Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Getting it there yesterday

Greenheck Fan cuts lead-time to, in some cases, mere hours

- By Tim Heston

- November 25, 2008

- Article

- Shop Management

The sheet metal fabricator produces various air-movement products, from bathroom exhaust fans, dampers, louvers, and general-purpose fans to complete air-movement systems for commercial structures. For most products, customers can place an order and receive a custom fabrication within three to five days, and sometimes in less than 24 hours.

Short lead-times didn't come about through one machine or software package. Instead, managers set out to change a combination of things over a period of years: an innovative corporate structure, custom automation, and information technology connecting it all together.

Corporate Structure

In 1947, the year of its founding, Greenheck had three employees producing $3,500 in annual sales in a 3,000-square-foot facility. Today the company is a giant in Schofield, Wis., employing more than 2,000 who work in more than 2 million sq. ft. of manufacturing space (see Figures 1 and 2).

Between its founding and the early 1990s, the company worked within a typical corporate structure, with vice presidents over various business functions: VP of manufacturing, VP of engineering, VP of sales and marketing, and so on. But within the past few decades, managers recognized the structure could stifle growth, foster a silo mentality, and hamper collaboration.

Now the company is organized by product divisions: one for outdoor air products and whole-building ventilation; another for air control architectural products, including dampers and louvers; and a third for air-movement products that run the gamut from small bathroom fans to immense industrial air-movement systems (see Figure 3). Each division has a general manager who supervises the sales and marketing, engineering, and manufacturing for the product groups. This structure, sources said, focuses everything on the products' design and service, and drives away the turf wars that can permeate large manufacturers.

"This was really a driving force to make our products more competitive,"recalled Jared Wesenick, manager of the company's Machine Development Center.

Manufacturing Automation

Wesenick works for one of the company's departments that serves all product lines—and it's an important department (see Figure 4). Bob Greenheck, one of the firm's founders, is an engineer who loves to tinker with and build machines, and the culture continues today. The company builds many of its machines in-house. Greenheck's Machine Development Center receives RFQs from the three divisions. Then Wesenick's team tries to find an off-the-shelf unit or one customized to fit Greenheck's needs. If none is available, the department designs a machine, determines its payback (the target usually is three years), and, with management's approval, builds it.

The center's machine designers are brought in during a product's conceptual phase to give input and options, and they're also called upon for productivity and capacity improvement initiatives. Often a project in one area bleeds into others. Wesenick recalled one RFQ for an automated welding operation for a stainless steel kitchen hood. The process began as a productivity improvement initiative to eliminate tedious, time-consuming hand grinding. But to do this required not only a new welding setup, but also an entirely new product design.

"I can't give many details,"he said, "but it's a proprietary arc welding system that doesn't require any postwelding operations. I worked very closely on this project with the product and manufacturing engineers. It involved a complete redesign of a product to take advantage of a process developed in-house."

According to Principal Manufacturing Engineer Bruce Bohr, the custom system develops a corner butt- joint weld that, for all intents and purposes, is cosmetically perfect. "The fit-up is critical as well as the weld quality,"he said. "It's pre-polished material, so we didn't want to work on the weld and have to repolish the whole hood. It is very important the weld is cosmetically correct when it comes out of the machine."

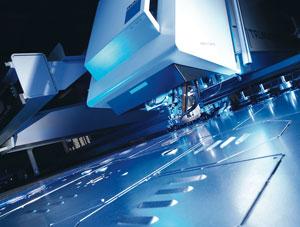

Figure 2: The plant floor, with minimal work-in-process and synchronized production, looks a lot different than it did a dozen years ago.

Welding is only one piece of the puzzle, of course. The entire manufacturing process looks little like it did a dozen years ago. Back then paper orders were sent three or four times a day to the blanking area, where operators manually created a nest of rectangles, a procedure that alone took an hour or two. The blanks then traveled to the layout area, where workers marked where holes, notches, and bend lines would go, before moving on to punching and notching machines, then on to the press brakes. Operators wrote the bending program at the machine, programmed the backgauge, and bent parts. The batch moved on to manual welding operations, then finishing, and finally assembly. A single kitchen hood had up to 50 parts.

Today the order arrives to the shop floor digitally, automatically entering Magestic Systems' TruNEST™ software, which generates nested programs for laser-cut parts. The nesting program generates labels that show exactly where the part is to go. After the laser cuts the blank and necessary holes, the part moves to the press brake where the operator pulls up a library of programs.

As Bohr explained, "[The kitchen hood] is a parametric product, meaning we can use a small library of bend programs to bend a great variety of parts."In other words, part size and geometry may differ, but the parts share many bend sequences and ram moves.

After this, the hood goes into the automated weld system, then assembly and shipping.

The automation has helped cut lead-time from weeks to just three to five days, and this is only for kitchen hoods. Some fan products go through proprietary coil cut-to-length and blanking systems that shave manufacturing time to hours. For certain products, a customer can place a custom order at 11 a.m. and have it shipped the next morning.

Such turnaround, though, couldn't have happened with machine automation alone.

IT Productivity

Of the 35 people in the Machine Development Center under Wesenick, one officially doesn't report to him. He's not a mechanical engineer, nor does he have extensive education in machine design, yet his work is becoming more important as the company continues reducing lead-times.

He works in IT.

Wesenick concedes that it wasn't the easiest task to get an information technology expert on the shop floor; it took more than a year for upper management to buy into the idea. Once they did, the company reaped the benefits.

"We had some electrical technicians in our department who are very good with machine controls,"Wesenick recalled, "including Allen-Bradley, GE Fanuc, our PLCs, as well as some rebuilt systems we use. But they weren't up to speed on our ERP process."

Figure 4: Greenheck’s Machine Development Center builds most of the company’s manufacturing equipment.

That's where IT comes into play. Greenheck has an enterprise resource planning system augmented with software that automates a large portion of all front-end sales and engineering. What makes Greenheck's system unusual is how completely it penetrates the organization, all the way down to the machine controllers. The controllers serve as the end point for a chain of events that start with a customer logging on to a Web site and placing an order.

This is part of a concept the company calls "field to factory,"or F2F. Here's the idea: A customer in the field can place an order online that, within hours, triggers the blanking systems on the factory floor. Within minutes parts are nested and put in the queue for blanking. Within hours the parts are ready for final assembly and shipping.

Several IT elements make F2F happen. First is the company's CAPS, or computer-aided product selection, system. Customers access CAPS through an online interface, where they are asked basic questions about a product's use. For example, for a fan the system asks the room size and the kind of facility it's for, be it a school, office, industrial facility, hospital, or residence. From these and other basic questions the software figures how many cubic feet of air needs to be moved and sizes the fan accordingly.

The company developed its first CAPS system in-house and this year moved the system to Cincom's Socrates®, a commercially available platform. The software uses a parametric template that takes specific measurements—say, a duct needs to be 16 by 18 inches—and filters it through various constraints. Based on measurements and some fundamental application information, the software goes through a process of elimination, identifying what a design can't be first and then determining the best parameters from the remaining alternatives.

David Loomans, the company's IT guru, is one of the systems' principal architects. "This used to be a manual process,"he recalled. "People had to look at fan curves in a catalog [to determine the required CFH and fan size] and do it all by hand."

Once CAPS completes its work, it sends information through translation software to SAP's Product Configurator, which works with what's called a super bill of material. These super BOMs contain material information for every variation of a particular product. Based on input variables from CAPS, the Product Configurator selects the proper items from the super BOM and sends them down to manufacturing.

From here the data is transferred to another software product called SAP MII (Manufacturing Integration and Intelligence), which sends information down to the machine controllers. Operators don't have to scan or key in anything on the floor; the ERP system links seamlessly with shop floor machines using OPC, or open process control. "We use OPC technology to get right down to the SCADA level and into the machine controller itself,"explained Loomans. (Because the IT manager has become so engrossed in SAP initiatives, he recently adopted the job title of SAP project manager.)

As to what happens next, Loomans described an order for dampers. "We have several [coil] cut-to-length and punching machines that are all synchronized. With the order in hand, the machine controllers know they need to make the frame, the blade, the jamb seals, and the closure strips. The machines blank everything the damper needs in a synchronized manner."The result: All parts for each damper arrive at the assembly area at once for assembly.

For certain products IT takes engineering automation a step further. For some laser-cut components, "we send the characteristics from SAP into CAD software, and we generate CAD dynamically,"Loomans explained. "Then we send that CAD directly to the laser."

Portions of the manufacturing floor resemble an airport terminal, with large overhead monitors showing job statuses. Because manufacturing is synchronized, the floor lacks the typical stacks of work-in-process, a notable feat considering the high-mix, low-volume environment. The manufacturer processes many tons of material a month, but lot sizes of five or fewer aren't uncommon.

Greenheck's engineers previously spent their days on rote calculations—but not anymore. The rote work is automated, and engineers spend their time on highly complex work that simply can't be automated.

Next Steps

Greenheck has been lucky enough to skirt the real estate mess; the company sells mostly to commercial and industrial customers. "We're worried about it, of course,"Loomans said, "but at this point we haven't been affected by it yet."Regardless, he said, buildings will still require air-movement products, no matter what happens on Wall Street, and quick turnaround helps Greenheck win business.

Next steps will include integrating automatic supplier communication. The company already replenishes material using a lean manufacturing kanban system. Coils feeding the blanking lines, for instance, are automatically replenished once they reach a certain point.

But Loomans hopes to take this to the next level and communicate with all suppliers using EDI, or electronic data interchange, tools. "We've got some EDI and supplier information flowing currently,"he said. "We're in the middle of our second wave of [IT] implementation. The next step will be getting better information to our suppliers."

Managers noted, however, that the company didn't get to where it is through one whiz-bang product. Buying only automated equipment or only software wouldn't have made the same impact on lead-times, they said.

What was necessary was the change in corporate structure and a culture that focused on product improvement, not one department's turf. Change happens slowly when turf wars get in the way, and according to sources, Greenheck has been lucky enough to avoid these turf wars entirely.

"That's really been the culture as long as I've been with the company, now 13 years,"Wesenick said. "We've never had those silos to break down."

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI