Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Managing the three legs of the custom metal fabrication stool

It’s about people, processes, and technology

- By Tim Heston

- January 27, 2017

- Article

- Shop Management

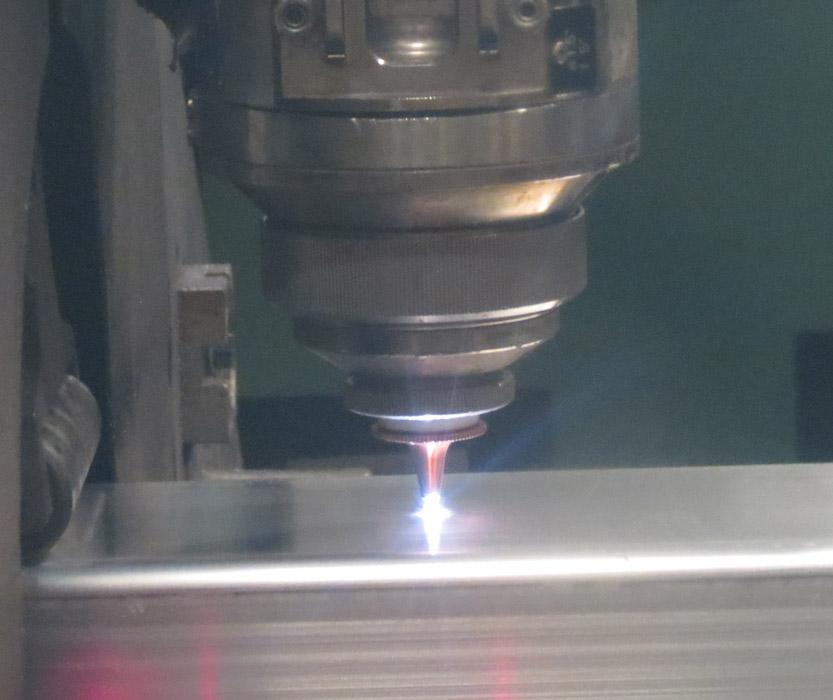

In many ways, laser tube cutting exemplifies competitive differentiation in custom metal fabrication, though part and process design drives the technology’s success.

In 2013 the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association International® hosted a lean manufacturing event that involved tours at several shops in the Midwest. At one of those shops, the late Dick Kallage, a lean consultant and former columnist for this magazine, stood in front of a newly acquired tube laser. He turned around and asked a question: “What’s stopping a competitor down the street from purchasing the very same machine?”

Attendees came up with plenty of answers, but all of them were circumstantial. Competitors may not have the financial resources, or perhaps the owners have a different business strategy. Still, all agreed, the equipment isn’t custom-built or proprietary. Legally, there was nothing stopping every competing custom fabricator in the area from buying the very same machine. In fact, this is a pretty close-knit industry. Word gets around. Shop owners know they can’t keep a new machine secret for long.

Still, how this Midwest shop—and any successful fabricator, for that matter—uses the tube laser exemplifies the true competitive nature of custom metal fabrication. It’s not just about the machine.

Consider one sales and marketing roundtable discussion during the 2016 FABRICATOR’s Leadership Summit, part of the FMA Annual Meeting. One shop manager was transforming his company from a product-line to a contract manufacturer. Another was looking to expand his customer portfolio. And another manager had just bought a laser tube cutter. The manager whose employer had just bought the machine seemed to be the odd one out. A tube laser relates to technology, not sales and marketing—right?

The company happened to have one of the largest (if not the largest) laser tube cutting machines west of the Mississippi. (For more on this, see “A big leap into big tube cutting” from the June 2016 issue, archived at www.thefabricator.com.)

But he also knew that to sell what this technology could produce required a technically competent person with good ideas.

Although this is changing as the laser tube cutting market matures, traditionally engineers haven’t designed parts with laser tube cutting in mind. It’s the ideas from fabricators that have helped laser tube cutting mature. Those ideas have helped ease assembly, reduce piece-part weight, and improve quality.

Good equipment has become the “ticket of entry” to compete in metal fabrication, but most shop owners know that equipment alone can’t make a fabricator successful. If you give the best people in the world an old, poorly maintained laser, plasma cutter, press brake, or welding system, you’ll have a shop full of talented, frustrated employees and, ultimately, frustrated customers. If you have the best machines in the world but don’t have talented people who can operate them and (just as important) communicate and sell the services those machines make possible, you still get frustrated employees and customers.

It really boils down to three legs of a stool: people, processes, and technology. And you need all three. What good is a great design idea or an eye-popping laser tube cutting system if a shop can’t deliver parts reliably ontime because of faulty processes? And the “process leg” is a key differentiator.

“Is there a reason this couldn’t work?”

Kallage asked this question in 2013 during the same lean manufacturing conference, pointing to a PowerPoint slide detailing a potential shop layout. Instead of a typical departmental arrangement (cutting department, bending department, welding department), the layout resembled a grid like a checkerboard. On one row of squares were laser cutting and punching machines; on the next row were press brakes; in the next row was welding. Between the rows were secondary processes such as deburring and hardware insertion.

The grid maintained process-specific departments in rows but introduced smooth part flow with columns, with bending only steps away from cutting, welding only steps away from bending. The layout would require some walls, separators, and ventilation for particulate management (laser dust, grinding particulate, welding fume, etc.), but the basic idea probably wouldn’t need to be altered too much.

This design effectively broke down the typical departmental arrangement into what Kallage called “virtual cells.” Products could flow from any laser cutting machine to any press brake to any welding cell, as dictated by capacity levels, in a “single sheet” or “single tube” part flow. In this arrangement jobs could be completed in hours instead of days, just because parts would spend more time being made and less time sitting between processes.

“Tell me, is there a reason this couldn’t work?”

So asked Kevin Duggan during a breakout session at The FABRICATOR’s Leadership Summit in 2015. President of North Kingstown, R.I.-based Duggan Associates, Duggan pointed to a photo in his PowerPoint that illustrated the concept of flow in the front office. He was talking about an approach to continuous improvement called operational excellence, which emphasizes flow—that is, making sure work is flowing quickly and smoothly through all levels of the organization.

He showed a meeting area in which people sat across from each other in a line. These included people from sales, estimating, order entry, engineering, purchasing, and production scheduling. At designated times, personnel from different areas of the company—sales, estimating, purchasing, and engineering—worked together to process complicated quotes. The work literally “flowed” down the line. No longer did jobs get stuck as people waited to respond to each other’s emails. If people in estimating had a question for engineering, they just asked the person sitting across from them. The specifics behind this arrangement differ depending on the situation, but it does at least put the spotlight on the job on hand, and minimizes those time-consuming “hand offs” that make front-office work so slow-going.

Still, like technology, these process techniques aren’t proprietary. They’re not secret. Both technology and process innovations are published regularly in magazines and (in the case of Duggan’s operational excellence) books too. What perhaps sets a fabricator apart is how it uses the three legs of the stool—people, processes, and technology—to grow with customers. This changes continually with customer demand. And because it’s ever-changing, it’s probably tougher for competitors to copy.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI