Catalyst

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

12 tips to improve your value stream maps

A VSM is a tool to help eliminate waste, not create it

- By Anthony Manos

- October 20, 2014

- Article

- Shop Management

A value stream map (VSM) is a visual representation of the tasks, value-added and non-value-added, used to generate your product or service from beginning to end, including material and information flow. A VSM will help you create a better future state and operating strategy. A business plan says what, an operating strategy says how.

According to Learning to See, a book by Mike Rother and John Shook, value stream mapping has four steps:

- Determine the product families (or process families).

- Create the current-state map.

- Develop the future-state map.

- Determine the plan.

This seems straightforward, but it’s easy to get lost in the details. A VSM should help your organization develop a plan for action, but without subsequent action, the act of making a VSM is itself muda—waste. The 12 tips here will help you ensure that a VSM isn’t just a waste of time, but instead aid people in your organization to bring about lasting, positive change.

1. Use Proper VSM Conventions and Symbols

Often people call things value stream maps, but they’re not developed, drawn, or acted upon with the correct methodology. They might be value stream maps in spirit, but they do not follow true VSM techniques.

Some might cover an entire wall of a room with brown butcher paper and use color-coded Post-It™ notes for every single step in a process. It’s not long before hundreds of Post-Its cover the wall. It’s impressive. It takes a lot of work, and now they have every step down to the nitty-gritty detail, but it is so overwhelming that they become paralyzed in trying to make any improvements.

The best practice is to draw maps on 11- × 17-in. paper (or A3) using generally accepted standard symbols or icons. By sticking to the standard of symbols, anyone trained in VSM should be able to read your maps.

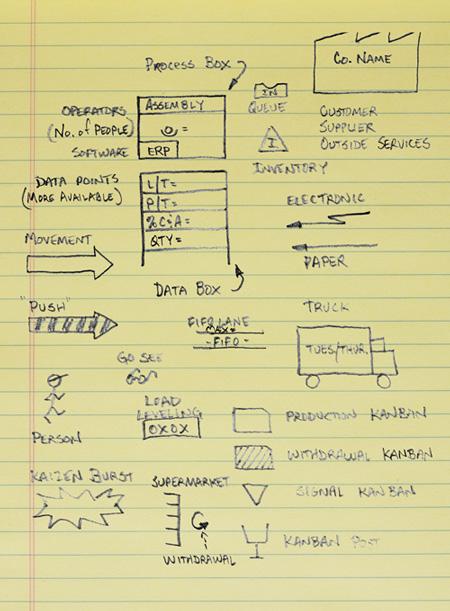

2. Draw It by Hand First

Some VSM software programs help you draw maps and perform many data manipulations. In my opinion, you should learn to draw it by hand first, because it will help you better understand the methodology (see Figure 1). By putting pencil to paper, you emerge yourself in the mapping process, and that’s how it becomes real. Yes, it may seem like a struggle at first, but with practice it becomes easier. The day you can grab a piece of paper, start discussing a problem with a colleague, and draw a map is the day you really start to understand the power of VSM.

Also, maps should be temporary (see tip No. 10). Once you reach your future state, that becomes the current state and you repeat the process of continuous improvement. Paper and pencil allow you to update maps easily, with no overprocessing waste.

Figure 1

By drawing value streams by hand and sticking to the standard symbols, anyone trained in VSM should be able to read your maps.

If you decide to use software instead of paper and pencil, make sure you are using it for the right reasons, such as for the ability to send a map electronically, and not just to make your maps look prettier.

3. Determine the Process Families—aka, Product Families

Many organizations skip this step because they are not sure how to do it, they think their processes are overly simple when they are not, or they think it is too hard to do. Never skip this step. If you do, you may be setting yourself up for future difficulties.

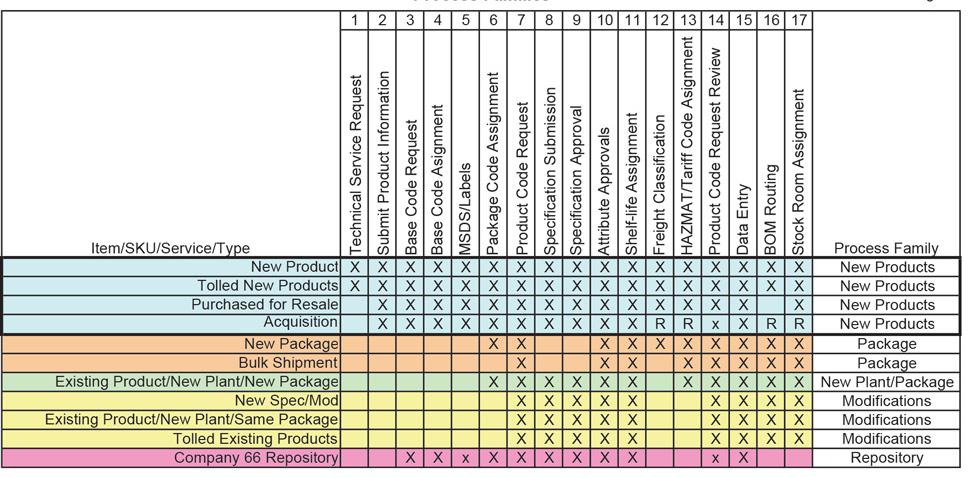

Many job shop managers say they never make the same thing twice. This might be true, but they probably fabricate items that go through the same or similar processing steps. This is why, instead of product family, I like to use the term process family, which also makes it easier to apply to office functions (see Figure 2).

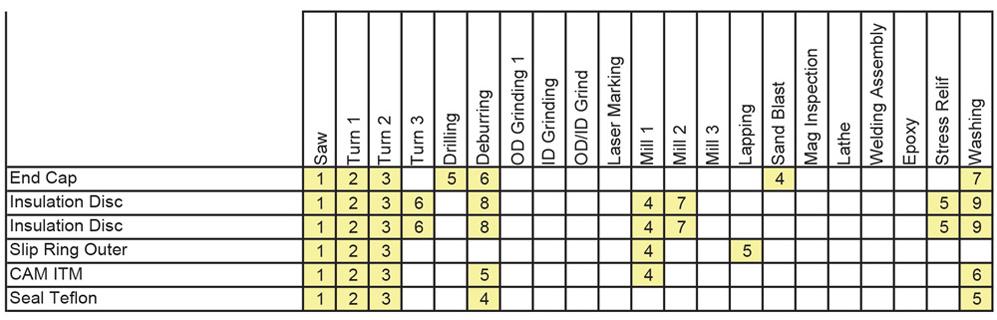

By grouping jobs into different process families, you can achieve better flow and overall improvement in a job shop environment. For instance, an improvement team at one high-product-mix machine shop wrote the number sequence of process steps as that particular part went through the shop. From there they determined that there was an even better sequence of operations, and that combining some operations would make it easier to produce the part at a lower cost than originally quoted. From that point on, when they prepared a quote, they made sure to review their process family matrix to ensure they had the best order of operations (see Figure 3).

4. Limit the Number of Process Boxes

When you create your process family matrix, try to keep it at the appropriate level or scope. Limit the VSM to between 10 and 15 steps. Detailing more than 15 steps may make it too complicated.

VSM is scalable, so one process of your door-to-door map (showing everything from the initial order through shipping and receiving payment for that order) still should have only 10 to 15 steps. One of those steps may be “fabricating.” This can be broken up into another departmental-level map that also may have10 to 15 steps: laser cutting, bending, hardware, welding, and so forth. If a map has more than 15 steps, you might want to consider combining steps and renaming the process.

5. Use a Team to Create the Maps and a Plan

Having one person create the map means you used only one brain and two hands. The information gathered may be biased or, even worse, incorrect. Decisions need to be made for what is best for the entire value stream, and that’s hard to do with only one person. Make sure you use a good cross-functional team to walk the shop floor, analyze part flow, gather the information, and then draw the map.

Ideally, someone with experience in VSM should lead the initial meetings. A person who has drawn several maps can help determine the process families with the team, teach the team the correct way to collect data and information, show how to draw the maps, coach toward a better future state, and facilitate a successful event.

6. Start With Basic Building Blocks

If you’re trying to create a manufacturing cell when basic concepts such as 5S, standard work, or teamwork are not even present in an organization, good luck. I’m not saying that you can’t jump to a more complex technique or practice right away, but you will have a higher probability for success if you have a start on the basic concepts. This also goes for lean concepts like pull systems and kanban as well as total productive maintenance. Start with some of the basic principles and tools first before you try to implement something more complex.

7. Don’t Expect Everything to Show up on the Map

Even though the maps will give you great information and insights for improvement, they typically do not have other enterprisewide initiatives that an organization should undertake during its lean journey, such as 5S workplace organization and standardization. A company needs to have 5S everywhere, and VSMs may show only an area or process that needs 5S, not the entire facility. Also, other important functions like communication and training do not usually show up as an action item on a VSM, but these functions are extremely important while implementing lean concepts.

Figure 2

This process family matrix shows how one operation separated its ERP coding duties in the front office into process families, identifying each process family with a different color.

8. Appoint a Value Stream Manager

The value stream manager should ensure that the organization implements the plan to attain the future state. Such a manager can see the whole value stream and work with teams to implement the plan. If you do not appoint the appropriate person as value stream manager, the maps and plans may languish in the ether.

9. Follow the Plan

A company might take all the time and trouble to create the plan—and then fail to implement it. What a waste! Managers at one company created their plan and decided to do other things that popped up during the next six months. They stayed in their old mode of firefighting instead of using the plan to improve the value stream. They even decided to redecorate the office (not on the plan) with new furniture instead of focusing on more important projects. Creating the plan isn’t the most important thing—implementing that plan is.

10. Update the Maps

One of my favorite questions I received while presenting at a conference was “How often should we be updating our maps?” I replied, “Basically, whenever there is a change, probably once a month or so.” There was a long pause and then the person said, “I guess we are a little behind.” I asked, “When was the last time you updated your map?” He said, “Two years ago.”

Obviously, you need to keep the maps updated, and it’s easy to do if you use paper and pencil. We use these maps to communicate. If you don’t show your progress, you are not communicating effectively.

11. Post Maps Where People Will See Them

Question: “Where are your maps?” Wrong answer: “In my desk drawer.” Correct answer: “Posted on our lean communication board.”

Don’t hide your maps. A key benefit of displaying your value stream maps is to communicate what is going to happen at your organization over the next few months or during the next year. Many people resist change because they fear the unknown. Posting the maps with the plan removes or eliminates this fear. It’s also a way to start discussions and obtain buy-in and ideas for improvement. Don’t hide your maps; be proud of them!

12. Start With the Big Picture

Begin with a door-to-door VSM of one of your process families. Try not to dive into a departmental or cross-functional map before developing the higher-level map. By seeing the big picture, you will be able to make better decisions about your value stream. If you dive into a lower-level VSM, you may not get the results you were hoping for.

This goes hand in hand with No. 4, limiting the number of process boxes. If you initially draw a giant map (especially as described in No. 1), you can get lost in detail and focus on elements that may not have a dramatic effect on overall efficiency.

The massive map may, for example, uncover problems with welding fixtures. That’s fine, but a door-to-door map—one that identifies welding as part of the “fabrication” step—shows a different story. The map reveals that fabrication takes five days, but order entry and engineering takes 10 days. The broader map shows where to start—in this case, order entry and engineering. Drawing a detailed map here will probably reveal significant waste, and show you where you will get the biggest bang for your improvement buck.

Eliminate Waste, Don’t Create It

When it comes to VSM, people often become so enamored with their own bureaucracy or analysis that they are just wasting valuable resources, especially time. I’m talking about the people who spend too much time making fancy graphs from the data that was collected, or the ones that want to get the data down to the one-hundredth decimal point. Remember what you are trying to do here: eliminate waste, not create more.

Figure 3

This process family matrix (simplified from a more comprehensive example) groups different jobs that require similar proc-esses, which can become the basis for a value stream map. This shows a machine shop operation, but a similar matrix can be drawn for sheet metal fabrication. The operation may produce diverse parts, but many share similar process steps, such as laser cutting, bending, and hardware insertion.

References

Chet Marchwinski and John Shook, eds., Lean Lexicon: A Graphical Glossary for Lean Thinkers, 5th ed. (Cambridge, Mass.: The Lean Enterprise Institute, 2008).

John Shook and Mike Rother, Learning to See: Value Stream Mapping to Add Value and Eliminate Muda (Cambridge, Mass.: The Lean Enterprise Institute, 1999).

Beau Keyte and Drew Locher, The Complete Lean Enterprise: Value Stream Mapping for Administrative and Office Processes (New York: Productivity Press, 2004).

Karen Martin and Mike Osterling, Value Stream Mapping: How to Visualize Work and Align Leadership for Organizational Transformation (New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2014).

About the Author

Anthony Manos

9270 Corsair Road, Suite 18

Frankfort, IL 60423

815-469-5678

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI