Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

From kaizen to kata

One fabricating operation launches a lean manufacturing initiative and finds early success

- By Dan Davis and Stan Whitaker

- January 27, 2016

- Article

- Shop Management

Figure 1

Before kaizen teams tackled the fabrication area, material and laser-cut blanks were moved by lift truck (left). Now a system of carts are used (right), which has reduced the number of lift trucks for the work site to four. Also, operators don’t need a material handler to move a pallet from the laser cutting machine to the press brakes, for example. They just grab the cart and move it to where it is needed.

Every manufacturer has had to adapt to the always competitive environment. If they were trying to take the business-as-usual route, they were usually on the road to going out of business.

It was only a handful of years ago that Camfil APC, Jonesboro, Ark., needed six to eight weeks to deliver one of its dust collecting units. Now, thanks to a modular design that allows for production of more repetitious parts while simultaneously allowing for seemingly endless model differentiations, lead times for the equipment have been cut down to two weeks. But the work didn’t end there.

The company began its lean journey about two years ago in an effort to create a culture where everyone was involved in eliminating waste and implementing more efficient processes. The road to establishing a robust lean manufacturing environment has had a couple of speed bumps, but the efforts have produced a much smoother road for near- and long-term improvements. This article recaps how the company has gotten to that point.

Getting Started

There are numerous ways for a company to get started with lean manufacturing. Fortunately, Camfil APC is an employee-oriented company, and it wanted to get everyone involved.

The first decision was hiring someone to be a lean manufacturing champion. This dedicated expert created the plan and guided the early steps that exposed everyone to lean principles. It was a mass educational undertaking.

The company had done some continuous improvement training in the past. Consultants were used for spot training for specific targets or to cover certain tools, but there was no follow-up after the training. A consultant was brought in to train on quick-changeover processes, for example, but that training was not sustained. Some of those who were trained later left the company.

Before the approximately 170 employees were invited to classes, however, some thought was given to who would make up each class. Not all classes were handpicked, but each one included a mix of personality types and job functions. In fact, the goal in some cases was for classes to reflect value streams in the factory. The rooms were filled with people who relied on each other—directly and indirectly—to complete their tasks in a given day.

The initial educational outreach wound up including 13 one-day training sessions. During each eight-hour class, employees learned that lean manufacturing principles originated in the U.S., were applied to the Japanese economy as it rebuilt after World War II, and are now increasingly being readopted by U.S. companies. They also learned about the eight types of waste and engaged in simulations to help them visualize what that waste may look like in an industrial setting.

This was the first step. It gave everyone a common language to use as the company moved forward in pushing more formal continuous improvement activities.

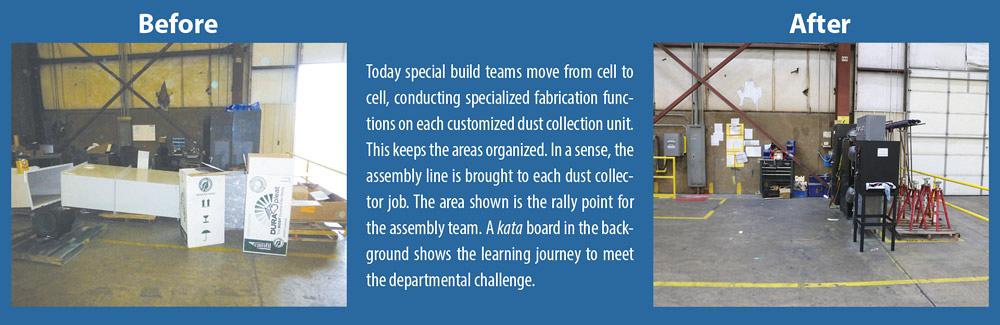

Figure 2

This master scheduling board in the assembly area provides the same visual clues as the welding robot scheduling board. Assemblers used to have a difficult time deciding what to work on because parts could be found all around with no visual reminder for production order (left). Today the scheduling board (right) lets everyone know where every job is located and its status in terms of completion.

Next Step: Kaizen and 6S

With more knowledge and awareness of lean manufacturing, the manufacturing team was ready to tackle some continuous improvement projects—or kaizen events. Kaizen, the Japanese word for improvement (kai means “change,” and zen means “good”), applies to any set of activities in which employees at all levels of a company come together to change a process in an effort to improve productivity.

The focus of these events—in which handpicked strategic teams come together and are focused solely on one improvement project for three to five days—was on what people in the metal fabricating industry would consider low-hanging fruit. These shop floor shortcomings, such as work-in-process lying all over, lack of visual instructions and guidance, and general lack of organization, need to be addressed quickly. Luckily, they can be solved quickly as well. A defined 6S program is the key to sustaining those improvements.

In concert with the introduction of kaizen events, 6S efforts were formally engaged. Fabricators are probably more familiar with the 5S manufacturing philosophy, again based on Japanese continuous improvement practices. 5S covers seiri (sort, or get rid of what is not needed); seiton (straighten, or put everything where it should be and where things are easy to access); seiso (shine, or create a clean workspace free of garbage and dirt); seiketsu (standardize, or set up standards like visual work instructions to maintain a clean work environment); and shitsuke (sustain, or maintain work habits that keep continuous improvement at the forefront of everyone’s thoughts). Some U.S. companies adopted this lean philosophy and later added safety to the mix—the sixth S—because a safe and safety-conscious workforce is made up of individuals that will be present to do the job and engaged to do the job better.

To sustain these efforts, a steering committee comprising top management from different areas of the Jonesboro facility was created. The committee meets and audits once a month, and improvement ideas are discussed.

Each committee member also is responsible for audits, particularly related to 6S. The committee representative is responsible for auditing an area on a monthly basis, and the results are shared on audit boards set up throughout the facility. The auditor is responsible for an area that he or she doesn’t oversee because a fresh set of eyes is more likely to catch something that needs to be addressed than someone who sees the same thing every day and doesn’t think it is unusual.

The kaizen events and 6S activities resulted in visual changes around the facility. One of the major successes involved a reorganization of the laser cutting area in the fabricating department (see Figure 1).

Before reorganization efforts, a slew of pallets sat on the side of the laser cutting machines because each nest might contain six to eight different jobs. The parts for each job were then placed on the appropriate pallet so that when the pallet was delivered to the press brake or some other downstream processing step, all the parts detailed on the routing slip were available for the press brake operator or other shop floor technician.

Not only did the pallets eat up floor space, require forklifts to move them from station to station, present a hazard to employees walking through the department, and pose an ergonomic risk to those who had to put down or lift up parts, they also left the material handler with an unenviable management task: What went to the rack, to the press brake, or straight to welding, and when should the parts get there?

Pallet carts, whereby the pallets are placed on individual carts and pushed to where the job needs to go next, proved to be the key to the lean makeover of the area. It also made life for the material handler much simpler.

Employees no longer have to wait for the lift truck. If the press brake operator needs more work, he can walk over to the laser cutting area and push a cart to his nearby station. If the laser cutting machine operator has a hot job, he can wheel the cart down to the press brake and notify his co-worker of the need for quick processing of the job.

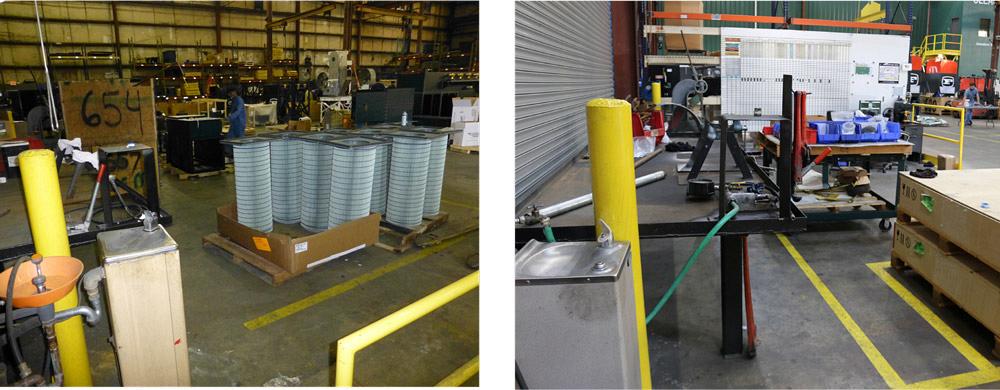

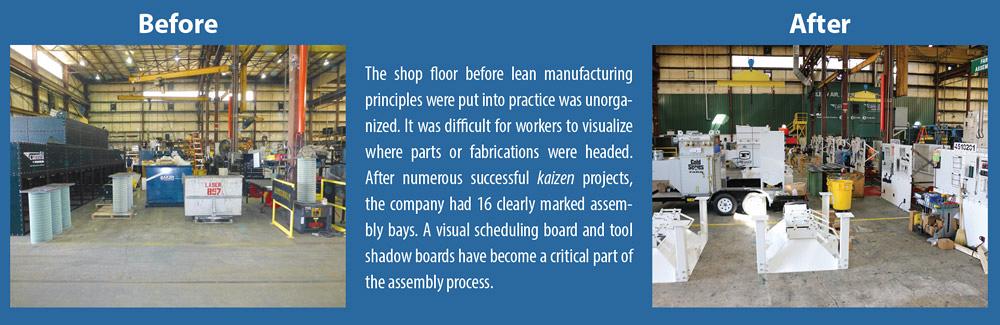

Camfil APC embarked on its lean journey in January 2013, and almost three years into it, the shop floor has changed dramatically. These before and after photos provide a glimpse into that transformation.

The carts also became a visual reminder of just what could be processed at one fabricating station. For instance, no more than two orders are put on a cart. When six carts are in front of the press brake at the beginning of a shift, everyone knows that is about the most that the one press brake operator can finish in a shift. (The average run time of a job at a press brake was used to help determine just how many jobs an operator and press brake can process in a shift.) The laser cutting machine operator then knows not to send any more carts to that press brake and focus instead on work that bypasses the bending area.

Another Step: Kata

With kaizen events up and running and 6S taking hold, some Camfil APC managers attended a conference that explored kata, which is more of a strategic philosophy that addresses an overarching goal but relies on daily steps to work toward meeting that goal.

For Camfil APC, the overarching goal was tied to the company’s vision statement: “Camfil APC’s goal is to be the No. 1 dust, mist, and fume collector manufacturer, producing the highest-quality systems for our customers, while daily improving our employees’ quality of life, our processes, and our products.” A steering group was set up in early 2014 to create other departmental teams that could then start working on more local challenges throughout the manufacturing facility.

That initial effort, however, lost momentum over time. Although management supported the effort, many of the participants underestimated the daily time commitment. Daily meetings became every-other-day meetings, which soon morphed into weekly meetings. Soon people just stopped meeting.

Kata requires a greater level of discipline to execute properly. The team, made up of a “first” coach and a learner from the department and a “second” coach from elsewhere in the facility, have a 15-minute meeting at the same time every day. It is sacred time. No meeting comes before that. No phone calls come before that. That’s why upper management support is so important.

The team has to follow a scripted set of questions. They are prepared to deliver the answers, which gets them closer to a “target condition,” a short-term goal that the team works toward over a one- or two-week period. Every achieved target condition gets them closer to meeting the short-term challenge.

In 2015 the kata effort was relaunched with much better success. Employees see the need to revere the time dedicated to the daily meetings. They realize that they are taking one step forward every single day, as opposed to one or two steps per week.

Some of these teams begin very awkwardly, getting used to this new process and the idea of formal procedures during the meetings, but then they grow in confidence. They ask good questions and provide constructive feedback. In some instances, people work on these challenges at night because they are passionate about solving problems.

A small five-person group representing the core areas of the business steers the efforts, reviews the progress, and creates the challenges that the kata teams work on. This group, which is separate from the larger lean manufacturing steering group, meets once a week on the same day at the same time for kata walks, where they personally visit the different areas of the shop floor to gauge progress.

One of the company’s largest kata successes is in the welding department. The team was charged with the challenge of creating a process or metric board that would define the workload for a robotic welding cell, which was not being utilized to its capacity. In fact, some days the robotic welding cell wasn’t even used.

When it was being used, the robotic cell was used for small parts. It had two sides dedicated to production welding, but really had only about three fixtures, which represented the welding cell’s underutilized state.

The kata team jumped into the project. They tackled the jobs that were already running in the welding cells, performing time trials and keeping detailed notes. Then they started investigating other jobs that might make sense for the welding cells, ultimately identifying at least six parts that are routinely fabricated and rarely have engineering changes.

Needless to say, the move of manual production parts to the welding cells was huge. To see production time improvement of 70 or 80 percent was not unusual. Obviously, producing more parts with the welding robot also resulted in less rework.

To remind the shop floor about production levels in the robotic welding cells, the team developed a schedule board (see Figure 2). Each column, representing a shift, has about 12 hours in it. When a job is scheduled for a welding cell, the operator places a placard in the column that details the part number, quantity, and the time it takes to complete the job. If someone walks by the board, they can see just what parts are going through the welding cell and what is currently being worked on. When the placards reach eight or 10 hours in one of the columns, no one else is allowed to add any more work for that shift.

The Next Steps?

This is just the beginning for the company in terms of formalizing continuous improvement efforts. It’s a good start, and everyone is learning quickly. It just takes a lot of coaching to make these initiatives a permanent part of the company’s culture. Manufacturers have to take it one step at a time and allow employees to learn a different style of thinking.

Those companies that want to boost their own lean manufacturing initiatives should invest in good trainers. They know how to get the people involved and coax positive behaviors out of them.

Additionally, management must support the efforts and be willing to set the example. Any behavioral change in a company needs to be championed by someone with authority, and those people are typically the decision-makers. Leaving such a transformative task to a junior-level employee buried in the engineering or quality department is doomed to failure.

About the Authors

Dan Davis

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8281

Dan Davis is editor-in-chief of The Fabricator, the industry's most widely circulated metal fabricating magazine, and its sister publications, The Tube & Pipe Journal and The Welder. He has been with the publications since April 2002.

Stan Whitaker

Continuous Improvement Facilitator

3505 S. Airport Road

Jonesboro, AR 72401

870-933-8048

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Hypertherm Associates implements Rapyuta Robotics AMRs in warehouse

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI