Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

A “digital thread” runs through FABTECH, North America’s largest metal fabrication show

The 2015 show, the largest on record, emphasizes connectivity

- By Tim Heston

- January 6, 2016

- Article

- Shop Management

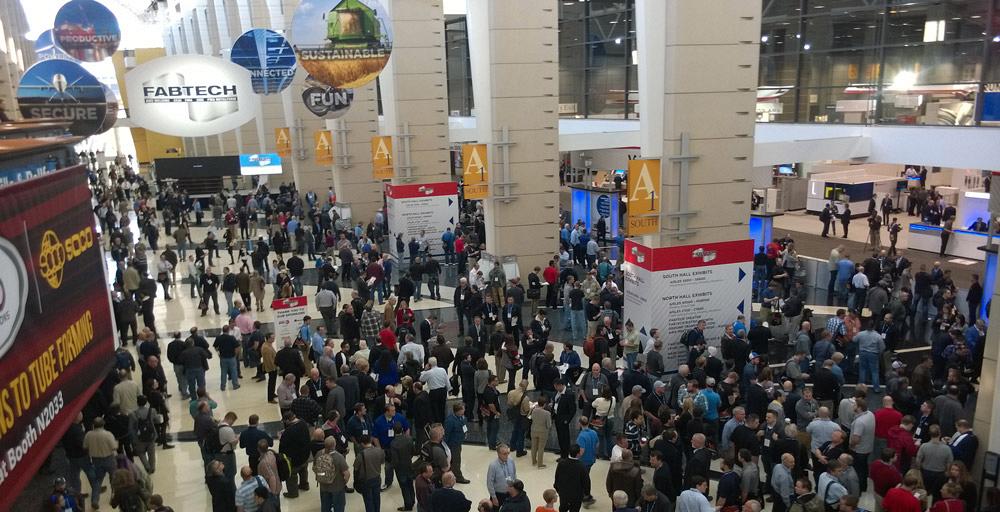

Figure 1

FABTECH broke attendance records again in 2015. More than 43,000 people attended the show in Chicago in November.

John Axelberg came to FABTECH® 2015 with a tall order. The president of General Sheet Metal Works in South Bend, Ind., has a new plant to fill. Opening later this year, the factory will have a front office surrounded on three sides by the shop floor, with a wall of windows in between. When people start their first shift at the new facility, everyone will walk in the same door.

“We recognized that we needed to create opportunities for people to communicate,” Axelberg said. “So one of the easiest ways to do that is to bring everybody in the company through the same front door. There is no separate office door and another door for shop floor employees. Having one door creates opportunities for conversations.”

FABTECH has always spurred plenty of opportunities for conversation and good communication. For the show that took place Nov. 9-12, which drew a record-breaking 43,000 attendees to McCormick Place in Chicago (see Figures 1 and 2), communication was an overarching theme, both in the human and technological sense.

Accessing and communicating the right information at the right time has become central to the metal fabrication business, just as important as efficient material handling automation, fast weld deposition rates, more strokes per minute on the press brake and punch presses, or fast cutting and rapid traverses on lasers.

To get the right information, people and machines need to be connected somehow. Connectivity is a buzzword that until recently didn’t seem anchored in reality. Most shops still worked with some paper drawings, manually entered work orders, and entered programs standing by the machine control. To be sure, many shops still do all of this, but the tradeshow may be a harbinger for a more connected future.

Building a Digital Thread

Driving this point home was keynote speaker Karen Kerr, director of advanced manufacturing at GE Ventures. “We now connect the machines in our factories,” she said. “We need to build an industrial cloud, collect data from machines, and perform a deep analysis. And we’re creating a digital thread to communicate with customers and supply chain partners.”

Why, she asked, do manufacturers in the supply chain e-mail CAD drawings and other files to each other? Why couldn’t everyone access files on one platform? This would allow everyone, as Kerr put it, “to work from one single version of the truth.”

Getting to that truth also requires the right perception and company culture, as described by several speakers at the FABTECH conference.

“You don’t want innovation to serve the process. You want innovation to serve the company.”

So said conference presenter Cullen Hackler, executive vice president of the Porcelain Enamel Institute. His point applied to a broad range of practices in really any type of company, but the comment certainly rings true in metal fabrication.

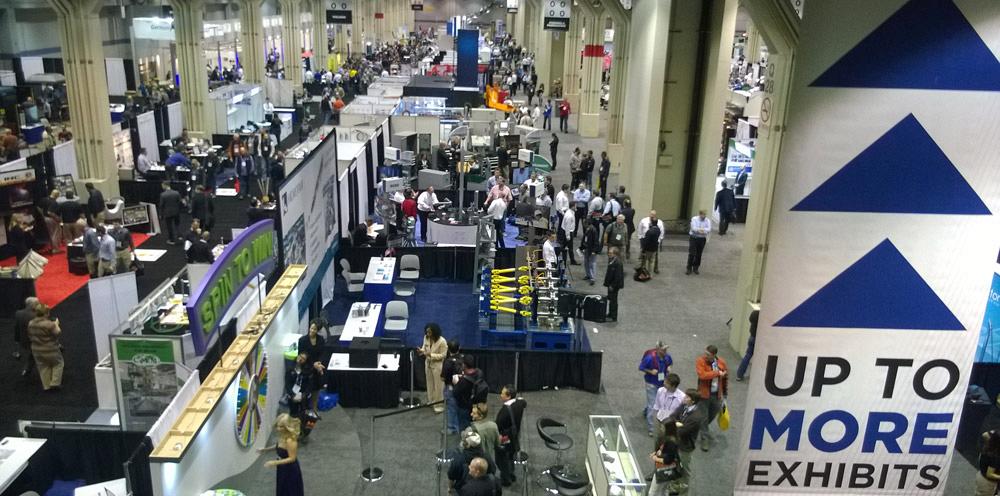

Figure 2

The 2015 show was the largest FABTECH both in terms of attendance and exhibit space. More than 1,700 exhibitors filled more than 760,000 square feet, taking up three complete halls at McCormick Place.

Exhibitors touted machine processing speeds, but many also emphasized the need to look at the entire manufacturing cycle, from order entry and engineering to final shipment. If a technology or business process innovation doesn’t improve the operation—that is, reduce costs, improve profits, or make customers or employees happier—then that innovation doesn’t really serve the company.

Cutting Trends

Attendee Dee Roskelley, vice president of procurement at Richards Sheet Metal, said that his Ogden, Utah-based shop hasn’t yet invested in fiber laser technology. “Our biggest need for equipment is that we don’t have a fiber laser, and we recognize that we’re losing a competitive edge because of that.”

Fiber lasers dominated the show, and machine-makers continued to tout the solid-state laser’s ability to cut a variety of metal thicknesses. MC Machinery Systems (www.mcmachinery.com), for one, offered a new Mitsubishi fiber laser. It has a zoom cutting head with an autofocus that allows multiple sheet thicknesses up to 1-in.-thick mild steel to be cut.

Another type of solid-state cutting laser stepped into the ring at the show. It’s called the direct-diode laser, a kind of laser that for years has been used for various kinds of materials processing. Now the laser has the beam quality to make it applicable for more laser cutting applications.

One machine-maker, Elgin, Ill.-based Mazak Optonics Corp. (www.mazakoptonics.com), had on display a direct-diode tube laser, dubbed the Versatile Compact Laser, or VCL. In welding, Panasonic Factory Solutions (www.panasonicfa.com) demonstrated its robotic welding system also using a direct-diode laser.

High-brightness direct-diode laser developer TeraDiode (www.teradiode.com) uses what it calls “wavelength beam combining.” Basically, the company combines diode bars that emit light of slightly different wavelengths by sending them through a diffraction grating. Once combined in such a way, these different wavelengths produce one powerful, high-quality beam (see Figure 3).

Keeping up With the Laser

No matter how much cutting capacity a shop has, it doesn’t mean much if the processes upstream and downstream can’t keep up, and this again is why having the right information at the right time—central to Kerr’s digital thread—is becoming more important. Companies touted software to shorten and sometimes completely automate order entry, nesting, and programming. Programs are then sent to the cutting system and on to bending, with automated tool changes, eliminating manual tool setups between short runs.

Both Amada (www.amada.com) and LVD Strippit (www.lvdgroup.com) had their automatic tool change press brakes on display. And Salvagnini (www.salvagnini.com) brought its press brake that’s capable of making automatic tool adjustment (what the company calls ATA), which varies the punch length and V-die width in seconds.

Companies like Cincinnati Incorporated (www.e-ci.com) and Bystronic (www.bystronicusa.com) showcased small, low-tonnage electric press brakes that can be moved quickly as needed with a crane or fork truck. According to sources at Bystronic, some fabricators now move these brakes adjacent to different punching or laser cutting centers, quickly level them using a smartphone app (see Figure 4), and have them up and running for the next job within minutes. Because laser cutting has become so automated, one operator can initiate and monitor cutting while also bending certain components on the adjacent press brake.

For a bending operation to be flexible, it also needs a control that’s easy to operate. In the Accurpress booth (www.accurpress.com), Toshi Sakai, president of Orbit Technology Corp. (www.otc.net), showcased his company’s touchscreen technology (see Figure 5).

Figure 3

Toshi Sakai of Orbit Technology Corp. demonstrated a touch-sensitive controller projected onto the front of an Accurpress brake.

“This is like the Xbox Video Kinect,” Sakai said. “I wanted to use a gesture-based system. Now anyone can bend a part, and the instructions are right there in front of you.”

The control mounts on the side of the press brake, and a system on top of the machine projects a large touch-sensitive display onto the entire front of the machine. If an operator needs to check his bending sequence or manipulate a 3-D model of the part to get a better view, he need only look up and touch the display right in front of him.

TRUMPF (www.us.trumpf.com) introduced a software platform, AXOOM, to connect all parts of the metal fabrication process, not just the production activities. Florian Weigmann, CEO, AXOOM, which is being launched as a separate company, said the goal is to automate aspects of metal fabricating that have grown only more complicated with the emergence of more low-volume jobs. Customers and suppliers to the metal fabricator can have their operations networked together so that parties can have insight into operations that might influence production and delivery times.

Just across the aisle at the Amada booth, attendees saw high-mix, low-volume automated production in action. The company called the display its “automated blank to bend” presentation. In it, one fiber laser, connected to a material handling tower, sent parts to two robotic bending systems, with staging bins set up for multiple parts and kit-based part flow. The fiber laser on display was capable of cutting both thin and thick material and featured nozzle change automation and in-process monitoring.

Digital Welding

This and other booth presentations focused not on how fast a certain machine is, but how a technology can fit seamlessly into the entire process chain—a chain that includes welding.

In robotic welding, offline programming and simulation technologies were on display again this year, as well as new methods of programming. Tucked away in the corner of ABB Robotics’ (www.abb.com/robotics) booth was a small robot cell with monitoring attached. It didn’t look particularly special, except for what the operator was doing. The individual kept tracing his finger along a metal joint in a fixtured workpiece underneath the robot welding gun. On the monitor, the path on which the finger followed was highlighted in a bright orange and red hue, similar to an infrared screen capture.

This basic exercise demonstrated a new robot teaching process Microsoft and ABB are developing. A monitor captures the finger movement, and software translates the 3-D image into code for the robotic welding arm to follow. An ABB spokesperson said the prototype was not ready for commercialization, but was proven enough to demonstrate at a show full of fabricators and welders.

Major welding players touted the importance of process monitoring, and part of that includes connected welding power sources that can communicate data—including welding arc-on time and amps and voltage levels—to a fabricator’s server as well as off-site (that is, “cloud-based”) data centers.

Monitoring and improved welding technique go hand-in-hand, and this fact was on display at Realityworks (www.realityworks.com), an Eau Claire, Wis.-based company that currently focuses on the welding education market. The company showed a welding helmet that, using visual sensors, can instruct the welder in real time. Information from welding procedure specifications (WPSs) connects directly with an in-helmet system that gives welders real-time instruction, with visual cues in the helmet itself telling the welder to change the gun angle or travel speed, for instance.

According to Jamey McIntosh, product manager, the system has been sold mainly to schools. However, several companies have expressed interest in adopting the technology in the fab shop.

Information Wins the Race

“Training is a huge obstacle right now, because we’ve grown so much recently. Within the past five to six years, we’ve increased our business about 40 percent.”

So said attendee John Karp, manufacturing engineer at Vista Outdoor. That growth would be impressive for any company in manufacturing, but it’s especially impressive considering Vista’s size. More than 1,600 work at the company’s Anoka, Minn., plant. “We’re attempting to establish well-written instructions and visual controls. And we’ve actually launched a continuous improvement team to address a lot of these issues.”

A company’s growing pains can be overcome in part by technology, which the FABTECH show floor demonstrated with gusto. But the pain also has to be overcome from a business process standpoint. In a conference presentation about sustaining process improvement, Paul Vragel, president of 4aBetterBusiness Inc., described several stages most best-in-class companies go through to sustain improvement efforts. The first is the “just do it” phase. Once people do the task enough, they move on to the second phase, when the process becomes somewhat repeatable.

The next few phases involve process-driven approaches, with staff buy-in, clear documentation, and a common understanding of what that documentation means. Eventually the company institutes systems in which certain information spurs action; in other words, improvement becomes automatic.

He added, however, that many small companies never move beyond the second phase, or as Vragel described it, “the phase in which we’ve done this enough to know we achieve most of what’s expected most of the time.”

This is understandable, in one sense, considering the gumption it takes to launch a business in the first place. Small-business owners like to be flexible, yet at some point the business becomes too large or complex to manage without clearly defined processes and procedures.

Considering all this, it’s no surprise NASCAR® legend Rusty Wallace was a hit keynote speaker at the show (Figure 6). Auto racing has it all. It’s fast-paced and has a history of people going by their gut to make things happen, not unlike the owner of small job shops. Yet all the frenetic activity has a backbone of some solid and often incredibly advanced engineering that must abide by physical and regulatory constraints: this part needs to be of such and such material, and so on. NASCAR has a lot of rules.

Racing teams need to move so quickly that basic processes must be mapped out and documented, ready so that anyone can react on a moment’s notice. That’s not unlike the process development and documentation that occur at a growing custom fab shop.

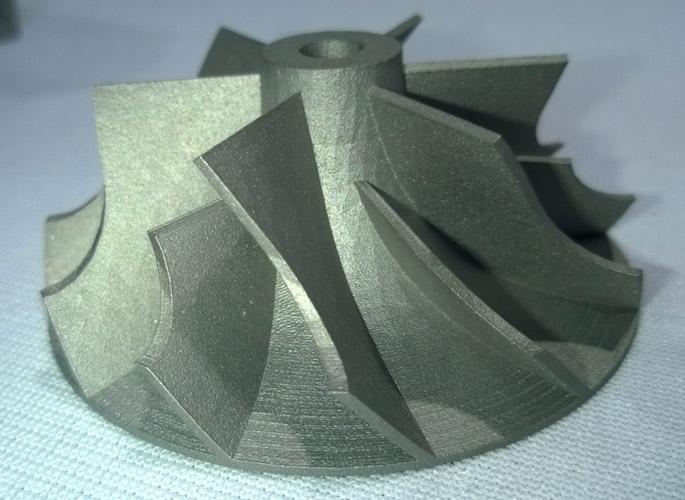

It’s also no surprise that Bob Markley got his start in racing too. Markley owns Indianapolis-based 3rd Dimension (www.print3d4u.com), a firm that specializes in industrial 3-D printing. His company exhibited in FABTECH’s additive manufacturing area near the show entrance, alongside other companies in this new but growing manufacturing arena.

This included Cincinnati Incorporated’s BAAM, or big area additive manufacturing, system, which spent its time at the show printing chairs, tables, and other large objects. Earlier the system also printed a Shelby Cobra racecar and a kayak, both displayed on the convention center’s main concourse (see Figure 7).

Figure 5

The body of this Shelby Cobra, parked outside the Grand Ballroom in McCormick Place, was printed using Cincinnati Incorporated’s BAAM, or big area additive manufacturing, technology.

While the BAAM system prints using a carbon fiber-reinforced polymer, 3rd Dimension specializes in an even narrower niche: industrial metal printing (see Figure 8). While attending Purdue Polytech, Markley worked on racing teams, including an Indy car team. After a stint at Rolls-Royce and GM, he had a hankering to get back to a faster pace of working but, now with a young family, without so much time on the road.

“I heard something about 3-D printing, probably on NPR, and I said, ‘Let’s take a look at it to see if this has any legs,’” Markley said. “It was one of my harebrained ideas that actually worked.”

The pace of innovation in 3-D printing is not unlike the engineering wizardry performed by modern racing teams or, for that matter, the mechanical magic of the machines on display at McCormick Place.Regardless, having the right information at the right time—be it a collaborative design effort on a 3-D printed part or a last-minute schedule change at a custom fabricator—ultimately helps win the race.

FABTECH is sponsored by the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association International (www.fmanet.org), the American Welding Society (www.aws.org), the Precision Metalforming Association (www.pma.org), SME (www.sme.org), and the Chemical Coaters Association International (www.ccaiweb.com). For more information on FABTECH, visit www.fabtechexpo.com.

Economic outlook from those at the show: It’s complicated

For business leaders who attended FABTECH in November, the economy in 2015 and 2016 will surely prove how valuable having the right information at the right time really is.

“We’re experiencing some slowdown in some areas and more business in other areas,” said Cody Cuhel, marketing manager at Winsted, Minn.-based Millerbernd, a heavy fabricator that exhibited at the show. “We’ve made some adjustments this year. And for 2016, we’re expecting business to remain flat or be a little bit up [from 2015].”

You might think this would be a typical report from fabricators, considering the broader economic indices. The Institute for Supply Management’s PMI, which in late 2015 fell below 50, into contraction territory, is just one example.

But the story is a little more complicated. South Bend, Ind.-based General Sheet Metal Works, for instance, has benefited from a significant amount of work from the solar industry for mounting and tracking systems. “2015 was an absolute record, and 2016 will be even bigger,” said John Axelberg, company president. “There’s an investment tax credit that drops from 30 percent to 10 percent at the end of 2016. The future will depend on Congress and the presidential election, but we anticipate a big dropoff in 2017.”

Rockford, Ill.-based Superior Joining Technologies (SJT), a specialty welding and fabrication operation that exhibited at the show, also reported record earnings. “September [2015] was one of our biggest months, and [in 2016] we’re relocating into a building that’s five times bigger than what we have now,” said Teresa Beach-Shelow, one of SJT’s owners. “Keep in mind that our customer mix is 85 percent aerospace, and aerospace is doing very well.”

Figure 6

A small metal part, “printed” by a laser melting process that uses metal powders, was made at 3rd Dimension, an Indianapolis firm that exhibited in the show’s additive manufacturing area, near the main concourse.

As these and other fabricators report, the health and level of business depend greatly on not just what industries the shop serves, but what components and products the shop fabricates for that industry. It really is about being in the right niche.

For instance, Spec Fab is a custom fabricator based in Honey Brook, Pa., just a few towns over from where agriculture equipment-maker New Holland has its roots. You might think Spec Fab would be having a rough year, considering who its major customer is.

“The demand for huge machinery, like harvesters and combines, is way down. But the demand for [the smaller machines like] hay tools, including balers, is up, and that’s what the New Holland plant [in Pennsylvania] makes.”

So said attendee John Reed, Spec Fab’s shop manager, who added that the custom fabricator expects double-digit growth next year, despite the broader state of the agriculture machinery segment.

The subtleties of the economy have confounded industry observers, including economists themselves. “Every single thing that happened [in 2015] took economists by surprise,” said Chris Kuehl. The economic analyst for the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association spoke at the organization’s annual economic forecast breakfast at the show.

China is not the China of just a few years ago. Leaders of the second-largest economy want to make the country’s currency, the RMB (yuan renminbi), a currency of global trade. Earlier this year China let the RMB fall in value, which sent jitters through global markets. “But China was just reacting to the [International Monetary Fund] saying it needs to let the currency float,” Kuehl said. “Will China keep its currency lower? In the past, the answer would be yes. But not now.”

On top of this, Kuehl added that “we’re entering a whole new era of oil.” Unlike the 1970s when OPEC reigned supreme, no one entity has dominant control over the price of oil, and the U.S. has become a major oil and gas producer. The Middle East and Russia (the latter of which needs to sell its oil and gas at any price) keep pumping. Sure, the Keystone Pipeline was scuttled, but the argument over that pipeline was overshadowed by the fact that the supply of fuel now seems to be outweighing demand.

“Years ago we talked about peak oil,” Kuehl said. “Now we’re talking about peak demand.” Energy consumption is down in the U.S., Asia, and especially Europe, and “industry is also using less energy.”

The push toward using less fuel seems to be a long-term trend. Regardless of the short-term price of fuel, using less of it may just make business sense.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Hypertherm Associates implements Rapyuta Robotics AMRs in warehouse

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI