Contributing Writer

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Fabricators and their power hammers

Here’s an overview of the brawny tool by the people who use it

- By Jeffrey Dean

- June 2, 2016

- Article

- Shop Management

Figure 1

Power hammers are among the oldest metal fabricating tools known to man. They just happen to be smaller today than they were several hundred years ago.

There’s no mystery to the allure of a power hammer. It’s loud and powerful, while also emitting a whiff of implied danger.

Then there’s the power hammer’s practical side. It does the work of two stout men with 5-lb. sledges or 5-oz. planishing hammers. (Yes, they can be that delicate.) They hit hard and accurately. You can use one for a forge weld, or even as a quick-release vise for twists.

The idea of a power hammer goes back to antiquity. Records indicate that the Chinese employed them as early as 200 B.C. Power hammers were part of Europe’s industrial landscape as early as the 12th century. Of course, those were more correctly called trip hammers, and they worked like hefty blunt guillotines. A series of mechanical pulleys, gears, and cams hoisted the heavy hammer aloft, from where it was released. Gravity did the rest. Some of these hammers were immensely heavy. Typically, steam- or water-powered wheels provided the horsepower to raise the hammer back to its high position.

The flaw in this system was that the power of these early power hammers was directly related to their weight. In theory, at least, there was no limit to how heavy a hammer could be. The other part of the equation was that you still needed a way to lift it. So most trip hammers, except for a few wonder-of-the-world oddities, were kept to reasonable weights that wouldn’t exceed the capacity of the average steam engine, water wheel, or yoke of oxen or peasants.

The advent of the true power hammer solved the weight-lifting problem. It was an innovation that multiplied the hammer’s oomph by accelerating its downward motion. This meant that a power hammer could deliver the power of a trip hammer at a fraction of the size and weight. While no one man is credited with its invention, the power hammer began to find increased use across industrialized Europe around the end of the 18th century. By the mid-1800s, the power hammer totally eclipsed the trip hammer.

The earliest specimens were big boys, to be sure, used mainly for forging massive parts for locomotives and ships. However, the downsizing trend continued, and the first part of the 20th century saw power hammers (see Figure 1) that were small enough to fit into the average smithy or fabrication shop. Some were steam-powered, but electrical motors drove the majority of them.

Today’s power hammers fall into one of three categories: mechanical, utility, and self-contained. This might be a good time to mention that all power hammers are designated by relative hammer weight. That is, their relative size describes the weight of the actual striking surface plus everything behind it, including the ram, piston, levers, and gears that power and guide the hammer. The truth is, though, this is a frivolously arbitrary system. No two manufacturers make their hammers with the same hammer actuating system. So only two hammers with a shared factory birth could actually be compared to each other in terms of hammer weight. Still, the nomenclature works on a rough level for comparisons.

Mechanical Hammers: The Little Machines That Could

Mechanical power hammers are powered by an electric motor. They typically run smaller, with a narrower throat. This limits the type of work they can do because the smaller opening precludes the use of tools and dies. But for drawing metal down, they are demons.

These are the machines that first appeared in blacksmith shops at the dawn of the 20th century. If you see one today, chances are it’s a Little Giant. Some of the first ones ever built remain in service.

“Mechanical hammers were designed mainly to resharpen and re-edge agriculture tools,” said Ralph Sproul of Bear Hill Blacksmith in New Hampshire.

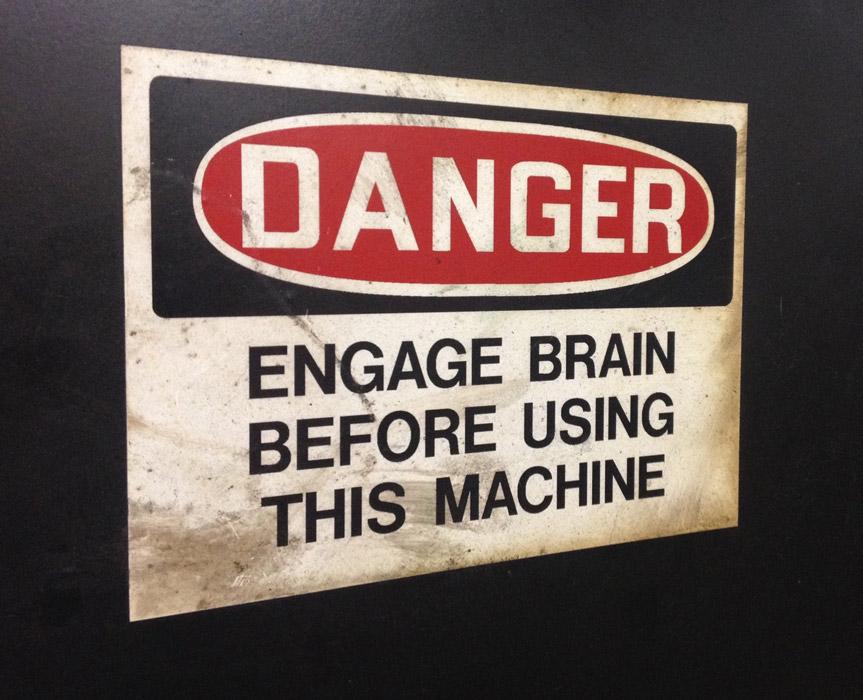

Figure 2

This original manufacturer’s warning plate on this power hammer reminds the operator of the power of the tool being used. Photo courtesy of Artisan Iron.

Indeed, that is precisely what Trenton Tye uses his 100-lb. Mayer hammer for. Tye, who owns Purgatory Ironworks in Morgan, Ga., is a well-known reforger of peanut blades. A peanut blade is the ground-level component of an agricultural implement for harvesting the nation’s multimillion-dollar crop of goobers.

Mayer hammers share DNA with the Little Giant, both having been developed by the eponymous Mayer brothers of Mankato, Minn.

Dave Court, who runs Bay Hill Forge in New Hampshire, has a 50-lb. Little Giant among his collection of power hammers.

“It was cast in 1910,” Court said. “I have its pedigree. It was shipped to Littleton, N.H., in 1911. I’ll put it against any hammer in America.”

While limited in throat space, Court’s Little Giant does have room for stroke adjustment.

“With the flywheel on it, you can get a single precise blow or [repetitive blows] like a machine gun. And it’s very accurate,” he said. A cone clutch, a hallmark of the Little Giant, makes the machine self-aligning.

The Little Giant was more than enough for the production work Court was turning out back when he was doing only hardware. But he readily conceded that his larger power hammers have capabilities that the mechanical hammers can’t touch.

“You can always do little work with a big hammer, but you can’t do big work with a little hammer,” he said.

Utility Power Hammers: Bring Your Own Air

Think of utility hammers as the stripped-down versions of air hammers. You supply your own compressor.

Elmer Roush of California runs three hammers, two of which are utility types, a Trip Air and a Big Blu. He powers them with three 5-HP, two-stage compressors. The three motors feed a manifold with a single pipe to feed the hammer in use. (Maybe it’s a California thing: most fabricators simply use one compressor.) It generally takes between 20 and 25 cubic feet per minute (CFM) to drive a power hammer of 120 lbs., for which a 5- or 8-HP compressor works nicely.

Figure 3

The utility hammer at the Ball & Chain Forge has enough daylight to accommodate an 8-inch swedge. Photo courtesy of the Ball & Chain Forge, Portland, Maine.

Ray Ciemny of Artisan Iron, Groton, Mass., uses a 10-HP Speedaire machine to run his 125-lb. Bull hammer (see Figure 2).

“You need big CFMs. That’s the key with these things. And you run all the valves and pipes open wide. You can’t choke anything down,” he said.

Ciemny bought the hammer when his 30-lb. Bradley mechanical hammer was limiting him for the production work he was getting into.

“I found the Bull hammer in North Carolina. It came with a factory plate that said, ‘Engage brain before operating this machine.’ The hammer was [made by] a quirky husband and wife inventor couple,” Ciemny said. That couple, Tom Troszak and Denise Mills, today makes a power hammer under the name Phoenix Hammers.

Ciemny bought his hammer more than 10 years ago.

“The throat is about 11 inches,” said Ciemny, “so you can use it with normal blacksmithing top tools.”

The ample throat is not the only thing Ciemny likes about the Bull hammer. The dies are held by just two bolts, making them fast and easy to change. And it’s a relatively compact machine, weighing just 650 lbs.

Bob Menard, who runs the Ball & Chain Forge in Portland, Maine, also avails himself of the Bull hammer’s compactness.

“I don’t have clearance for a big hammer, and [for its size] this one hits like a ton of bricks,” he said.

As is typical of most air hammers, Menard’s hammer (see Figure 3) has a wide open throat.

“It’s got 14 in. of daylight. I can fit 12- by 8-in. swage block on its 8-in. side in there,” he added. Menard runs the power hammer with a 7.5-HP compressor with an 80-gal. tank. It puts out about 18 CFM, according to Menard, who spends most of his time working on railings and gates.

Self-contained Power Hammers: Big Iron for Serious Ironwork

Those that don’t want to bother with acquiring a dedicated compressor have another option: self-contained power hammers.

A step up from the utility hammer, the self-contained hammer has its own built-in air compressor and tank. Like the utility hammers, these hammers have a lot of daylight between the workpiece and the business end of the ram. You can fit all manner of hand tools and dies in the typically 12- to 14-in. throat.

Self-contained hammers are hefty boys. They are usually in the upper size range of power hammers found in a fabrication shop. Of course, not all shops have hammers the size of Ralph Sproul’s.

Sproul, so the story goes, got a call from a friend in Minnesota, who had heard about an old Nazel in Everett, Mass., and wanted Sproul to take a look at it for him. But when Sproul locked eyes on the machine, he was smitten. The power hammer, which had been built in 1906 and done three-shift duty during two wars, was sitting in a maintenance shop in a state of advanced decrepitude.

When Sproul asked shop personnel to fire up the pile of junk and asked them for a piece of scrap steel, the guys cracked wise. But when he used that 12,000-lb. tool to transmogrify the steel into a delicate leaf pattern complete with stem, the shop personnel sobered right up. Sproul offered his friend $4,000 and promptly had the leviathan shipped to his shop in New Hampshire.

Sproul is not the only fan of self-contained hammers. While Tye does use a mechanical hammer for a lot of his work, his go-to hammer is a 110-lb. Sahinler self-contained hammer. Roush considers his 100-lb. Sahinler his primary hammer.

Bigger Is Smoother

Aside from the convenience of a built-in compressor, the greater mass of the self-contained hammer is an advantage. In short, the mass of the machine absorbs vibration. Less vibration means less maintenance. It also means more comfort for an operator by dampening the unpleasant sensation that’s transferred through the workpiece to the forearm.

You could liken the vibration to the recoils that a light and a heavy firearm generate. Court called it “white knuckle disease,” technically referred to as hand-arm vibration syndrome (HAVS). Research both here and in the U.K. has implicated power hammers as a suspect in the syndrome. In any case, heavier hammers that generate less vibration are certainly more comfortable for the operator. For example, after souring on a modern 205-lb. hammer with a total weight of only 6,000 lbs., the maintenance shop from which Sproul purchased his more than 100-year-old power hammer asked if it could buy the now fully operational 6-ton Nazel back from Sproul.

(Here’s a technical note about vibration: If you’re experiencing shock in your forearm and hand from a jumpy piece, you probably are not laying it on the die correctly. If it’s aligned perfectly in plane with the die, the workpiece shouldn’t be hopping around. Sometimes, switching to a radiused die will help.)

There’s no question that any power hammer saves wear and tear on a fabricator’s body. Court bought his first power hammer for precisely that reason. He was developing tendonitis in his forearm.

Finding the Right Hammer

So what should a fabricator look for in a first power hammer? For sheer simplicity and ease of use, a mechanical hammer is hard to beat. Its user-friendly operation makes it a snap for a beginner to gain skill and confidence.

“You can put a beginner on it,” Court said. “It’s easy to adjust and very forgiving.”

A utility hammer might cost twice as much as a mechanical hammer, but it also enables a fabricator to use hand tools and dies, opening up a world of fabricating possibilities. Of course, a shop needs to set up a compressor and that adds to the cost. Tools and dies come at an additional cost as well.

Self-contained hammers eliminate the need for a compressor, but a fabricator should be prepared to write a five-figure check for one. Again, the shop needs to make an additional investment for the smorgasbord of tools and dies to go with the self-contained hammer.

Self-contained hammers are definitely not for beginners. They are typically more daunting to operate. They also require a significant amount of floor space.

Tye offered this advice for fabricators looking for a power hammer: “There’s no secret sauce. Your tool should fit your work, not the other way around. A power hammer is a leap forward—a commitment.”

Artisan Iron, www.artisaniron.com

Ball & Chain Forge, www.ballandchainforge.com

Bay Hill Forge, 603-286-3097

Bear Hill Blacksmith, www.bearhillblacksmith.com

Elmer Roush Blacksmith, www.elmerroush.com

Purgatory Ironworks, www.purgatoryironworks.com

About the Author

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI