Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

How managing by valuation is changing Farris Fab

North Carolina fabricator invests for the future

- By Tim Heston

- October 26, 2015

- Article

- Shop Management

Figure 1

Bryan Farris, president of Farris Fab, began selling for

the company when he was 19. He took over the reins as

president in 1991, when he was only 21.

After Bryan Farris interviewed Bogdan Ewendt for the chief financial officer position, Farris walked away from the meeting thinking that Ewendt just wouldn’t be a good fit for his shop, Farris Fab, a 200-employee operation in Cherryville, N.C., west of Charlotte. Farris thought Ewendt seemed a little too strong-willed, a bulldog a bit like himself. Wouldn’t the two butt heads?

“Then something dawned on me,” Farris said, “and I decided I wasn’t going to interview anybody else. I didn’t need someone who’s chicken, who wouldn’t stand up for what he believes. I think sometimes we get too scared to make changes. And I was worried, too, because I had always been a force of one.”

For almost 25 years Farris has seen his shop grow into one of the larger contract fabrication operations in the Southeast. Managers expect sales to reach $24.5 million this year. But during the past year, Farris has turned a new page in his career and a new chapter in the history of his fab shop.

The new chapter was well underway when he hired Ewendt as CFO (see Figure 1 and 2). Ewendt came from outside manufacturing, having worked in mergers and acquisitions. Farris emphasized that he has no plans to sell, but he’s started to manage by valuation—that is, manage the business to maximize its value. “It turns out, if you manage as if you’re trying to sell it, you’re actually managing a damn good business,” Ewendt said.

Technology Mix

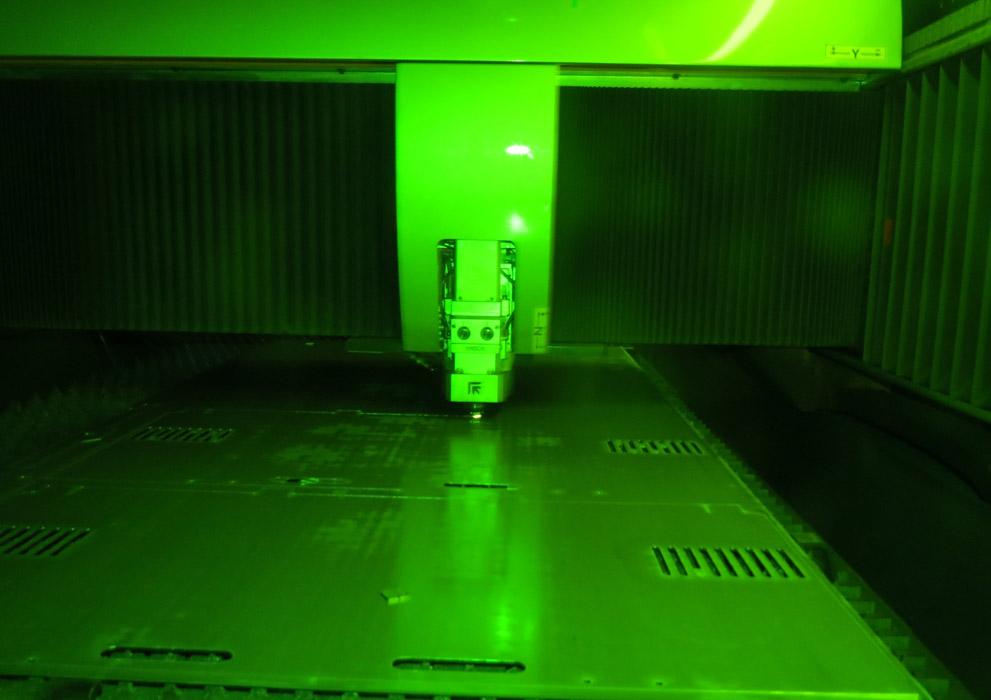

The company has six lasers—one of which is a 5-kW fiber system (see Figure 3)—that flow work to the press brake department, much of which consists of all-electric press brakes with fast bending cycles.

Farris Fab is a high-product-mix operation, so fast changeover matters, which is why Farris and his team devised a color-coded system for press brake tooling in which specific colors represent common punch and die radii (see Figure 4). The company also upgraded to European-style tooling, especially for its newer electric brakes. “We needed better repeatability if we were going to start programming offline,” Farris said.

Parts then flow to manual welding or to one of five robotic welding cells, if a fixture is available (see Figure 5). It’s then on to finishing, powder coating, and final assembly. The shop also has a large machining department that expanded recently when Farris purchased a local small machine shop.

When it comes to machinery acquisitions, Farris has been busy. One negative critique that Ewendt made, in fact, was that the company actually had too little debt. With current interest rates, money is cheap, and no debt at all shows people that the organization just isn’t putting money to good use. So this year the company purchased an automated powder coating line, a new laser, a new press brake, three more robotic welding cells, and a new horizontal machining center.

Information Flow

Farris always has had a knack for walking the floor, sensing the constraint, and fixing the problem. He invested in welding robots to fix the welding constraint and a new automatic powder coat line to fix the painting constraint.

In recent years, though, one challenge couldn’t be overcome with a machinery purchase. Like at many fab shops, Farris Fab now processes more complex assemblies. With this has come more information complexity, especially when it comes to part revisions. Front-office personnel end up walking with stacks of paper to accompany all the job travelers, or routing packets, that hit the floor. One missed revision change can throw a serious wrench into matters.

Figure 2

Bogdan Ewendt, chief financial officer, came onboard last year. He previously worked in mergers and acquisitions.

For this reason the company has invested in a new enterprise resource planning (ERP) package, from ECi Software Solutions, which ideally will streamline the flow of information from the front office to the floor. Ultimately, Farris hopes the shop floor will become nearly paperless. This means that if a revision does occur, the information should flow throughout the organization in an instant. Screens throughout the plant will show workers the schedule, their status in relation to the due date, and the priorities. Farris said ERP integration should be complete within the coming months.

Ewendt added that the lack of smooth information flow may make the business look less attractive from a valuation perspective, and related to this is how deep company leadership goes into the organization. If only one or a few people hold everything together, that’s not a good thing.

Farris is honest when it comes to how he has managed the business over the years. He’s run every machine in the plant. When he sees a problem, he charges out and fixes it. He’s strong-willed and tenacious, and both attributes have helped him build the business into what it is today.

In recent years, though, he stepped back and let others take the helm of managing day-to-day activities. The business became just too large and complex for one person to handle it all, so it seemed like the right thing to do. Unfortunately, the company didn’t have the right processes in place, specifically when it came to information flow between the shop floor and front office, between the office and the customer, and between front-line workers and upper management.

Farris also hadn’t hired a salesperson, and for most customers, he was still the face of Farris Fab. As Ewendt recalled, “When customers had a problem, they would say, ‘I’ll call Bryan.’ They wouldn’t say, ‘I’ll call Farris Fab.’”

So this year the company hired new managers, including a new plant manager and manager of powder coating. Farris also hired—for the first time in his life—a sales manager, who for the past several months has had great success in landing new accounts.

Underpromise and Overdeliver

In recent operational benchmarking surveys compiled by the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association International, many custom fabricators reported on-time delivery rates of less than 90 percent. Farris admitted that there’s one aspect of this delivery problem that has become rampant in recent years, something that may be behind the industry’s on-time delivery performance: Customers are asking for shorter lead times, and fabricators are promising to meet them, even though they really can’t. Sure, a company can improve its operations to process more parts in less time. And some problems are completely avoidable, like when a job is fabricated incorrectly simply because the left hand wasn’t talking to the right. But as Farris explained, some projects just can’t be made any faster, no matter what.

Farris and Ewendt don’t blame the customer, of course. It’s only natural for customers to challenge their suppliers for better service. But when a fabricator agrees and then can’t deliver, that’s a real problem.

Ewendt conceded that for some jobs, “We were promising the world, which meant that people on the floor, including the plant manager, spent time putting out fires. Now, though, the plant manager is starting to see the light. He’s running the plant; the plant isn’t running his life.”

This is coming through both internal improvement efforts (new machines, software, communication practices) and external efforts. People aren’t overpromising. If a customer demands a shorter lead time, the company goes by a policy of honesty.

“Our customers pushed back very little on this,” Farris said. “Customers will always push you, of course, but they also respect you for saying it’s not possible.”

It’s now more important than ever for shops to deliver the right quantity of products at the right time, not too early and not a day late.

As Ewendt explained, when a fabricator overpromises, it actually costs the customer more, because parts aren’t there when they’re expected to be. Today at Farris, people aim to underpromise and overdeliver—or, more accurately, deliver the right product at the right quantity and at the right time.

Early Start

Corwin Farris was still in his 30s when he approached his son Bryan about taking over Farris Fab. At the time Corwin had various side ventures, and he was ready to concentrate on something new. He was (and still is) a serial entrepreneur.

When Bryan was 19, Corwin told him that if he decided to go off to college, he would sell Farris Fab. This was 1988, and at the time Farris Fab was just a small metal shop that had a few plate and sheet metal cutting and bending machines, but mainly focused on machining.

For Bryan, it wasn’t a hard decision; he’d prepare to take the reins of the firm. Even though the shop had been in business since 1979, it grew slowly. By 1988 the company didn’t sell much more than $1 million annually. “So when I was 19, I started adding customers,” Bryan said. “I knew this business wasn’t going to feed both of us.”

Over the next two years he hit the streets, adding big-name customers in the agriculture and construction equipment sectors, and by 1991, at just 21 years old, he took over the family business—one that would grow into one of the largest metal fabricators in the Southeast.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Hypertherm Associates implements Rapyuta Robotics AMRs in warehouse

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI