother-in-law Jerry Jorden opened the doors of PI-CO Precision Fabrication (see Figure 1) to attendees for a tour. As Pierce, PI-CO’s vice president, led his tour group to the welding area, he pointed to the roof rafters showing an addition made to the building several years ago.

It started with a phone call that ended with a $1 million purchase order—a massive job, both in volume and workpiece size, for a fabricator that brings in about $8 million annually—but the reality was that the company simply didn’t have space to do the job properly. The terms sounded good, the customer agreement looked solid, and PI-CO could use the extra space to take on more work. So with a massive PO on the line, the fabricator sprang into action and built an addition onto the plant within 60 days.

“At a big company, it would have taken 60 days of meetings to decide whether we were going to even take the job or not,” Pierce said, adding that of course not every job warrants adding more space to a building. Still, being a small organization, PI-CO doesn’t have much of a bureaucracy. It makes decisions quickly. “That’s one of the things we take pride in,” Pierce said. “If a customer calls in, we respond promptly to their needs.”

Bowling for Diversity

The Hutto, Texas-based business has 37 employees who work in 42,000 square feet of manufacturing space. That’s far more space than PI-CO’s owners thought they would ever need when they launched the business out of a bit of rented space in neighboring Round Rock, behind the local bowling center.

The Pierce family has some history in the bowling business. They’ve also dabbled in the construction business, RV storage business, and fiberglass bathtub manufacturing. Glen Pierce even has some experience in the most unpredictable business of all: politics. “I was mayor of Hutto for six years,” he said, “but I got out of that mess. I couldn’t get anyone to run against me, so I quit.”

Pierce’s father Sonny worked as a welder for years until the mid-1970s. At that point he was helping his brother who had recently launched a fiberglass bathtub manufacturing business. Before long Sonny was making more money selling fiberglass bathtubs than he made welding, so he went to work for his brother full-time.

Timing wasn’t on his side. This was the late 1970s. Texas itself was experiencing a relative boom time, thanks to rising oil prices, but the country overall, of course, wasn’t. Thanks to the oil embargo, gas shortages, and a generally struggling national economy, by 1978 the tub business had slowed dramatically. At that point the Pierce family regrouped. People weren’t about to upgrade their homes if their job was on the line, they thought, but they still would enjoy a relatively inexpensive night out.

At the time Round Rock didn’t have a bowling center. So the Pierces built one in front of the old bathtub manufacturing facility. And as the bathtub business started shutting down, the Pierces devoted more time to the bowling alley. “After two years, though, we figured there wasn’t a whole lot of money in the bowling business,” Pierce recalled. “So we thought about what else we could do, and Dad wanted to start a sheet metal company.”

His father bought several pieces of new and used equipment and rented out 2,000 sq. ft. of the bathtub manufacturing facility. PI-CO opened its doors in 1982, and a dozen years later the company moved to its current location in Hutto, which initially had 15,000 sq. ft. “We thought that was more than we were ever going to need,” Pierce said. “Well, now we’re up to 42,000.”

Many Hats

During the Leadership Summit tour (see Figure 2), one attendee asked, “So who does your sales?”

Figure 1

PI-CO Precision Fabrication opened its doors for a shop

tour during The FABRICATOR’s Leadership Summit, which

took place in Austin in March.

“Myself and the president of the company, Jerry Jordan,” Pierce said, adding that most of the work comes to the shop via word-of-mouth.

“Who handles your quality?”

“Everybody does,” he said, adding that the shop does employ one full-time person dedicated to QA.

“Where is your programming staff?”

Pierce shook his head and chuckled. “We’re pretty lean around here. We’ve got only six people in administration. We have myself and my brother-in-law. My sister does the books. We have one scheduler, we have one programmer, and we have one person running the warehouse. We have one quality assurance professional. I take care of all of our ISO and safety training, insurance, and financing, talking with the banks. Jerry does most of the quoting, deals with customers, and oversees the production of the shop. Everybody wears multiple hats.”

Besides those six, the remaining employees take ownership over a manufacturing process, be it laser cutting, punching, bending, or welding. The company doesn’t have dedicated setup personnel. Instead, each employee sets up his or her own machine, operates it, performs basic maintenance, and cleans his or her work area.

As Pierce put it, “We don’t have operators. These guys can set up a machine and run it from start to finish. Our average length of employment here is more than 15 years. We pay 100 percent of their health insurance. We have a 401(k). We have a bonus program.”

He followed up with a key comment that he said drives PI-CO’s approach to the fabrication business: “We don’t hire a lot of new people, and we work overtime if we have to. But we don’t like to hire them and just lay them off. We spend too much time training them.”

The fabricator taps into a broad customer mix, which helps smooth the peaks and valleys of the business cycle and provides a somewhat steady flow of work for its longtime employees. That’s a luxury bowling and bathtub-making just didn’t have.

Managing Manufacturing Capacity

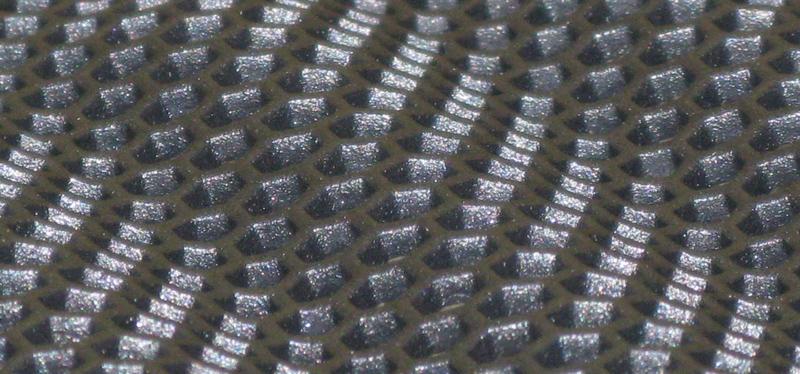

At this writing, PI-CO is installing a new solid-state disk laser system from TRUMPF that promises to provide additional cutting capacity. Specifically, the company hopes to move more parts off its LVD Strippit punch press to the new laser. This in turn will give the fabricator more capacity on the punch press, on which the fabricator uses a fair number of form tools that create complicated embossments, offset geometries, louvers, and flanges—common on most of the company’s electronics enclosure jobs (see Figure 3).

Figure 2

Glen Pierce, vice president at PI-CO Precision Fabrication,

shows some of the company’s handiwork, a sheet metal

chassis designed for a computer animation system.

Determining and communicating those customer requirements can be the most difficult part of a metal fabrication business, and to that end, the company has set up about a half dozen computer terminals on the floor, all running Global Shop Solutions enterprise resource planning software.

When a job traveler arrives at the workstation, the technician scans a bar code to view the models and prints for the finished product on a nearby screen (see Figure 4). If a technician has a question about, say, a certain hem, he can access the drawing and zoom in to see exactly what the customer is asking for. It also helps the company uncover any discrepancies between the model and the drawing in the paper traveler.

At some point, Pierce said, the company would like to replace paper travelers entirely with computer terminals. That way, when the job arrives, the technician knows he has the latest and greatest revision.

PI-CO’s programmer works with the customer-provided part file, be it a 2-D drawing or 3-D model, but the company refrains from conducting extensive design work. “PI-CO does not have an engineer on staff or a design group, but we will assist the customer with practical application information,” Pierce said. If, for instance, a customer could save money by loosening this tolerance or lengthening that flange width, PI-CO managers don’t hesitate to give advice.

Why Metal Fabrication Stands Apart

The family knows how quickly failure can follow success, and often that failure comes from forces outside of the business owner’s control. When interest rates skyrocket and construction suffers, you can’t force people to buy bathtubs. You can’t force them to spend money on entertainment, even bowling. Those businesses are beholden to consumer behavior in specific sectors.

But metal fabrication is a different animal. Shops need not depend on one customer or industry. They can streamline operations through better organization, information sharing, and manufacturing technology. Businesses can diversify their customer base to mitigate economic ups and downs. At PI-CO a computer chassis for computer animation may sit next to a subassembly destined for a customer in the defense business. Such diversity builds the foundation for a strong business model.

The company sells itself as a reliable source of manufacturing capacity. That requires having enough capacity on hand to handle the highly variable work flow of the job shop, hence the investment in the new disk laser. It also requires clear communication to ensure everyone is working with the right information, hence the investment in ERP software and those screens on the shop floor. And it takes the ability to move quickly, hence the lean atmosphere and lack of bureaucracy.

One metric on the wall in every room at PI-CO shows the mortar bonding the business model together: an on-time-delivery rate that hovers around 99 percent.

A Simple Approach to ISO

In 2004 PI-CO Precision Fabrication, Hutto, Texas, already had a quality manual, but more customers were asking about ISO certification, so PI-CO obtained one. But the company didn’t go about documenting every minute detail involved in the thousands of different products the firm fabricates. Instead, they worked with ISO consultants to develop a simple flow chart, or process map (see figure), which at an upper level documents PI-CO’s procedures.

Vice President Glen Pierce pointed to one flow chart on the wall of the assembly department. “That’s our entire ISO program,” he said, adding that every department has its own flow chart that describes what needs to take place to make a quality part.

“We try to keep it simple,” Pierce added. “If you go to our [ISO documents] online, you can click on our flow charts, and it will tell how everything is processed. It’s very straightforward.”

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI