President

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Advanced roll forming troubleshooting

Avoiding potential problems in the machine, material, and tooling

- By Steve Ebel

- February 27, 2003

- Article

- Roll Forming

|

If the tooling is fine, you need to begin by dividing the process into three areas:

- The roll form machine

- The material being roll formed

- The setup of the roll form tooling

Then start eliminating the areas as potential causes of the problem.

Machine Face Alignment

One of the most neglected areas of a roll forming line is the machine face alignment. It doesn't matter how well the tooling is built and designed or how good the quality of the steel being roll formed is ... if the alignment is bad, the product will be bad.

|

| Figure 1. A quick check with a straight edge on the roll form tooling can indicate a problem with machine face alignment. |

Many times a quick check with a straight edge on the tooling can tell you if there is a problem (see Figure 1). If you find a problem, you must remove the tooling and align the machine face.

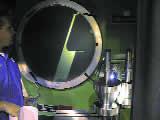

The first step in doing a machine face alignment is to check the shafts to make sure they are not loose or have bad bearings. If they are, you'll need to tighten or fix them (see Figure 2).

The next step is to remount the outboard stands and set the top shafts parallel to the bottom shafts. This can be done with calipers, a large micrometer, or machine face alignment rolls.

When all the top shafts are parallel with the bottom shafts, use a straight edge to align all the bottom shafts to each other, keeping them within 0.005 inch station to station.

|

| Figure 2. The first step in doing a machine face alignment is to check the shafts to make sure they are not loose or have bad bearings. |

When all the bottom shafts are aligned to each other, use a smaller straight edge from the bottom shaft to the top shaft to align them to within 0.002 in.

Material Conditions

The condition of the raw material also can affect the quality of the final product.

Material thickness variation may occur within the same coil from one end to the other. When it varies from one edge to the other edge, it is called crown. This is a smooth curve of consistent variation in thickness.

|

| Figure 3. When a coil with crown is slit into mults, the result is two wedge-shaped coils, one thicker than the other. |

Usually master mill coils are slit into narrower widths called mults. If the coil has crown, the result of the slitting is two wedge–shaped coils (see Figure 3). The one from the center of the master coil will be thicker than the one from the edge of the coil. Mults from a crowned coil also are cambered, which means one coil is longer on the left, while the other is longer on the right.

Mill coils with edge wave, then slit into narrow mults, show random camber in the outer strands-first in one direction and then the other. It is impossible to adjust for camber that varies throughout the mults. If the coil has continuous camber in only one direction, twist and sweep will be problems during the roll forming process.

|

| Figure 4. Coil set and cross break may occur if support rolls aren't used at the exit of the straightener, leveller, or feed device. |

Coil set and cross break may occur if support rolls of the proper configuration are not used at the exit of a material straightener, leveler, or entering feed device (see Figure 4). Without the support rolls, the strip breaks harder over the entrance rolls or exit rolls, creating these conditions.

Another dimensional variation is crossbow. This condition may occur during the coiling process at the mill or slitter and is caused by an incorrect slitter setup. With crossbow, the top surface of the material, edge to edge, is not equal in length to the bottom surface. The shorter surface is inside of the radius.

Forcing material with coil set and crossbow to lie flat will cause oil canning, which means the center of the strip will be longer than the edges. Forcing the material in the opposite direction will cause edge wave.

Tooling Setup

The third area to examine is the tooling setup.

You should document setups so they can be repeated as closely as possible each time the tooling is put onto the roll forming machine. One way to do this is to record the flange or hub settings between the rolls with the material in the tooling.

|

| Figure 5. An inspection mirror and flashlight can help you look for gaps or see if the tooling is down, touching the material. |

Keep the roll form machine and tooling clean and free of any grit or material that may change tooling alignment from top to bottom. Wipe the spacers, shafts, and tooling clean before installation.

The roll form tooling should be producing the desired cross section before the straightener is mounted. If the cross section is not to print, remove the straightener and adjust it before remounting.

Roll form tooling that is set up properly will produce a symmetrically shaped part that does not twist.

Tricks of the Trade

|

| Figure 6. An optical comparator compares the actual roll form tooling to the original design. |

Following are some helpful hints that can be used during the troubleshooting of roll form tooling:

- Use an inspection mirror and flashlight to look for gaps or to see if the roll form tooling is down, touching the material (see Figure 5). In these cases, compare the roll design to the actual rolls to ensure they are accurate.

- Backing up the roll former can allow you to look for pressure marks, misalignment problems in a radius, or roll stops that are being hit too hard.

- Using a straight edge on the back side of the roll form tooling will indicate machine face alignment problems and will show if the top roll form tooling is parallel with the bottom roll form tooling.

- If you can't check the roll tooling with a straight edge, smear grease or heavy oil onto the material and run it through each pass of the roll form tooling. If the grease is heavier on one side of rolls than the other, the top rolls might not be parallel with the bottom rolls.

- If the problem seems to be isolated to one particular pass, cut the material on either side of the pass and raise the roll tooling so that you can remove the material and inspect it for problems.

- When you can't isolate the problem, remove the straightener, and then remove one pass at a time. Inspecting the part out of each pass as you remove another will help you isolate the problem.

- Once you isolate the problem pass, set up the pass in an optical comparator and compare it to the tooling design (see Figure 6). It helps if you can enlarge the tooling designs to the magnification of the comparator so an overlay can be done.

- Wire the problem pass with plug or wire gauges (see Figure 7). The gauges can help you check for loose or tight spots.

|

| Figure 7. Wire gauges passed through a roll form tooling pass can indicate loose or tight spots. |

About the Author

Steve Ebel

1347 Madison

Grand Haven, MI 49417

616–296–0601

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI