Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Continuous improvement, from the first quote to the final shipment

How one fabricator works to improve the entire manufacturing cycle

- By Tim Heston

- April 1, 2015

- Article

- Shop Management

Figure 1

This automated shearing, punching, and bending center

combines several operations in one machine.

A veteran press brake operator at Skilcraft LLC recalled his first day on the job. He arrived at the fabricator several decades ago, and even at that time he wasn’t a rookie; he came to the Burlington, Ky., company from another sheet metal shop in the area. On his first day, one of Skilcraft’s founders came out to the floor, took a look at the pieces he was forming, and measured them. They were off by a few thousandths, well within the customer’s specified tolerances.

“But it wasn’t to the founder’s liking, so he threw the pieces in the scrap bin.”

So said John Zurborg, company president. High standards have pervaded the organization since six brothers launched it in 1965 as a custom fabricator serving the commercial kitchen business. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the company started to enter new markets as commercial kitchen equipment became more standardized.

The brothers adopted new technology early, and they embraced automation. In the 1980s the company became one of the first fabricators in the area to offer laser cutting, being a beta test site for nearby Cincinnati Incorporated. Several years before they retired in 2004 and sold the company to Skilcraft’s current owners—an equity group headed by Jay Vierling of AEV Capital—one of the brothers, Ronald Anderson, along with CEO Jim Berding invested in a Salvagnini system that incorporates shearing, punching, and panel bending with an 11-inch throat (see Figures 1 and 2).

The Anderson brothers also had an insatiable entrepreneurial spirit. Over the decades they founded and spun off a variety of other businesses. “For instance, they spun off a banking equipment business that turned out to be incredibly successful,” Zurborg said, adding that their accomplishments prove just how effective a job creator manufacturing can be.

Zurborg has a unique perspective. He worked at Skilcraft between 1999 and 2002, left for another opportunity, then returned five years ago. In 1999 the company basically still operated like a job shop—common for many precision fabricators at the time. If a request for quote (RFQ) came in for a blanket order of 5,000 parts a year, estimators prepared a quote for 5,000 pieces. If they won the job, the work order was sent to the floor to be fabricated—the entire order. It didn’t matter if the customer didn’t need all the parts at once.

Since 2004, though, Skilcraft has transitioned away from being a job shop and toward contract fabrication. When customers need 5,000 pieces today, estimators ask how many are needed at a time. But that change really just scratches the surface. Over the past decade, and especially during the past five years, the fabricator’s 80 employees have scrutinized every aspect of the business, from business planning and quoting to assembly and shipping.

The company has enjoyed 20 percent year-over-year revenue growth during the past five years, and this isn’t measured from a low point during the Great Recession. In fact, thanks to government-related work (specifically, enclosures for a secure file cabinet used in government facilities), Skilcraft’s revenue dropped only about 15 percent between 2009 and 2010. This year, Zurborg said, managers expect the company to earn more than two and a half times what it did a decade ago.

Process automation has helped Skilcraft achieve this, as has visual management and new software that continually updates comprehensive metrics. The company’s lean practices, including regular kaizen events, have played a big role too. But as managers described it, they’re all just pieces of a puzzle. It’s the whole puzzle that really matters.

What Company Do We Want to Be?

Zurborg participates in a user group organized by the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association International (FMA). The group consists of shop managers who work in noncompeting fabricating companies from various areas of the country. Some managers in that group tackle customer diversification by growing the number of active customers they have. If one customer should fall on hard times, the fab shop’s top line would take a hit, but revenue wouldn’t fall off a cliff.

Figure 2

Skilcraft’s automated shearing, punching, and bending center incorporates a panel bender with a throat that’s 11 in. deep.

Skilcraft, however, has taken a different approach. Five years ago the company had about 150 active customers. After the recession, company leaders implemented a significant strategic change. As Zurborg recalled, “We all asked, ‘Who do we want to be, and what are our strengths?’” In the ensuing years, the company actually trimmed its customer base to only 35 core contracts.

Culled from the customer base were those that needed services outside the fabricator’s core capabilities, and those that didn’t provide sufficient annual sales volume. (Individual order quantities weren’t considered, because the company’s operations, with flexible tooling and quick changeover, are refined to deliver low quantities of various parts, delivered to the customer as needed.)

For customers that didn’t fit Skilcraft’s core competencies, the sales team helped them find other job shops or contract manufacturers that could better meet their needs. “It’s the path we decided to take, but it doesn’t mean it’s the right path for everybody,” Zurborg conceded.

He also conceded that the strategy was difficult for everyone to accept at first. After all, didn’t those 120 customers provide healthy diversity? Moreover, some culled from the customer base provided low-volume but very profitable work; why walk away from that?

Managers countered that argument in several ways. First, focusing on a core group of customers helped Skilcraft better serve them and streamline operations around their needs. Second, it allowed the sales team to focus on relatively large contract work. If one contract should stop, there’s a good chance the sales team would be able to fill that work with another large contract. This strategy also has been largely responsible for the shop’s 20 percent year-over-year growth.

Third, although the shop has only 35 active customers, they are spread across a variety of sectors, each with different business cycles, and each contributes a good percentage to the top line. In some respects, this allows Skilcraft to have lower revenue concentration than many of its peers. Respondents to FMA’s “2014 Financial Ratios & Operational Benchmarking Survey” said that, on average, between four and five customers make up more than 50 percent of their shop’s revenue. A typical fabricator may have hundreds of customers, but only a few provide the majority of sales.

Finally, margins aren’t immutable. If you shorten overall manufacturing time, from initial order to final delivery, you add capacity while using little or no extra resources. If you fill that capacity with more work, you increase your sales more than you increase your costs. In other words, margins rise. This, sources said, has been the keystone of Skilcraft’s improvement efforts during the past five years.

Four Companies in One

The company has a highly variable product mix. For one job it may cut thousands of pieces on a laser and send them out the door. On another job it may process 600 pieces through cutting, bending, forming, powder coating, and assembly. For some jobs Skilcraft offers vendor-managed inventory (VMI), tapping into their customer’s system and automatically replenishing parts or assemblies as needed. For still other jobs their customer may step out of the manufacturing process entirely and have Skilcraft drop-ship components directly to distributors.

The company organizes work into four business groups: commercial OEM, medical, power generation and aerospace, and government services. This effectively separates the floor into four smaller “shops.” Certain machines, including some laser cutting systems and the automated cutting and bending center, are shared among different groups, and depending on machine load levels, a scheduler may send certain parts for a job to another group. But for the most part, work flows within four separate areas on the floor.

Within each area are parts supermarkets dedicated to certain customers. In lieu of keeping a large finished-goods inventory, Skilcraft offers replenishment programs based on these supermarkets, which hold a controlled amount of work-in-process (WIP). Anyone who retrieves a part from the supermarket triggers an order for the upstream process. It’s a classic pull system of lean manufacturing.

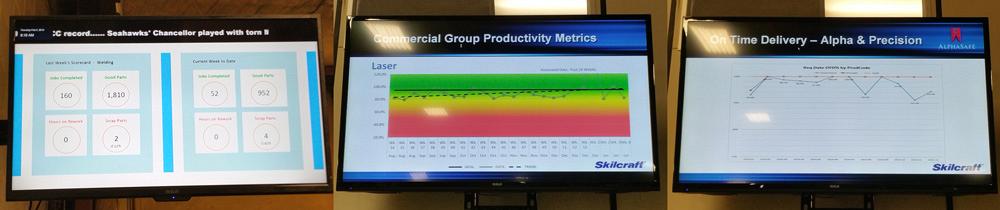

Figure 3

Last year Skilcraft installed monitors on the shop floor, each showing real-time metrics for a particular area. On the left is a “scorecard” for a welding area, showing the number of jobs completed, the number of good parts, the hours of rework, and the number of scrapped parts. The center shows productivity metrics for laser cutting, and the right shows on-time delivery rates.

Faster Fabrication

For years the company’s industrial engineers have worked to shorten manufacturing time. For instance, they have gone outside the traditional precision sheet metal sandbox by adding CNC machining—a previously outsourced process—to mill and turn components for their aerospace customers.

“Our industrial engineer Greg Johnston has analyzed part flow and routings,” Zurborg said. For example, the company’s new lasers are incredibly fast, but they’re not always the best choice, especially if a punch press can eliminate a secondary forming operation.

Similarly, the automated cutting and bending center may be the best choice for many parts, but not for everything. Sometimes parts emerging from the machine need to go to the press brake for one or two remaining bends—say, a series of positive and negative bends not conducive for automated panel bending, or a high flange that’s deeper than the panel bender’s throat. Would it be more efficient to send the part to the laser and then on to the brake for all of its bends? This depends on the part geometry and machine work loads. For the company’s part mix, the automated cutting and bending center is usually faster, but not always.

The fabricator also has worked together with the Kentucky Manufacturing Assistance Center (KMAC), a group that sends lean manufacturing experts to companies across the state. They help organize kaizens, give advice, and, most important, look at the operation with fresh eyes to identify waste. After one meeting, a KMAC consultant noticed that it took a long time for an operator to place a fixture in a certain welding cell. This was (and still is) a complex weldment involving numerous parts, including a lot of spacer brackets.

“After the kaizen event, Greg Johnston, CAD/CAM technician Nick Henderson, and aerospace team member Andrew Bishop came up with an idea for a table with hydraulically actuated hold-down clamps,” Zurborg said, adding that this cut the total welding cycle time by half.

Quoting Strategy

People at Skilcraft had always scrutinized jobs like this at some level, but in recent years they broadened their analyses to include not just the actual metal fabrication, but everything that happens under Skilcraft’s roof, starting at quoting and order processing. Shortening the time it takes to fabricate a part by a few hours or days is always a good thing, but it may not have much of an impact if it still takes days or weeks to quote and process a job in the front office.

“If you asked my quote supervisor, he’d say we quote everything under the sun,” Zurborg said, “but we don’t. We try to be selective in what we quote and try to make sure it fits our capabilities.”

Often the sales team has enough information about a prospect that by the time an RFQ does come along, there’s a good chance the job is a good fit. Regardless, one reason Skilcraft is somewhat selective is that its quotes—input into its Epicor ERP—are comprehensive, using a design and processing template for every component. This includes which processes each component will be routed to, and how long each process will take, using data gathered from similar jobs. For a subassembly that includes several hundred components, this can take a lot of time.

Considering Skilcraft wins 30 percent of its bids on average, is all this effort worth it? “I’ve always argued that it’s just the cost of doing business,” Zurborg said. “And when we win a contract, and we hand it off to the engineering group, the template the quoting group used becomes the template that the engineering group uses. It’s an investment on the quoting side of things, because you don’t win everything, but it saves so much time on the back end for the engineering team.”

“And if you incorporate new software, you make it faster.” So said Thom Kuehneman, the company’s chief operating officer, who described a software investment the fabricator made last year to streamline quoting.

Figure 4

Skilcraft’s assembly areas are designed with flexibility in mind. Stations can be built,

rearranged, transported, and torn down as needed.

Skilcraft contracted with an independent software developer to write a custom, proprietary program that communicates with the company’s main ERP system. Essentially, the software automatically assigns manufacturing processes to a part. This means the quoting technician need only validate that the processes are correct, then plug in the estimated time for each process. It doesn’t automate quoting completely, especially for large assemblies with hundreds of components, but it does shorten the process significantly.

“We’ve tried it on a customer that asked us to quote 600 part numbers, and every one of those parts required laser cutting, forming, welding, and assembly,” Kuehneman said. “Previously it took two people an entire month to develop a quote for such a complex project. With the new tool, they now can get it done in a week.”

Order Processing

While it’s true that comprehensive quoting helps streamline engineering and order processing, front-office operations still are ripe for improvement. When Kuehneman and his team developed a value-stream map for certain product families, they saw how fast manufacturing had become, but the time spent processing that order in the front office really stuck out.

On average, it took 11 days for a new purchase order to make it to the shop floor.

To tackle this problem, Kuehneman’s team mapped the front-office processes. They found that much of that time was taken up by simply copying and distributing paperwork. A complex job can have literally hundreds of travelers attached to hundreds of parts, each with unique routings.

Walking to and from machines on the shop floor is a classic “excess movement” waste in lean manufacturing, but this same waste applies to front-office work. After some observation, the team found that engineers processing work orders spent much of their day walking back and forth to copiers and document scanners. So managers implemented the obvious, low-hanging-fruit improvement: They moved the copiers and scanners closer to the engineers’ desks.

Within the next six months, the fabricator also plans to implement Epicor’s Advanced Print Management system, which automates much of the document distribution and organization. “This will mean that all the documentation that’s associated with a production release occurs at a press of a button,” Zurborg said.

Tackling Information Waste

Of course, the most complete way to streamline document distribution is to get rid of the physical documents altogether. “After developing our value-stream maps, we found out there was a lot of waste getting information to and from the shop floor, with people walking back and forth between [the shop floor] and the engineering group or purchasing group,” Kuehneman said.

Though it’s not there yet, Skilcraft hopes to go completely paperless, and it has a start. Today many workers on the floor have a tablet. If, say, a technician in front of the welding robot wants to see a 3-D model of a weldment, he can pull it up on the tablet, zoom in and out, and rotate the image. If he has a question about something, he can e-mail or send a message to the front office for feedback. Team members still need to talk, of course, but now interactions are more meaningful and less mundane. There’s no need for an operator to walk to the front office just to clarify simple documentation errors.

They also noticed that many workers spent a lot of the day walking to clocking terminals. Sure, clocking in on a job means the ERP can track job cycle times, allowing it to compare actual times versus the time standards used in quoting, but according to Kuehneman, “We had one person who was walking more than 100 feet to clock in and out of jobs. We cycle through a lot of jobs during the day, and it added up. So we moved the terminals closer.”

On top of this, the company installed nine overhead monitors on the floor (see Figure 3). Driven by the ERP, the monitors display information about jobs being worked on in the area. “At a glance we can tell what job is being worked on and by whom, how they’re doing against the standard,” Kuehneman said. “It also shows how many indirect hours [not associated with a specific job] there are in a group, how many good parts they produced, and how many defects there are.”

According to sources, workers welcomed the real-time feedback. It helped everyone pull together and reach their performance goals. “We have a performance-based scorecard program, and what’s unique about it is that we co-mingle the metrics across different areas,” Kuehneman said. “Productivity goals are tied to quality and on-time delivery.”

An individual process may be incredibly productive and produce no bad parts whatsoever, but the ultimate customer really doesn’t care about that if parts are delivered late. As Kuehneman put it, “Everybody is pulling on the rope toward the same goal.”

Flexible Assembly

Skilcraft has implemented many elements of classic lean manufacturing—including 5S and parts supermarkets—and adapted them for the high-product-mix environment. But perhaps no area required as much adaptation as assembly. One week an assembly team may be putting together lead-lined cabinetry for an airport X-ray baggage scanner, a job with a plethora of electrical connections, with the added complexity of working with thick pieces of lead. Another week they may be putting together less complicated cabinetry.

To account for the variability, the shop has designed its assembly operations with portability in mind. Tool carts and workstations are on wheels. Assemblers use battery-powered tools whenever possible. If tools require air or electrical connections, wires or hoses are hung from overhead reels. This allows workers to adjust the operational layout as needed (see Figure 4).

Identifying Competitive Advantage

No matter how good any contract fabricator becomes, it can’t keep all its jobs all the time. Late last year one of Skilcraft’s major customers pulled its work, not because of any quality or delivery problems, but simply because it wanted to source its manufacturing closer to Asia, its highest-growth market.

Still, that strategy doesn’t always work if fabricators in the local market can’t provide the same level of service. Zurborg described one customer that moved its work to Mexico early last year, but in January, Skilcraft won the contract back. It not only scrutinized how it processes the parts, but it also worked with the customer to provide them low build quantities, delivering a little at a time frequently, instead of all at once. That’s a service the Mexican manufacturer just couldn’t offer.

Zurborg put it this way: “We pride ourselves on working with customers, understanding their demand, communicating it with the production team, and then delivering it to customers on a reliable delivery schedule.”

That’s a concise sales pitch. With all the puzzle pieces for improvement on the table, forever being tweaked and perfected, it’s an honest one too.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI