Contributing Writer

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Washington women weld at the 'Y'

Students learn by doing in their community

- By Bob Hollingsworth

- August 28, 2003

- Article

- Arc Welding

|

It's a drizzly, blustery Pacific Northwest morning in November with the gray light of dawn coming up behind the Cascade Mountain Range.

Crew Leader Cheryl Boxx, clad in Carhartts®, squares her hard hat in place and begins checking scaffolds, rigging, welding equipment, and her teammates' assignments.

"Minnesota" Mary Kuebelbeck cranks up the rock 'n' roll, gets the chop saw and torch ready, and starts selecting channel and angle iron.

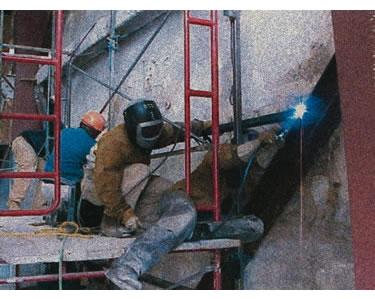

Meanwhile, Angel Adam pulls on her leathers and full-body harness, grabs a welding helmet, and begins the climb to the top of a 31-foot scaffold.

Out in front, Tiana Wicklund approaches "Big Bad Blue," a Miller Electric Blue Star 180K. She checks it over, including leads and engine oil, knowing that the machine will be online for a 10-hour day of serious welding, burning 7018 rod. She punches the Go button, the machine coughs once, catches hold, and soon steadies into a high-amperage-producing cadence.

At the other end of the show, Samantha "Sam" Sylvester is dialing in "Honest Abe," a Lincoln Electric SP-135T gas metal arc welding (GMAW) machine, running 0.035-inch solid wire and cooking with Airgas' Gold Gas. She has this unit tied into the facility's main electric panel.

At this point, this may sound like an Army ranger unit preparing for battle—but these are the so-called "Welding Chicks," student welders who are, some say, as famous as rock stars in the greater Whatcom County area in Washington.

They came forward as volunteers to complete one mission: erect the steel superstructure for a 24-ft.-wide by 31-ft.-tall indoor rock climbing wall at the Whatcom Family YMCA in Bellingham.

How the Project Started

YMCA Director Dave Harding and his management team noted the popularity of rock climbing walls and the success of their initial 31-ft.-tall wall. This led to plans for a 65-ft.-tall rock wall housed in a glassed-in atrium.

Before long Harding and his team had a design off the boards, bids in hand, and a signed contract. Dawson Construction Inc., Bellingham, Wash., installed the steel superstructure, and Entre Prises Climbing Walls, Bend, Ore., designed and fabricated the 42- by 42-in. panels that constitute the rock face. Entre Prises' field personnel, with Harding's in-house personnel, known as his "rock jocks," installed the bolt-up rock face.

And then the honeymoon ended.

Although the concept included installing the old wall across from the new one, no money was left for it in the budget.

In 2001 my welding students from Western Washington University previously welded up the ornamental ironwork that graces 72 frontal ft. of the YMCA building's exterior. However, this time no Western Washington University welders were available. To help resolve this problem, Bellingham Technical College instructor Jer Mondau and I formed a joint venture for the YMCA's rock wall project.

Bellingham Technical College is a Washington state higher education institution with a curriculum designed to develop professional skills in students so they are viable in the workplace. The welding program is set in a full-scale welding shop. Training ranges from specialty courses to a two-year welding technology applied science degree.

Mondau approached her group of 55 predominantly male student welders, looking for five or six volunteers for the rock wall project. Immediately the "Welding Chicks," a group of female welders, stepped forward to take on the assignment.

The YMCA project provided an opportunity for the women welders to apply their skills and expertise in the real world. The initial project entailed welding in the steel framework for the climbing wall, which would cover a vertical face 24 ft. wide by 31 ft. tall. Vertical, horizontal, and diagonal I-beams measuring 12 in. comprised the existing building steel.

The project entailed welding in 4- by 11/2- by 1/4-in. channel in horizontal runs at approximately 5-ft. intervals and then tying in eight vertical 11/2- by 11/2-in. Unistruts that were 31 ft. long on 42-in. centers.

"We gals had studied welding and metallurgy theory; we had logged many hours of time under the hood; and we had progressed well with our certifications," Boxx said. "This project enabled us to document that we could jump out of the nest and fly."

Through this project, the women learned about the differences between welding in the shop versus working in the field. They quickly became aware of new challenges in the field, such as safety, equipment setup, logistics, and how to interface with other crews in a dynamic environment.

"You get pretty comfortable in the shop, so when you're in the field, you have to deal with a lot of variables," said Wicklund.

"There's always a little bit of troubleshooting when getting set up in the field," Boxx said. She also noted that working on scaffolding or tied off to building steel created a new set of considerations when planning and executing numerous tasks.

Communication was key to working with the scaffolding with welders at different levels, according to Mondau.

"They were communicating a lot to let the other women know when they were hoisting steel and when they were about to strike an arc," she said.

And as they worked, the women welders threw in another variable: working with fellow welding student Colin Elenbaas so he also could gain some field welding experience.

One hundred fifty hours later, the welding machines were switched off, and the project was declared a done deal. The students had planned ahead, were well-organized, functioned together as a team, enjoyed one another's company, and completed the job at a professional level. They packed up their gear and left the area in order, their rigs rumbling back to the college.

Rock panels then were bolted to the superstructure, a job that was completed easily because of the quality of the work.

"The welding and fabrication were world-class, so our assembly operation went smoothly," Harding said.

Women Welders Revisited

However, another complication arose. The master plan called for a belay bar above and spanning the width of the wall. The belay bar was necessary to provide the climbers with a safety tie-off, and the wall couldn't be used until it was installed and functional.

Mondau, Harding, and I climbed to the top to locate attachment points in the building steel, determined the configuration of the brackets, and factored in a bend in the belay bar to address the folds of the rock face.

Two parallel 12- by 4-in. I-beams were situated in the building framework, from which six trussed and cantilevered brackets could be suspended. Dimensions were taken and drawings were rendered. The brackets were spec'ed for 3-in. channel. The horizontal belay bar was 2-in.-ID Schedule 40 pipe that was 24 ft. long. The drawings were sent to a mechanical engineer, who had firsthand knowledge of the building and the requirements, for approval.

And once again, the students saddled up their fastest horses and proceeded to ride back into combat, so to speak.

"This project was a blue-sky job reaching into the stratosphere, and I wanted to volunteer as a leader this time," Adam said.

She and former crew leader Boxx agreed that although the second part of the project was shorter, they both had to complete the same types of duties when leading the welders.

"It's pretty straightforward project management—getting your dimensions, cutting your material, and matching your talents with the tasks," Boxx said.

This second phase of the project followed the first by about four weeks, so the team makeup was modified because several of the original crew members were slated for certification testing at the college. Wyatt Myiow and Jermiah Cooper signed up for the job with Adam and her teammates.

As during the first phase, the students realized that one of the biggest challenges was adjusting to the differences between welding in a booth and in the field.

"In our classes, you spend a lot of time welding in your booth—sometimes three hours at a time," Kuebelbeck said. "In the field, you have to be systematic about what you do, and you have to communicate with people."

Another challenge was one that the women—students and instructor alike—always keep in mind.

"You have to be as good as or better than the men or you won't make it," Mondau said.

But after 70 hours, challenges aside, it all came together: The belay bar was installed and ready for final inspection and testing.

With another project completed successfully, the students left with a feeling that they not only learned a lot about welding and fabrication, but also helped the community with their time and skills.

"To be able to contribute to the community means a lot," Boxx said.

Jer Mondau, Instructor

|

- Has been employed as a welder and fitter in Whatcom County for 26 years

- Has been a welding instructor at Bellingham Technical College since 1995

- Is certified in SMAW 7018, FCAW, and aluminum GMAW

- Is a certified welding inspector

- Received a Community and Technical Colleges Vocational Technical Education Certificate, 1995

- Graduated from Bellingham Vocational Technical Institute as a certified welder, 1976

- Graduated from Mount Baker High School, Deming, Wash., 1975

"I first began welding in 1976, and from the moment that first arc was struck, I knew that metal—not wood, with its spiders—was the road for me. I began the trek as a certified welder and I'm now both a welding technology instructor and an AWS-certified welding inspector. Through my long relationship with metal and fire, I have learned the intricacies of my craft and am now able to coax my visions of grace and form from the hard, frequently stubborn metals I've learned to love. In my art, I strive to combine the rich appeal of metal and mixed media in a functional way. I find great comfort, artisitic stimulation, and sheer excitement in discovering the secrets metal holds for me."

Cheryl Boxx, 39

|

- Bellingham native

- Diploma, desktop publishing, Seattle Art Institute, 1997; B.A. in parks and recreation, Western Washington University, 1987

- Has worked primarily in manufacturing industries for high-end, specialty outdoor equipment

- After being laid off, joined the Dislocated Worker Program and studied welding for artistic purposes at Bellingham Technical College

- Helped create Delilah, a permanent sculpture for the Bellingham Public Library

- Currently works as a custom manufacturer and welding artist

- Was on a team that custom-fabricated a 14-ft.-tall steel and cast-iron sculpture designed by Joyce Kohl and installed at the DuPont, Wash., Sound Transit terminal, 2003

"To be able to contribute to the community means a lot."

Angel Adam, 25

|

- Bellingham native

- Graduated from Lynden High School

- Worked in a family business for seven years, making custom canvas for boats, cars, furniture, and airplanes. After the business was sold, she entered a Dislocated Worker Program and decided to take welding to broaden her creative abilities.

"I really would like to do more in the artistic side of welding, so I want to get into art. I want to be able to draw something and weld it."

Tiana Wicklund, 21

|

- Bellingham native

- Graduated from Sehome High School, 2000

- Worked full-time at D-Tech Burglar and Fire Systems

- Is an AutoCAD® drafter

- Is a full-time student at Bellingham Technical College

- Plans to attend Diver Institute of Technology (DIT) in Seattle after graduation to become an underwater welder

"Welding has been a great experience. I'm kind of a Renaissance woman, so this is something else to add to that. I'd like to continue in my welding certification."

Mary Kuebelbeck, 40

|

- Born in Midwest, Minn.

- Spent 10 years in British Columbia in advertising photography

- Went to Bellingham in 1992 and found welded sculpture at Big Rock Garden. "I knew I needed to create with metal."

- Currently has metal sculpture on display at Peace Arch Park, Wescott Reserve, and Civic Sculpture Exhibit at Bellingham Public Library

- Currently working with an all-women group, Roadside Studios, in Mount Vernon

"Welding is a means to an end for me. I want to build things, be a blueprint reader, and get into metallurgy."

Jer Mondau, who contributed to this article, has been employed as a certified welder and fitter in Whatcom County, Wash., for 26 years. She is a certified welding inspector and a welding technology instructor at Bellingham Technical College, 3028 Lindbergh Ave., Bellingham, WA 98225, 360-738-3105, www.beltc. ctc.edu. She and Hollingsworth were project coordinators for this project.

Airgas Inc., 259 N. Radnor-Chester Road, Suite 100, Radnor, PA 19087, 610-687-5253, fax 610-687-1052, www.airgas.com.

Entre Prises Climbing Walls, 20512 Nels Anderson Place, Bldg 1, Bend, OR 97701, 800-580-5463, www.epusa.com.

The Lincoln Electric Co., 22801 St. Clair Ave., Cleveland, OH 44117, 216-481-8100, fax 216-486-1751, www.lincolnelectric.com.

Miller Electric Mfg. Co., 1635 W. Spencer St., P.O. Box 1079, Appleton, WI 54912-1079, 920-734-9821, www.MillerWelds.com.

About the Author

Bob Hollingsworth

About the Publication

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Welder, formerly known as Practical Welding Today, is a showcase of the real people who make the products we use and work with every day. This magazine has served the welding community in North America well for more than 20 years.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Sheffield Forgemasters makes global leap in welding technology

Welding student from Utah to represent the U.S. at WorldSkills 2024

Lincoln Electric announces executive appointments

Lincoln Electric acquires RedViking

Engine-driven welding machines include integrated air compressors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI