Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

How one fabricator doubled revenue over 12 months

The story behind its dramatic growth

- By Tim Heston

- October 7, 2013

- Article

- Shop Management

In Gap Partners Inc.’s new facility, parts flow in a large circle. Sheet metal enters from a large loading dock to a small raw stock rack (shown here at the far top left). From there work flows to cutting, deburring, bending, hardware insertion, welding, grinding, and then circles around to powder coating and assembly, where it is staged for shipment.

A year and a half ago Frank Cucchiara was launching a rubber machining and plastic injection molding plant 100 miles west of Shanghai. His employer, TSE Industries, was following the lead of its major customers, including several large ATM manufacturers, to support and sell to Asian markets. So Cucchiara hopped on a plane to Changzhou prefecture to launch Changzhou TSE Rubber and Plastic Products Manufacturing Co.

Now the certified Six Sigma black belt manufacturing executive works at a plant in the mountains of north Georgia, at Gap Partners Inc. (GPI), a fabricator that has seen dramatic growth. Much of it, he said, can be attributed to reshoring, especially for new products. Today companies are launching and manufacturing new products stateside for the same reason Cucchiara’s previous employer opened a factory in China. It turns out that it makes sense to have a supply chain close to the ultimate consumer.

Cucchiara started at GPI in July 2012, after being recruited by Steve Hollis. Years ago Hollis and a business partner, Dr. Sherrie Ford, launched Change Partners, a consulting firm specializing in building of company cultures that can sustain continuous improvement.

More than a decade ago, the two started doing consulting work with an ABB factory outside Athens, Ga. The plant itself was built in 1958 to make Westinghouse’s distribution transformers, those cylindrical sheet metal enclosures atop power poles. ABB purchased the operation in 1990, and in 2003 ABB sold it to Hollis and Ford. The entrepreneurs used this as a platform to launch a new company, calling it Power Partners Inc. (PPI).

In May 2008 PPI purchased a precision metal fabricator in Rabun Gap, Ga., amid the Chattahoochee National Forest, and renamed it GPI. It’s in beautiful, mountainous country, known more for its scenery, bed and breakfasts, cabins, and roadside attractions. On the road from Atlanta, you can take in dramatic scenery at Tallulah Gorge; sample some peaches or apples (depending on the time of year); and visit unusual roadside attractions, like a house with goats munching away on rooftop grass.

It’s not a manufacturing hub, but PPI’s founders saw potential. The fabrication plant is close to a four-lane highway. It’s also nearly at the geographic center of a growing Southeastern manufacturing base.

Most important, they saw precision sheet metal fabrication as a road to diversification and consistent cash flow. PPI’s Athens plant has several successful product lines for the power transmission sector, but it’s a seasonal business. Contract metal fabrication doesn’t have to be seasonal, and it can serve customers across multiple markets.

Moreover, getting into contract fabrication allows the organization to participate in a trend in manufacturing: the push of design services down the supply chain. A purchasing manager on a quest for the lowest per-piece price may work for long-established product lines, but these days, many products have short life cycles. Before you know it, a new design is on the table, and quite often there’s a new or better way to manufacture it. A fabricator’s engineers, who sit steps away from the people and machines that actually perform the work, can help.

When starting at GPI last year, Cucchiara knew this trend all too well, but he also knew that this service could work only if the fabricator could deliver on time quickly. Last year average lead-times at GPI stood at six weeks; today it’s about two. It also has shaved five weeks off average product development time, moving from concept and design to prototype and production in about 11 weeks.

And customers have responded. In 2012 GPI brought in $6 million. This year the fabricator is on track to earn $15 million. Not bad for a year’s work.

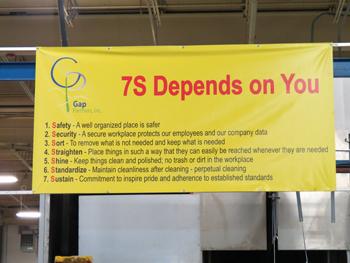

Figure 1: GPI promotes 7S, which adds safety and security to the traditional sort, straighten, shine, standardize, and sustain of 5S.

The Transformation

PPI is the parent organization for Gap Partners, Change Partners—a consulting arm with roots in the founders’ original business—and ECO-MAX™, a company that sells adsorption chillers, manufactured in PPI’s Athens factory. The organization employs 600 and earns about $175 million a year.

The two consultants who launched PPI a decade ago specialized in continuous improvement and culture change—rewarding engaged employees for taking ownership and initiative—and GPI now works by these concepts. But considering the rest of the organization focuses on product-line production, has the parent company’s leadership tried to push a product-line, OEM style of lean manufacturing?

According to Cucchiara, not at all. GPI has goals when it comes to growth and profitability, and PPI’s core values pervade the work culture. For instance, the company promotes 7S, which includes not only sort, straighten, shine, standardize, and sustain, but also safety and security (see Figure 1). The last, which includes the security of intellectual property, has been especially important for companies bringing work back from overseas.

But the GPI plant has a dedicated comptroller, accounting department, estimating, engineering, scheduling, and enterprise resource planning (ERP) system. The organization shares best practices between its plants, but the owners know that the contract fabrication and job shop environment is an utterly different animal. “We have two completely separate business models under one corporate umbrella,” Cucchiara said.

When PPI purchased the fabricator in 2008, the company wasn’t the healthiest. It ran traditional, batch-style production that created significant work-in-process, which is why it took six weeks for most jobs to make it through the shop. Jobs just sat in queue most of the time. Even worse, the company had equipment spread across two buildings—fabrication and welding in one building, powder coating and assembly in another—so parts spent a lot of time being shuttled back and forth.

Since then GPI has undergone a dramatic transformation, and earlier this year it moved into a new facility in the Rabun County Business Park (see Figure 2). The business park consists of 1 million square feet of revitalized factory space, previously owned by Fruit of the Loom Co., and GPI is the first to move in, taking up 92,000 sq. ft. of the original plant.

The floor has one large loading dock, where raw stock is delivered and finished product is shipped. The concrete is thick enough for trucks to pull completely into the building. Quick delivery from service centers near Atlanta allows the company to inventory a limited amount of raw stock. GPI also has a kanban arrangement with its hardware suppliers, which replenish hardware as needed.

Products flow in a circle. The view from the dock facing the factory reveals a small racking area for raw stock to the right, adjacent to a shear. It’s still usually cheaper for GPI to buy standard sheets and, if needed, shear to size. The programmer avoids placing extra parts on the nest. After all, it’s easier to manage remnants of sheared stock than mounds of different-sized cut parts sitting on the floor or in racks.

From there sheet goes to punching, laser cutting, and flat-part deburring. The press brake area is at the top of the circle, next to hardware insertion, welding, and grinding. From here parts disperse depending on the routing. Some are coated with an antirust solution. Some circle around to a semiautomated powder coating line with 600 feet of chain, and final assembly is adjacent to the loading dock. There are no walls. Everyone has a clear line of sight; workers can see the entire operation from pretty much anywhere on the floor.

GPI’s plant floor is clean, everything is clearly labeled, WIP is minimized. Near the front is a large monitor connected directly to the company’s ERP system, giving hourly updates on orders and revenue and comparing those actual numbers to targets. The board also tracks production efficiency. Although not perfect (employees enter data at various points on the shop floor), it gives everyone a rough idea of how effectively parts are flowing. The company holds regular kaizen events to continue its improvement initiatives, and employees have daily huddles every morning to ensure everyone is on the same page.

Figure 2: Earlier this year Gap Partners Inc. moved into its new facility, with an open layout and all processes under one roof.

Employees have a stake in the game thanks to a gain-share program. As performance improves and reduces costs, employees get a share of that savings. They also have a skills-based training system. The more skills they learn—be it press brake operation, laser cutting, or welding—the more they can earn. They then in turn can move to where needed on the shop floor, something that has become critical in the highly variable job shop world.

Managing Growth

A fabricator more than doubling sales over 12 months isn’t a small feat. “This growth is all organic, and it’s all from existing customer lines,” Cucchiara said. “But we offer engineering services in addition to custom sheet metal fabrication, and we’ve been working with several customers on engineering new products. They came to fruition, and it’s been going gangbusters. Their business exploded, and our business exploded.”

Three factors make this growth strategically sound, he said. First, the product lines span various fields, so there’s market diversity: cabinets and enclosures for inventory management systems; LED light fixtures for cell towers and tall buildings; products for live-fire targeting systems; enclosures for fuel management systems; products for freight and passenger rail, power generation, and off-highway equipment; and enclosures for outdoor kiosks.

Second, most of the new work has come from companies that have gotten GPI involved on the ground floor of product design. This strengthens the ties between customer and fabricator. The fabricator isn’t just making parts to print.

Third, product-line manufacturing makes up 50 to 60 percent of revenue. The remaining sales—its job shop business—still come from numerous short-run customers.

“Our strategic goal last year was to become a $20 million [company] in three years,” Cucchiara said. “We’ll hit our targets far sooner than that.”

Communication and Collaboration

The company moved to its new facility over a five-week period, without halting production. Employees worked overtime to build ahead slightly, to accommodate for capacity reductions during the move. And before moving, employees in each department conducted kaizen blitzes to determine how each area of the plant should be set up. Because the new plant was vacant, they were able to visit it several months in advance of the move-in date, with rolls of tape in hand. They taped outlines on the floor where they had decided each machine should go.

That’s why the factory now is set up in one large circle, and it’s also why certain equipment sits directly adjacent to other machines. The flat-part deburring machine is just yards away from the cutting machines. The press brake area is steps away from hardware insertion, and near both areas spans a long welding cell curtain, on the other side of which are 10 stations for gas metal arc and gas tungsten arc welding stainless and carbon steel enclosures. Working near them are the grinders who communicate continually with welders about how best to process the components (see Figure 3).

This arrangement fosters communication and collaboration so critical for high-product-mix situations. If a bent part has a hardware problem, the hardware-insertion technician can walk a few feet to the hardware technician and talk about it. The same goes for the grinders working with welders, or really anyone else in the plant.

Similar thinking went into the front-office design—all open, no walls, and no departmental arrangements. Instead are what could be called front-office cells, with customer service, quoting, and engineering all sitting at adjacent desks. The purchasing managers sit just a few feet away. Everyone gets together during product development, and they hold regular advanced product quality planning (APQP) sessions to make sure everyone knows what’s coming down the road.

Figure 3: To foster communication and ease part flow, press brake technicians, hardware insertion operators, welders, and grinders all work in close proximity to each other.

A Hybrid Plant

The layout works for GPI’s product mix, basically a hybrid consisting of both product-line manufacturing and job shop work. And as product lines grow in volume, employees get together to discuss best practices and potential cells within a department.

For instance, its inventory management cabinet orders have increased to the point where employees are producing about 100 a week (see Figure 4). To streamline flow, employees developed assembly cells dedicated to the line. Two horseshoe-shaped cells accept sheet metal parts emerging from the paint line. One station has operators assembling bases and sides, which are standard components. Then, at later stations, assemblers fill the cabinets with configurable components.

As volumes in the product-line business increase and orders become more consistent and predictable, so does the potential for improvement techniques originally developed for product-line manufacturing. This applies especially to its inventory management cabinets and other higher-volume products. For these, workers hope to change the current routing into something that resembles a pull-type flow with kanban replenishments. And in recent weeks, managers from the PPI plant in Athens, experienced in such lean techniques, have visited GPI to help with setting up such a system.

Instead of the front office releasing work orders to the floor, assembly employees would trigger those order releases as they ship products. Finishing a cabinet in assembly would trigger blanks to be nested in the laser and punch press, and then flow to product line-specific cells.

“We hope to put press brake operation, TIG welding, and hardware insertion all in one cell,” Cucchiara said. From here kits with all the parts for one cabinet will flow to the powder coat line and, finally, to assembly.

Contagious Improvement

Cucchiara said that he expects demand to continue unabated, and if it does, he hopes to invest in some type of cutting automation. The company already has space cleared for another laser. And in another area is space for a higher-tonnage press brake. Most of its brakes have a capacity of 130 tons, but GPI has plans for a 350-ton press brake for bending plate and high-strength material—and there’s big potential here for GPI in the heavy transportation sectors.

The company carefully manages its manufacturing capacity. It does plan to invest in automation, but it doesn’t want to stray toward the chronic overproduction that comes with batch-style flow. “That can fly in the face of lean manufacturing,” Cucchiara said.

Of course, sometimes a fabricator produces and ships large batches all at once because that’s what the customer demands. The company may want a large inventory buffer because it got burned by a supplier that failed to deliver. Or, quite often, a customer’s own batch processing requires a fabricator to ship large batches of parts at once.

That’s why lean manufacturing concepts and other improvement methods enter the conversation early with customers and prospects—usually during the initial sales meetings, which can involve plant tours at GPI and at the prospect’s facility. What are the true needs and pace of manufacturing? How and when should parts be delivered, and what quantity is needed to meet demand? Would, for instance, a kanban replenishment system work (as it does for several of GPI’s largest customers)? Improvement works best when it’s contagious.

At this writing, development work on the new pull-type flow for certain product families continues. For instance, workers are designing material handling carts that can handle certain product families, allowing for one-piece part flow. Everyone knows what needs to happen, but the devil’s in the details. How, for instance, do you time everything so that every component needed for final cabinet assembly—from internal processes and outside suppliers—arrives at the right time? Because of all the disparate products on the floor, perfect line balancing just isn’t in the cards.

Figure 4: GPI General Manager Frank Cucchiara points out an inventory control cabinet, one of the fabricator’s major product lines.

But that doesn’t mean there isn’t room for improvement. In the coming year, employees plan to develop a cell of disparate machines dedicated to producing prototypes, one-offs, small rush orders, and very small runs, all operated by highly skilled, cross-trained employees. This would separate certain small jobs from the principal product-line part flow.

A Manufacturing Sweet Spot

Gap Partners’ story reveals several trends. First, it shows just how valued the contract manufacturing and job shop business model can be, not only for a local economy—GPI now employs 105, 40 percent more than just six months ago—but also for businesses like PPI. Job shop owners often seek to develop their own product line to develop a consistent revenue stream. Now manufacturers like PPI, which have dealt with product line-specific demand cycles for years, look to contract manufacturing to broaden their customer base.

Any metal fabricated product starts with an idea, the design; the job shop or contract fabricator then feeds components to the product-line manufacturer or OEM. So, ultimately, this business boils down to three principal functions: engineering, job shop fabrication, and production. Like other progressive fabricators, GPI has evolved to include all three.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI