Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Freeing space for metal fabrication

Illinois stamper cleans house with plans to expand into cutting, bending, and arc welding

- By Tim Heston

- October 19, 2015

- Article

- Bending and Forming

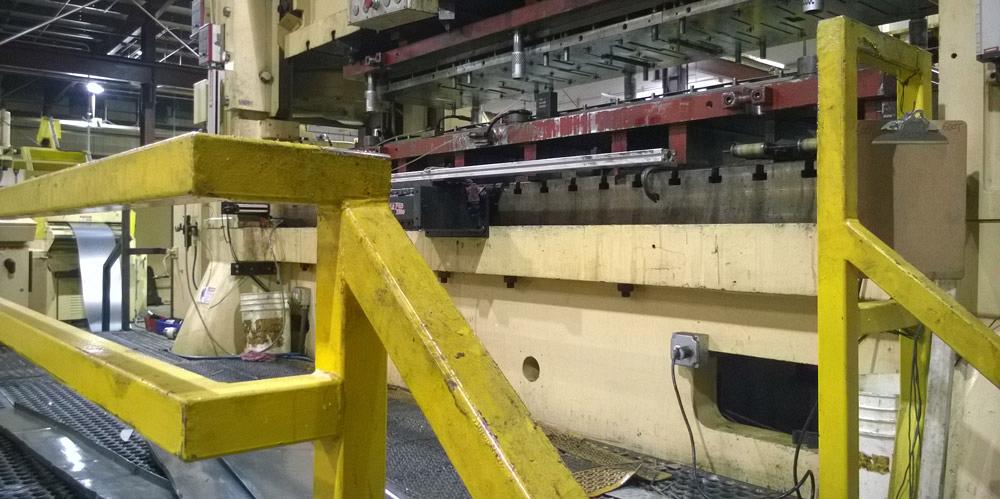

Figure 1

This recently cleared space at Performance Stamping

probably will house lasers, punch presses, and press

brakes as the company begins its expansion into metal

fabrication.

The people at Performance Stamping have uncovered space in the plant, and they don’t aim to fill it—at least not in the old way.

They could fill it with stamped components easily enough, and years ago that’s probably what the Carpentersville, Ill., stamper would have done (see Figure 1). All those stamped parts were a result of running coil-fed mechanical presses for as long as possible without changeovers.

The company has stamping presses with capacities from 22 to 600 tons and up to 144-inch beds. Parts discharge into bins, and conveyors under the floor carry what’s left to the large scrap container at the west end of the facility. The plant has a centralized system that feeds lubricant as needed to every press. Coils come in, parts come out, and the churn continues.

Of course, running presses for a long time created large batches, which in turn created large amounts of work-in-process (WIP) and, ultimately, finished goods inventory. Inventory led to clutter, which led to haphazard floor conditions. Pedestrian walkways weren’t clearly marked or were simply nonexistent, which meant people were dodging fork trucks left and right. (And more often than not, the drivers didn’t receive proper forklift training.) Platforms around presses and at the loading dock lacked railing.

Dies were stored several deep in racks, which made it difficult and time-consuming to retrieve them. When they did retrieve them, setup people couldn’t perform changeovers in a uniform manner across all presses. The company had upgraded one press for quicker die changes (QDC), but it didn’t improve matters significantly, because it made the operation less versatile. Parts were everywhere. Practices weren’t standardized. Batches were massive. On-time-delivery rates suffered.

So what came into Ken Keafer’s head when he started at the shop late last year as the new director of operations? Metal fabrication. The company already performs spot welding for certain product lines (see Figure 2 ), but Keafer is looking to expand more into full-service contract work involving laser cutting, bending, and arc welding.

Keafer is a Six Sigma Black Belt who has experience in high-product-mix production at various plants, including facilities specializing in metal fabrication. He worked previously with David Maxwell, who four years ago moved on to become president of Performance Stamping. Maxwell had been hoping to get Keafer onboard, and a position finally opened up late last year, so Keafer took the opportunity.

Why did he take the job, especially considering all the company’s problems? Part of it was the shorter commute. Part of it was the very fact that the company had excess inventory and tools, and he knew that once they were gone, he’d have a blank slate to work with. A blank slate has a lot of potential.

In that space he saw lasers, press brakes, as well as more welding and assembly in Performance Stamping’s future, not just because he has experience with the technology, but because the technology will help broaden the company’s current customer base.

It’s not an unusual game plan for many stamping houses these days. Offering both fabrication for low volumes and stamping for high volumes allows a metal manufacturer to follow customers through the product life cycle, from prototyping through production and aftermarket support.

Figure 2

These parts are prepped for automated spot welding.

The company does perform spot welding through traditional

means (rocker arm resistance welders) and automated

setups. It has yet to expand into other areas of

fabrication, but this is set to change.

Before bringing in equipment, though, Performance Stamping first needed to clean house and improve safety training, part flow, and inspection practices. When the company brings in its metal fabrication, the second act can begin; this year, though, Keafer and his team have been busy setting the stage.

Safety and Accountability

The first set pieces on stage involved new approaches to safety and accountability—and safety was at the top of the list. “The mindset here was that people didn’t care about safety,” Keafer said. “All they cared about was production going out the door. So the first thing we did was to get everybody to slow down and understand that safety was a priority in the organization.”

The company designated certain lanes for fork trucks. An outside firm came in to perform forklift training and certification. “So now everybody is documented,” Keafer said. “Nobody’s allowed to drive a forklift unless they’ve been certified. We’ve done similar training and certification for crane operation. And now everyone needs to wear hard hats. It’s really been about changing the mentality.”

The stamper cleaned and painted the floor using a grit-based paint for slip prevention. They installed railings on the press platforms (see Figure 3) and by the shipping and receiving dock. They also installed a hydraulic lift on the shipping dock, making it safer and easier to load parts onto trucks. And now people are trained to identify and, if possible, correct safety hazards when they see them. For instance, if an employee sees a draw-oil or any other kind of spill, he cleans it up right away.

To address the accountability problems, Performance Stamping revamped the org chart. After all, it’s difficult to change a company plagued with silos, where finger-pointing is rampant.

“The toolroom blamed production for all the issues going on; production blamed the toolroom for not getting the tools back in time. And nobody owned quality except for the quality department,” Keafer said. “People would say, ‘It’s the quality department’s responsibility to sign off and determine whether a part was good or bad.’”

The toolroom reported to engineering, while production and shipping and receiving reported to the director of operations. To eliminate the silos this created, production, shipping and receiving, and toolroom personnel now all report to the director of operations.

The company also follows a new preventive maintenance (PM) regimen. Previously maintenance was mainly reactive. If a tool produced bad parts, it was sent to maintenance for repair. Now tools are sent to PM at regular intervals after operations. “In our new system, after so many hits on a tool are recorded, the system will create a red work order that is sent to the toolroom,” Keafer said. The idea is for tools to be inspected and repaired before they have a chance to produce bad parts.

Moreover, everyone on the floor is now involved in quality, and setup personnel periodically check parts. “We’re eliminating floor inspectors,” Keafer said. “Instead, we’re migrating all inspection functions to setup personnel and supervisors. The quality group will be auditing the process. If a person sets up a job, he or she should be able to inspect and improve it.”

Clearing Space for Improvement

Over a period of months the shop reduced WIP and finished goods inventory dramatically, an act alone that has freed up enough space for a few lasers and a press brake. The company threw out old tools that customers didn’t use anymore, and it cleared out some old machinery.

“I don’t like hiding spots,” Keafer said. “If you have a lot of racks, then you have too much inventory.”

Previously racks for tools were two or three stories high and two piles deep. Over the course of several months, the company eliminated double-racking and made everything accessible at floor level, which is obviously quicker as well as safer—no more reaching high into the air with a fork truck to retrieve tools.

The company needed all these racks, of course, because of the way it ran its presses: in large batches. “They would run 100,000 parts, and they didn’t care if those parts would sit for 10 months,” Keafer said.

The company now produces on demand. It does keep safety stock for certain larger customers, but those stock levels are tightly managed, complete with set reorder points. Production is triggered only when stock drops below a certain level; no longer do machines run for hours just to avoid a setup.

The setups themselves are more predictable, thanks to the PM regimen in place. Keafer added that further QDC improvements are coming, including the standardization of die-change technologies and procedures across all presses.

To improve part flow, Keafer separated out certain lines, including a stamped and welded assembly produced for one of its larger customers, to a smaller building the company owns across the street. There the assembly is produced, inspected, and shipped all in one location (see Figure 4).

“We’re staging FIFO [first-in first-out] lanes for two weeks’ worth of product on the floor,” he said. “It’s all become very visual.”

Cultural Shift

Keafer conceded that initially employees resisted the change. “A lot of people weren’t sure how far this improvement effort was going to go, because they had seen initiatives like this start but never go anywhere,” he said. “It’s something that happens in every organization. But once we started to make progress in certain areas, people started to buy in. It isn’t just a fad. It’s something that’s exciting, and everybody is onboard, because they’re a part of it.”

The last point, about people being part of the process, is critical. Keafer said this while pointing to a new issues board posted on the shop wall, which details the status of safety, 5S, inventory, productivity, quality, and delivery. Once a day an employee from every department meets by this board, which uses a simple color-coded system. Green means that all goals are being met; yellow means things could use improvement; red means that serious problems exist; and blue means that nothing active is in the area to measure.

Outside the blue “not applicable” color code, the rest would be subjective without concrete definitions, and so the company posts them right next to the status board. For instance, a yellow color in the productivity area shows that less than 80 percent but more than 70 percent of scheduled work has been completed, while red shows that only 70 percent of the work or less has been completed (see Figure 5).

Most important: Employees on the front lines—the people who do the actual work—created the system and determined what should be on it. “They all did this,” Keafer said. “They created it, and they own it.”

Space Equals Potential

It’s difficult to develop and train a highly motivated core workforce in an environment where some people are here today and gone the next. So one of Keafer’s first acts as director of operations was to eliminate temporary workers.

“I wanted to be sure we could develop the core group of people we have here,” he said, “and I wanted them to grow with the company, so they need to be permanent employees.”

That said, today the company employs 56 people, fewer than it has in the past, but it also has eliminated an entire shift of operation. “Our head count is down overall by 11 people, yet we’re still producing the same volume as we did before,” Keafer said, “and we’re more profitable.”

At this writing, space is clear in one facility for more fabrication. Soon Performance Stamping will have several empty rooms in its adjacent facility, plenty of room for a few fabrication cells: a punch or laser, a few press brakes, perhaps even a robotic welder. Keafer added that he may bring in more automation than a traditional fabrication start-up does. It again goes back to space; the more the company can get out of less space, the better.

Of course, what the company’s fabrication investments will be depends on the business the company wins. As Keafer put it, “Once we get these bays empty, we can bring customers through and talk about their business and say, ‘We can do your business right here.’”

In less than a year, the stamper and aspiring fabricator changed how people perceived space. It’s not a place to put current work, and it’s not for inventory. Empty space can instead become productive space, and therein lies potential.

Figure 5

Once a day someone from every department meets by this board, which details the status of safety, 5S, inventory, productivity, quality, and delivery. Next to this board is a key describing exactly what each color means. Staff also have the opportunity to record and communicate any problems they may be having in each area.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI