CSP

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Addressing behavior-based safety issues

- By Cheryl Henderson

- April 11, 2005

- Article

- Safety

|

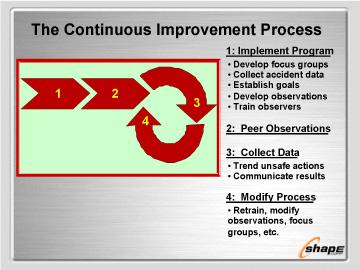

| Figure 1 Courtesy of Shape Corp. |

Nearly every resource for successful safety performance touts the need for management support, first and foremost. Management support clearly is necessary to resolve behavior-based safety problems. However, as we found at the Shape Corp., developing a critical mass of ground support is even more important.

Beginning the Process

Investigating a serious injury, we heard witnesses say that the injured person performed the same task in the same unsafe manner on numerous occasions. Our management team spent many hours trying to solve this surprising finding. Why would co-workers allow the unsafe acts to continue? What would cause an employee to perform a dangerous act repeatedly? How could this act go unnoticed by the leadership team?

|

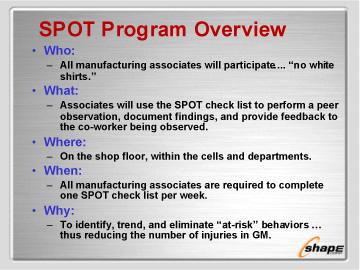

| Figure 2 Courtesy of Shape Corp. |

Using our continuous improvement process (see Figure 1), we surveyed and questioned employees, and then implemented changes intended to encourage open communication among peers and leaders. These efforts resulted in some success.

Safety teams began to work within small groups to reduce ergonomic injuries. This focus brought significant improvements, but the overall success was erratic and depended on the immediate leaders. When production, cost cutting, lean manufacturing, or new-product launches intruded on the teams' efforts, employee priorities changed. Still, all levels of employees recognized the importance of focusing on behavior as well as tools, procedures, and other factors to ensure safety. At last the timing was perfect to make the move from a traditional safety program to a program that focused on identifying and acknowledging safe performance.

Why Unsafe Practices Continue

Our research found that an employee who failed to meet production requirements had a 100 percent chance for disciplinary action. Failure to perform every act safely carried a significantly less than 100 percent chance for disciplinary action — or even injury. Employees believed speaking up to co-workers who were performing tasks unsafely carried a 100 percent risk that the person being coached would not appreciate the interference.

|

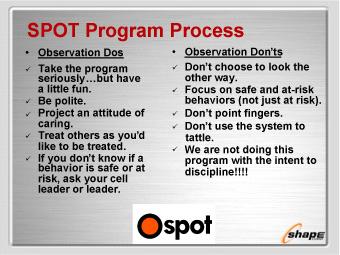

| Figure 3 Courtesy of Shape Corp. |

The Plan

Out of our research grew the Shape Peer Observation Team (SPOT) program (see Figures 2, 3, and 4). A team of hourly associates, nominated by their leaders, met month after month, but with little progress initially. Developing the form and format to perform peer observations was the easy task. Learning to communicate assertively with peers about performance was far more difficult.

It took more that eight months of creative brainstorming and active practice for the team to develop the confidence to test their efforts. During that time the team led activities that ensured behavior was not inhibited by equipment or tools, such as inspecting gloves and other personal protection items.

Our behavior-based safety program was not designed to be a discipline tool. Observations are conducted peer-to-peer, ultimately without consequence for unsafe behaviors by the worker being assessed. The only instance in which associates are required to report directly an observed unsafe behavior to their cell leader or supervisor is if the associate believes the behavior is immediately dangerous to the worker's life or health.

|

| Figure 4 Courtesy of Shape Corp. |

Results were evident almost immediately. Team members were able to see performances at both ends of the safety spectrum. They were able to communicate effectively with most people they observed using the SPOT check list (see Figure 5). Most of all, their successes led to more success. Although it took management's commitment to personnel, training, and time resources, it took the efforts and confidence of the manufacturing associates to achieve a real improvement in safety behavior.

Going forward, SPOT team associates reviewed each unit's safety record and interviewed the management teams before selecting the site for initial implementation. Once the SPOT process was sustainable within the initial unit, the team's activities expanded to other business units until the process was implemented throughout the entire organization.

|

| Figure 5 SPOT Check List: Courtesy of Shape Corp |

Personnel perform SPOT checks weekly to monitor the program's effectiveness. Cells within business units challenge each other, and awards (cookouts or T-shirts) are given when goals are met.

We found that tracking the number of performance checks as part of the performance review encourages conformance to the initiative. We also track safe-behavior percentages. The baseline result for our initial business unit implementation shows that 73 percent of the behaviors are safe. This leading indicator is being used to correlate against the typical trailing indicator—injuries. Improvement goals are developed from the baseline.

Lessons Learned

Our efforts to resolve behavior-based safety issues taught us several valuable lessons. Among them are:

- Use problem solving to determine the root cause of systemic safety problems.

- Engage problematic employees.

- Get rid of excuses; find out and eliminate perceptions that are getting in the way of success, such as wrong equipment and lack of communication.

- Practice patience and be prepared to move quickly when the opportunity arises.

- Communicate, communicate, communicate.

About the Author

Cheryl Henderson

Shape Corporation

616-846-8700

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI