Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

What brings youth to the sheet metal business?

Young workers at a custom fabricator and a roll former share their insights

- By Tim Heston

- March 31, 2016

- Article

- Shop Management

Figure 1

Pat Hopkins, 30, didn’t necessarily plan to have a manufacturing career. But after interacting with co-workers and learning the business of roll forming, he changed his mind.

A recent college graduate lands a job at a large corporation. His first day he undergoes the typical new-employee orientation, complete with a highly polished corporate video. Then the next day he sits in his cubicle, answers e-mails, and starts his work. Hours later he stands up, finally, and goes to lunch.

Now consider a two-year technical school graduate who lands a job with a contract manufacturer. He arrives at a custom fabricator and gets oriented, but in this case he actually talks to people. He talks to the press brake operator who has been with the company for decades. He talks with an estimator who knows every aspect of every process inside and out. He talks with the operations manager, a guy with some stories to tell. He goes to lunch with co-workers and somehow feels like he’s been working at the place for months.

You can probably guess which situation has the happier employee.

John Green, author of popular youth novels like Looking for Alaska and The Fault in Our Stars, described (in a YouTube post) how young people face challenges when they enter the workforce. One aspect is financial, though that depends a lot on one’s family situation and personal circumstances. But he also mentioned another challenge that’s more universal: “The crushing monotony of it all.”

Decades ago a so-called “good” manufacturing job was the epitome of monotony: Put a sheet metal blank in, cycle the press, take a formed part out, repeat. Certainly, those jobs still exist in places where automation doesn’t make sense, but those situations are becoming few and far between.

High-mix, low-volume production, a highly variable business, dominates U.S. manufacturing. Even high-volume OEMs must deal with frequent model changes. In these environments people talk, schedules change, part designs change, and the shop floor adapts. For a young person, that’s an engaging place to start a career.

This month The FABRICATOR spoke with two people who serve on the Young Professionals’ Council of the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association International. Both grew up in manufacturing families, though neither necessarily considered a manufacturing career as a given.

The Broad View

Manufacturing is in Pat Hopkins’ blood (see Figure 1). His father is a 43-year veteran tool- and diemaker. Still, Hopkins didn’t grow up dreaming about a manufacturing career. He knew how hard his father worked.

“I remember my mom would take all five of us kids to lunch at my dad’s shop, and I do have fond memories of seeing my dad and his co-workers. But he worked so hard for his family. He worked 10-hour days, and in the back of my mind—I have to be honest—I didn’t think it was something I wanted to do.”

The internship at his dad’s company changed his perception. “When I was in high school, my dad wanted me to look at the font-office side of the business. He wanted me to get the entire view of manufacturing.”

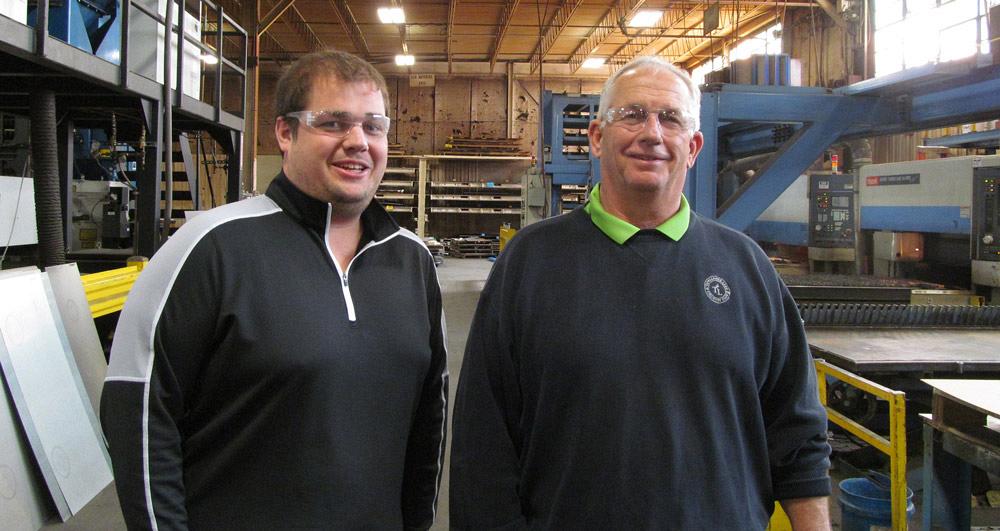

Figure 2

Ben Wiley, 27, and his father Ed Wiley, president of Wiley Metal Fabricating, talk a lot about the shop’s history. When Ed started in the early 1980s, metal fabrication was a different world.

During the internship, Hopkins cold-called sales leads, talked with steel suppliers, and helped in the estimating department. He talked with other front-office personnel, the operations managers, the machine operators, the CEO and senior managers—a cross section of the entire organization. “And they all have to work together to make a good product,” he said.

He added that only after the internship did he truly appreciate how multifaceted his dad’s job really was. “He’s in the forging industry, and when I interned, I saw him work with all the guys who worked on the forging presses. He had to work with various aspects of the business. He worked with the engineers and proposed different ideas on how to tweak designs. I didn’t really know this until I actually spent time with my dad in the shop.

“[The internship] taught me that there are great jobs in manufacturing, jobs I never even thought about,” he said. “Guidance counselors really should present kids with all the different career options. They want people to be investment bankers and sports agents. But manufacturing is an option, and it does kids a real disservice not to present it as one.”

Still, Hopkins admitted that, even then, he wasn’t necessarily set on the idea of having a career in manufacturing. But the experience did instill in him a curiosity and engagement that so many employers crave.

Out of school, he held a sales position in the food distribution business before landing a job in sales at roll forming tooling supplier Roll-Kraft. He saw the job not as a way to get his foot in the door in manufacturing, but simply as an opportunity.

“I believed any experience is good experience,” Hopkins said. “Before then I really had no idea what roll forming was.” He added that the company sent him to roll forming seminars and took him through every aspect of the process, from engineering to machining and welding to the shipping department. He reiterated that learning that entire process really was key to getting him hooked on the manufacturing business.

Then came the opportunity at OMCO, a custom roll former in Wickliffe, Ohio, where Hopkins now works as a project manager in the estimating department. Brian Duffin, OMCO’s director of estimating, remembered thinking Hopkins would be a good fit just from talking with him on his first day. It wasn’t just because of his previous experience with roll forming tooling, though that certainly was a plus.

“I could see he had a great attitude and positive energy,” Duffin said. “I knew he was really going to jump into his role well.”

Hopkins entered the roll forming business at a time of change. The process remains somewhat of an art; material batches of the same grade and thickness may have slightly different tensile strengths and thicknesses, so it’s still up to the roll form operator to get a feel for a piece to form it up correctly. What has changed is the software, and here Duffin said that Hopkins has pushed for more advancements.

Hopkins chimed in. “CAD is miles ahead of how it used to be. I was at a tradeshow a few weeks ago and witnessed some of the new 3-D modeling capabilities out there. It’s just incredible.”

Nevertheless, Hopkins conceded that roll forming isn’t like other manufacturing processes. It’s difficult to break it down into 1s and 0s. “It’s still really difficult to cost-effectively simulate the black art of roll forming. The process still requires tryout, and it all comes down to feeler gauges, calipers, and old-fashioned estimating with a paper and pencil.”

Hopkins performs a balancing act between knowing and respecting what came before, and a curiosity about future efficiency, be it gained with new software or anything else. He achieved this balance, he said, thanks in part to OMCO’s onboarding process and in part thanks to his job responsibilities. To do his job well, he needs to talk to everybody in the business: engineers, machine operators, purchasing managers, and more.

He also has mentors, including Duffin and OMCO’s Director of Engineering Roger Norris. They and others have helped him succeed in his career, and not just because of the knowledge they impart.

Long-term mentoring helps veterans to, as Hopkins put it, “see young people not as replacements, but as the future. At a lot of places in manufacturing, a lot of experience isn’t being passed down, and companies are left without a contingency plan.

“The youth need to be mentored rather than schlepped into a job with an experienced person, with managers saying, ‘OK, here’s your replacement,’ like it’s some changing of the guard. We need a continuum of training, with people who are in their 30s training people who are just entering the workforce; and people in their 50s training those in their 40s, 30s, and 20s.”

Hopkins grew up around the advanced machinery of modern manufacturing, but it wasn’t the technology that helped him thrive. It was the fact that he doesn’t spend his days in a cubicle as an isolated cog.

About the Team

“It’s about the people more than anything and seeing them come together as a whole—people from shipping, production, and customer service. It’s the teamwork aspect of it all, and everyone coming together for a common goal. There’s more to it all than just making things out of metal.”

You might think that comment came from Hopkins, but it didn’t. It came from Ben Wiley, a fellow FMA Young Professionals’ Council member and production supervisor at Wiley Metal Fabricating (see Figure 2).

Wiley’s story is remarkably similar. Like Hopkins, Wiley has manufacturing in his blood. His grandfather launched the Marion, Ind.-based custom fabricator in the 1980s. In high school and even through much of college, Wiley also didn’t see manufacturing in his future.

“I went to college to become a golf pro and really didn’t have much interest in the business,” he said. “But then I had an internship during my junior year, and I fell in love with the place. It really changed my path, so I came back to work here after I graduated.”

The fab shop is preparing for ISO certification, mapping all processes from the initial order to final shipment. This, Wiley said, is helping employees see the big picture and appreciate everyone’s role. They’re also gaining a sense of what purpose their fabricated components serve in the end products. “Employees recognize when they see parts on a trailer,” he said. “They see their work on the end product, and they can turn to their spouse and say, ‘I did that.’ There’s pride in that.”

Much has changed since Wiley’s dad joined the family business in the 1980s. “We have this conversation often,” Ben Wiley said. “Back then they really flew by the seat of their pants.”

Today, of course, is entirely different. Customers want maximum efficiency in their assembly, and to achieve that they need maximum precision. “Now the tolerances and pricing are a lot tighter,” Wiley said. “We really need to run through our metrics carefully. Everything is a competition.”

With this has come new technology that has eased the act of cutting and shaping metal, including offline brake programming and modern nesting software.

Machines still require some skill. But beyond operating a machine, shop floor employees need to have a wide-angle view, Wiley said, hence the value in flow charts, mapping processes, and continuous improvement. Just this year the company implemented an idea-generation program, and already managers are considering a half-dozen new approaches to old problems.

Retention Is Key

Custom fabrication (and all of manufacturing) must work to not only attract talented and engaged youth to the profession, but retain them as well. At Wiley, the shop’s recent improvement initiatives are having an effect.

Having employees with varying ages and years of experience can help create that continuum of training and mentoring. Combined with the right technical educational programs, like nationally recognized certifications, this continuum of training and mentoring actually may, at least in some places, make the skilled-labor crisis a thing of the past.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI