Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Software tracks truth on the manufacturing shop floor

Manufacturing execution system offered as tool for continuous improvement

- By Tim Heston

- July 14, 2015

- Article

- Shop Management

An operator arrives at his workstation, which has a PC terminal next to the machine control. On the PC terminal he sees the current schedule downloaded from the fab shop’s enterprise resource planning (ERP) system. The screen shows the job, the part, and the associated machines. It also shows if and where the right tooling—punches and dies for the press brake, cutting tools for the machining center, punches for the punch press—is available. Perhaps most significant is a yellow X on the screen. That shows the downtime.

“That says if the machine is currently down. We’re integrated into the machine control, so we know in real time whether the machine is running or not.”

So said Epicor’s Marc Mailman, product manager, MEI, during Insights 2015, Epicor’s annual customer conference, this year held in Nashville in May. The event drew more than 3,700 people, and the software company touted recent changes. President and CEO Joe Cowan has been on the job for less than two years, but during that time he’s brought on a new management team, worked with Apax Partners (Epicor’s private equity owners) to spin off the company’s retail software business, and restructured the company.

“Previously, within the different business units, we had silos,” he said, “and that doesn’t make for a good experience. If I’m a customer and I’m buying different products, and I’ve got different support groups to deal with, that’s not good.”

In one sense, the real-time shop floor dashboard that Mailman described helps break down the silos in a manufacturer—at least that’s the idea. Silos lead to miscommunication, and that in turn leads to perhaps one of the biggest challenges of custom fabrication: on-time delivery.

In a recent “Financial Ratios & Operational Benchmarking Survey” from the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association, on-time-delivery averages have ranged between 80 and 90 percent. Why are orders late? Culprits abound, and one of them is knowing a machine’s true capacity level and uptime. If the schedule assumes a certain uptime, and that uptime doesn’t reflect reality, delivery challenges ensue.

It goes back to data collection and communication, and according to Epicor, this is where a manufacturing execution system (MES) may be able to help. As Tom Muth, senior manager, product marketing, process manufacturing, explained, “MES connects to equipment in real time through industry protocols. It then takes that real-time information to help schedule production on the plant floor. It understands where the constraints are, understands the equipment’s effects on production orders, and synchronizes that information with ERP.” He added that Mattec, Epicor’s MES, integrates with the company’s E10 ERP platform, but also works with ERP packages from other companies.

Central to this is overall equipment effectiveness (OEE), or the total time a machine spends making good parts as a percentage of the total time elapsed. “Manually tracking uptime often leads to overestimating the OEE,” Muth said. “Companies that have real-time systems in place can find that there’s a lot of room for improvement. Now you can identify areas where you need capacity.”

Knowing why machines are down doesn’t help much unless you know why. To this end, the system allows operators to choose a downtime reason (selected from a list, which can be customized for the user and application). In some cases, the reason is entered automatically, if existing controllers have intelligence to do so.

Connecting such software directly to machine controllers hasn’t been pervasive. If companies do use a shop management system, operators usually input job information into a computer terminal that’s separate from the machine controller. But open communication protocols may eventually change things. For instance, Epicor’s MES communicates through the Open Platform Communications (OPC) protocol as well as through MTConnect, a communication platform that has gained traction in machining and is gaining a toehold in sheet metal fabrication.

Of course, such protocols don’t work everywhere. “Most plants have a mix of equipment,” Muth said. “Getting the data [from the machine] is the first challenge.” He added that if a shop can’t connect its machines via these open protocols, be it because the equipment is old or proprietary, the company offers hardware that acts as a gateway between the equipment and MES.

Downtime information can be filtered in various ways, including by shift, by machine, by job type, and by operator. It also lists top reasons for downtime. Perhaps material or ordered parts were unavailable, or the wrong tool was selected for a certain job. Or perhaps the company was waiting for a part to come back from the custom coater.

The system also has a module for preventive maintenance. Instead of scheduling PM based on calendar days, the module can help manage and schedule maintenance based on actual machine run times. It also sends alerts to maintenance when a machine is down unexpectedly.

To put all this data to good use, the MES displays metrics that users can customize. Some may choose to display real-time OEE, some may choose to show the top five or so reasons for machine downtime. “And you can drill down across various areas of the operation—by SKU, by job, by shift, or by operator,” Mailman said, adding that with this information, users can run “what if” scenarios—predicting how improvements in one area can affect others.

Sources added that such information helps a shop not only identify areas for operational improvement, but also tells managers what kinds of jobs represent the company’s strengths and weaknesses—handy information when sales goes hunting for new business. “This gives us a more accurate view within ERP to be able to plan and manage the business,” Muth said.

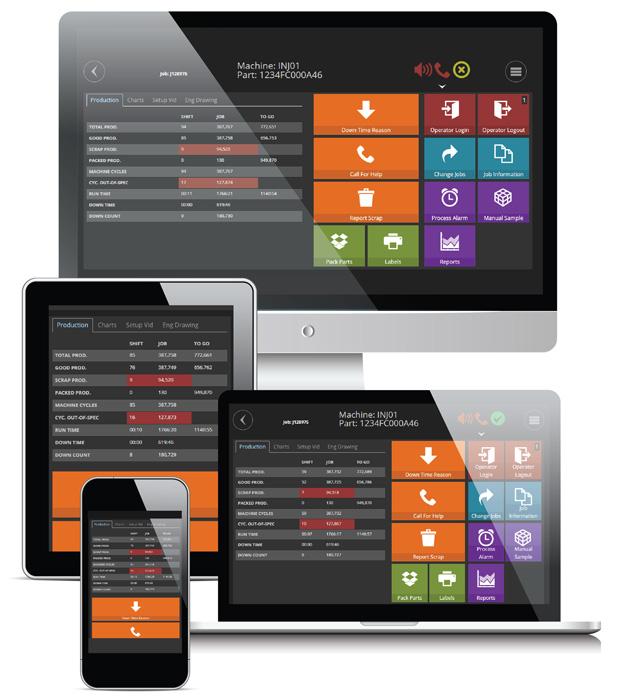

Muth and Mailman demonstrated the MES’s user interface, which is based on HTML5. This means the system can run through a web browser, which can draw information from a database in the cloud (that is, SaaS, or software as a service) or an on-site server. They added that the touch interface also helps if a shop decides to go paperless, an environment in which operators, supervisors, and managers can access manufacturing data and drawings on various devices, including a computer terminal, a tablet, or a phone.

How people interact with the software matters, but perhaps most important is showing everyone what’s really happening on the shop floor, which in turn can help people communicate. Software can’t magically help a fabricator improve its on-time-delivery performance. Tools and materials still need to be labeled, workspaces organized, part flow scrutinized, silos destroyed. But to improve, a shop also needs to measure its current state accurately and completely. According to sources, MES may be able to play a role.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI