- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Think you have a challenging bend? Bring it on

Fabricator thrives on difficult forming applications

- By Eric Lundin

- December 12, 2006

- Article

- Shop Management

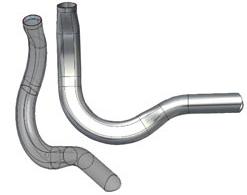

You need a simple 4D bend in 2.125-inch carbon steel tube with a wall factor of 15? Come on—that's too easy. Four 3D bends in 2.125-in. steel tube with a wall factor of 20? You can do better than that. Two 2D bends and four variable-radius bends in two planes in 2.125-in. steel tube with a wall factor of 30? And you need some of the bent sections flattened? OK, this sounds like a challenge, and a challenge is what interests Bauer Welding & Metal Fabricators Inc., a small fabrication shop in St. Paul, Minn.

Since Don Bauer co-founded the company in 1946, it has evolved into a shop that thrives on solving complex bending problems. It actually prefers complicated bending and forming and stays away from simple bending applications.

Typical Parts Are Anything but Typical at Bauer

A typical part Bauer fabricates is a one-piece motorcycle handlebar that requires two fixed-radius and two variable-radius bends. In an industry dominated by rotary bending and fixed radii, variable-radius bending is somewhat uncommon. This particular part requires bends in two planes, further complicating the process. It sounds like it would take two setups, but that wouldn't be efficient. Bauer uses a single setup on a roll bender and performs a progressive bending process called calendering.

A tailpipe for an Arctic Cat® snowmobile is another average component for Bauer, but it's not an average tailpipe. You've seen plenty of tailpipes. Some are straight and some are bent. Some have a constant diameter and some are flared. Some are one-piece and some are two-piece. You'd probably expect a bent and flared tailpipe to be made from two components, one bent and one flared. This tailpipe is a one-piece part, and it is both bent and flared, which sounds like a big pain in the neck.

Which comes first, the bend or the flare? It doesn't make sense to flare and then try to bend it—how would you load a flared tube into a bending machine? On the other hand, how would you put a bent tube into an end-forming machine? Wouldn't it be a lot easier to make this part from two pieces and weld them together?

Forget about easy.

Bauer bends the part first. Then an operator places the piece in a fixture and puts the fixture into a hydraulic press. The press delivers two strokes. The first stroke uses a flat tool that seats the part completely into the fixture; the machine then moves the forming tool into position and the second stroke flares the end.

Bauer doesn't just bend and flare. It also specializes in parts that require some amount of controlled crushing, or flattening.

Flattening a bent part can be a challenge, because the flattening process unbends it. The trick is to know how much overbending is necessary so the flattening process unbends it just enough. Finite element analysis programs aren't much help in something like this, according to Vice President and General Manager Stan Nymeyer.

"There is no mathematical equation that predicts this," he said. "You try some percentage, then add to it or subtract from it. Once you find the right amount, you're all set." Judging by the scrap rate, Bauer has it down to a science.

Bauer Welding & Metal Fabricators Inc.’s Director of Sales and Marketing William Remes shows an exhaust tailpipe the company fabricates for Artic Cat®. Bauer bends the part first, then flares it in a hydraulic press.

"It may take as few as four or five pieces before we get the right amount of bending and flattening," Nymeyer said.

"Even the distortion from the welding heat is predictable," added William Remes, director of sales and marketing.

Many of the components fabricated at Bauer end up in assemblies welded together before they leave the shop. Even though Bauer's collective experience means the finished part dimensions are predictable, the finished assemblies—often several bent tubes with welding heat and filler metal thrown in—vary slightly. How does Bauer make sure they meet the customers' specifications before they ship? The company relies on micrometers, coordinate measuring machines (CMMs), and laser tube vector systems for verifying some dimensions, but it mainly relies on check fixtures. Many, many check fixtures.

Getting a Fix on Fixtures. Bauer is more than a welding and fabrication shop. It's a machining shop too.

"We have several machining centers, so we manufacture most of our own tooling and test fixtures," Remes said.

After receiving an order for a new part, the company's machinists use the part prints to manufacture check fixtures from a synthetic composite material. As the term "check fixture" doesn't imply, they also can be used to develop or tweak the manufacturing process.

They're also used outside of Bauer. When making a check fixture, Bauer often makes a duplicate. It keeps one and sends the second one to the customer, which helps the customer quickly verify the part's dimensions.

One of the company's more challenging bent and flattened parts ends up in an intricate assembly of several bent and straight parts welded together. Because it is a complicated assembly, the company uses a sophisticated check fixture—one that has slides that the operator moves back and forth over the part to ensure that various part dimensions conform to specification and don't stick out of the fixture.

Tolerances and Part Fit-up. Bauer's variety of equipment and processes—tube bending, machining, laser cutting, and manual and robotic welding—gives it an OEM's perspective. Because the shop puts together many assemblies, it sees manufacturing the same way many of its customers see it. In other words, Bauer understands the importance of good part fit-up.

"We know what it takes for part accuracy and fit-up, so when someone orders parts from us, we know how accurate the parts have to be," Nymeyer said. For instance, Bauer supplies frame rails to motorcycle manufacturer Big Dog. The frame sections run from the steering neck to the back tire. A large gap between the steering neck and the frame section would be unmanageable for a robotic welder, so Bauer uses its bending exper-

Quality Control Inspector Jon Straight does a spot check to verify the dimensions on several parts before they get shipped to a customer. Bauer relies on several tools for quality control, including check fixtures, micrometers, and coordinate measuring machines.

tise and cutting capability to make sure the parts fit snugly. It verifies that the gap is negligible by checking the parts on a check fixture.

Homegrown Expertise

How does a company develop such expertise? It started when Don Bauer and a partner opened the business in 1946 to repair car bumpers. Within a year they were fabricating 265-gallon tanks for residential heating oil. In 1948 Bauer bought out his partner and in 1949 he incorporated the company. Exploring a new opportunity, he built a hand-powered tube bender. A small order for tubular exhaust manifolds turned into orders for tubular mufflers for small gasoline engines.

Like many entrepreneurs of that era, Bauer didn't have any sort of an engineering degree, but he had the requisite aptitude.

"He was exceedingly mechanical," Remes said, adding that he not only built machines, but wasn't afraid to modify machines he had purchased.

He had two overriding principles on which he founded the company: "Discipline and honesty are the absolute requirements for running any type of an organization successfully."

While aptitude, discipline, and honesty are crucial ingredients in the company's continued success, education plays a larger role than in years past. The engineering department is staffed by six degreed engineers. The equipment operators have either some schooling or lengthy experience at Bauer or both. The welding is performed by certified welders, and the robots are programmed by any of five certified welders who have completed a programming course.

It's more than capability, though. The company has learned to use its talents efficiently, such as how it divides the work between manual and robotic welding.

"Run size and complexity mainly determine the welds that are done robotically. If we have highly repetitive, high-volume parts, we typically put them on a robot," Nymeyer said. "We strive to maximize the output. Sometimes we use manual welding and robotic welding on the same part to reduce cycle time and maximize operator throughput. It's a matter of balancing the work load, so that neither the robot nor the worker is idle for long," Nymeyer added.

Keeping the Business in the U.S.

Although many large manufacturers have jumped on the outsourcing bandwagon and are getting parts from low-cost countries such as Mexico, China, and India, Bauer is not too concerned with losing a significant amount of business to foreign competitors.

"First and foremost is response time," Remes said. "It takes a long time for parts to come across the ocean. Second is part quality. Many of our quality standards are very tight. We can hold some tolerances that you wouldn't see on a hand-manufactured part from another country. Third, in the U.S. we have the luxury of using some of the finest materials available, and this goes hand-in-hand with making a quality part. If it's a critical vehicle component, such as a part for an ATV or a snowmobile, you have to provide a good-quality part. Fourth, we have heard stories of foreign suppliers changing specifications and not even advising their customers. Last, tubes inherently are expensive to ship. Too much air is shipped in and around intricately formed tubes, so the economics of shipping complex tubing, and the complicated packaging required to do that shipping, work to our advantage," he said.

It’s not enough to have check fixtures. They must be accompanied by instructions. Even a simple fixture such as this one has a laminated instruction page attached to it. This ensures the fixture is used correctly and that the company complies with ISO requirements.

Bauer's expertise comes into play here also. "The complexity of our parts is such that manufacturers in many other countries would have trouble replicating them," Remes said.

Even with good materials, Bauer is wary of material inconsistencies that may crop up.

"We measure everything that comes through the door for wall thickness and OD," Nymeyer said. "What you can't measure is the chemistry and the mechanical characteristics, such as tensile strength, yield strength, and elongation. Vendors provide certificates for those. Some of our customers question the price of a part, and we explain that the part cannot be made unless we buy the best material."

Despite checking incoming material and asking for mill certification paperwork, the material can vary.

"Material consistency probably is the single largest issue that you deal with in the tube business," Nymeyer said.

Controlling the raw material quality is a key aspect in controlling the finished part quality, which is crucial in preventing customers from sending the work overseas.

The Bauer Bending School

Bauer's work force has changed somewhat over the decades. Some of the old hands have retired, and while the company continues to rely on its more experienced operators to pass along their knowledge to the newer ones, some of the "tribal knowledge," as Nymeyer calls it, has been lost. The company makes up for this deficit by teaching bending fundamentals to new workers and focusing on basic principles about materials and the importance of the materials' characteristics.

"You have to develop your own bending machine operators," Nymeyer said. When the company cannot find experienced tube bender operators, it looks for applicants with the right skills and inherent abilities.

"We look for a person with a sound mechanical mind, and who can apply a little geometry and trigonometry," he added. "If the person has this sort of aptitude and is inclined to figure things out, he can probably develop into a pretty good bender."

The search for good bender operators starts before new employees get hired. The company holds pre-employment evaluations to be sure that new hires have a certain level of mathematical knowledge and mechanical aptitude.

The company's informal training program—the Bauer Bending School, as it is called by President Doug Bauer—has led to a structured training program intended to expand its workers' knowledge in math, measurement, and print-reading. Employees who pass an evaluation at the end of the class receive a pay increase and a higher potential for future merit increases. It recently developed a class that brings together the necessary elements—math, bending principles, print-reading, and fundamentals of metals.

That aside, the company has to keep a close eye on incoming materials to be sure that all the training doesn't go to waste. "Many people don't realize that many parts are right on the edge, and that's why these projects are so material-sensitive," Nymeyer said. "If you buy tubing and all you're going to do is cut it, it really doesn't make much difference what you buy, as long as it's dimensionally correct. But if you're doing tight-radius bends, material will make it or break it."

The company even conducts a short training class on customers' premises, so that the customers' design engineers get a better understanding of the capabilities and limitations of various manufacturing processes. Dispersing this type of knowledge helps prevent engineers from designing products unnecessarily difficult or impossible to manufacture, or on the edge Nymeyer mentioned.

On the other hand, the company continues to add to its knowledge base by taking on difficult jobs. Nymeyer acknowledged that on occasion the company takes on a project that simply doesn't work out. Surprisingly, this actually works in Bauer's favor. Getting out of its comfort zone and taking on difficult jobs help the company to increase its collective knowledge base. The company learns something from every project, regardless of the outcome.

About the Author

Eric Lundin

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8262

Eric Lundin worked on The Tube & Pipe Journal from 2000 to 2022.

About the Publication

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Team Industries names director of advanced technology and manufacturing

Orbital tube welding webinar to be held April 23

Chain hoist offers 60-ft. remote control range

Push-feeding saw station cuts nonferrous metals

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI