Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Hydraulic presses make their mark

- By Lincoln Brunner

- September 25, 2003

- Article

- Bending and Forming

|

Just like hydraulics technology itself, the market for presses based on it is fluid and dynamic. And for the first time in a while, the tide may be turning in favor of its practitioners.

As many manufacturers report prosperity and strong prospects for it in the near future, the hydraulic press market is leaping into customization like never before while pulling its collective hair out over a skilled labor shortage that only promises to get worse if forceful measures aren't taken.

Press builders note the age-old demand for ever-increasing strokes per minute (SPM) and faster die changeover times, more sophisticated data acquisition technology, and more advanced controls. For example, Bud Graham, president of Welded Tube Pros LLC, Doylestown, Ohio, noted that the optical encoders used to deliver direct readouts of hydraulic piston strokes suffer none of the effects of temperature variations that older measurement technology did.

"From our standpoint, on the control side, the position and force capabilities I think have improved," Graham said. "We can tell at all times what forces are being exerted."

Press builders also are reveling in hydraulic presses' increasing share of the press market.

"I think the acceptance of hydraulic presses by some of the younger engineers is fantastic," said Paul Pfundtner, owner of Red Stag Engineering & Automation, Waupaca, Wis. "I think that hydraulic presses are becoming more and more acceptable in the marketplace. The types of pumps and valving have advanced—there are a lot of advances in that area that are very beneficial."

That is translating into dollars, said other builders.

"There's been a significant increase in the use and purchase of hydraulic presses," said Mike Hamilton, president of Magnum Press Automation, Jerseyville, Ill. "People are now understanding the capabilities of hydraulic presses, and because [the presses] are getting faster, they can use them in more applications."

Jeff Carson, vice president of sales for Samco Machinery Ltd., Toronto, can testify about speed, a characteristic once exclusively linked to air and mechanical presses.

"Historically ... hydraulic was always the slowest," Carson said. "Now things have been stood on their head: Hydraulic is the fastest now and still gives you 100 percent tonnage all the way through the stroke. Depending on the application, we have presses here firing 200 strokes per minute. That's a major change."

Perhaps it's that kind of technological improvement that contributed to many companies' better fiscal fitness at the beginning of this year.

Economic Turnaround?

"I'm getting pretty optimistic," said Dan Wolbert, vice president of Savage Engineering Inc., Garfield Heights, Ohio. "We may not be heading back to 1998, but I think we're headed in the right direction. I'm much more optimistic about the economy."

Savage, a manufacturer of presses for everything from compaction of powders for smart-bomb warheads to steel plate straightening, had received orders for six presses in the week before Wolbert was interviewed. Granted, those orders were a long time in coming, but business is business. And business has been good, say some other industry players.

"Things are actually pretty darn good," said Vance Hays, vice president of Standard Industrial Corp., Clarksdale, Miss., which does a substantial amount of its business with large suppliers of leading automotive and airline companies. "I believe the bigger companies see it turning around, and they're placing orders with their suppliers; then their suppliers are buying from us."

Likewise, Carson has seen sales perk up and hears the same from his customers, 90 percent of whom are in the U.S.

Others don't see such a rosy tint to the picture.

"Right now everything is slow," said Kenneth Frick, sales manager at Roto-Die Inc., Euclid, Ohio. "It's really spotty, actually. One month it looks like it is going to pick up and go, and the next month it falls flat again. There's no consistency at all."

Times being what they are, Frick said his company is just trying to focus on keeping costs down for his customers, most of whom serve the heating and air-conditioning industry with fabrication of light-gauge sheet metal.

Likewise, Walter Davic, president of Penntech Industrial Tools, Cranberry Township, Pa., said his company has thrived on supplying low-tech gap-frame hydraulic presses to shops that need to replace mechanical units for safety reasons or to run secondary, hand-fed stamping operations.

Tax Boon. Davic noted that the biggest problem machine builders face right now is lack of management approval for capital investment in the past 18 months. However, recent changes in depreciation guidelines in the federal tax code should be a boon to small businesses looking to invest in capital equipment, he said.

The new Section 179 guidelines for asset expensing, with certain qualifications, give companies a huge bonus by allowing them to depreciate 50 percent of capital equipment placed into service after May 5, 2003, up from 30 percent under the old law, plus the first year's worth of depreciation on the traditional seven-year schedule (an additional 14 percent). More important, Davic said, the new Section 179 guidelines allow a small business to write off up to $100,000 (up from $24,000 in 2002) in capital equipment purchases the first year.

"That was what we believe will provide the biggest positive impact to our business short-term," Davic said of the latter provision.

I'll Take One of These, Two of Those ...

Futurists looking at manufacturing once talked of an era of mass customization, in which no more standard products would be made and customers instead would dictate production and scheduling.

If hydraulic pressmakers aren't living that already, they're headed there fast.

"The last two years, commodity presses haven't been selling; if we weren't selling custom presses, we wouldn't be selling anything," said Tom Wendell, principal engineer at Greenerd Press & Machine Co., Nashua, N.H. For Wendell and company, that has meant developing presses with custom speeds and auxiliary equipment.

On the flip side, Schuler Inc., Canton, Mich., has seen among many of its customers a move away from customized equipment, a company representative said.

"Especially in the tier industry, we see a trend to standardization rather than to customization," Schuler's Andreas Kinzyk said. "Today customers look for a wide variety to choose from, but customization always has its price tag, and nobody wants to pay for extras." After studying those customers, Schuler developed its ProfiLine for transfer presses and tandem lines based on a modular concept, Kinzyk added.

Lead-time. If custom specifications weren't enough, buyers also are demanding less and less lead-time—from 12 to 16 weeks a few years ago down to eight to 10 now, Wendell said. How do they handle that?

"We don't sleep at night," he joked. Actually, it's meant a paradoxical move toward more standardization in-house: modular designs that allow Greenerd to use components it already has on hand to build machines.

"Part of handling shorter lead-times is passing along demand to our vendors," he added. "It gets passed down the chain."

It also involves quickening every stage of in-house processes, said Gordon Baker, vice president of product technology for Pacific-Press Technologies, Mount Carmel, Ill.

"I think no matter how short it is, they want it a little shorter," Baker said of lead- times. "We've done a lot of work to keep lead-times down, [and it's] kept us in a number of deals. I would say in the last five years, we've probably taken around 40 percent of our lead-time out."

Baker noted that Pacific also gets a lot fewer orders for general-purpose machinery and more for particular part applications. The company has responded by adding feed systems and trying to match line speeds with particular sets of tooling.

One thing that doesn't help is having to compete with foreign press builders whose governments underwrite stocking programs that allow them to turn machinery out faster than North American builders that enjoy no such advantage, said Matt Driessen, general manager at Brown Boggs Foundry and Machine Co. Ltd., a builder of custom hydraulic presses in Ancaster, Ont.

"They [customers] take a year or better to decide, and all of a sudden, they want it yesterday," Driessen said of the turnaround demands. "It puts North American [machinery] builders at a disadvantage. Delivery certainly is always an issue. Obviously, we have to pay for our own materials. The word on the street is that some of the others are looked after by their own governments. It would be nice if our government did that; the reality is, it doesn't work that nicely."

Speed. Being responsive means coming up with solutions when customers come to you with a part they need built, said Rainer Egelhof, account manager for Muller Weingarten Corp., Madison Heights, Mich. It also means responding to advances in competing technologies, such as mechanical presses.

"Everybody on the hydraulic end needs to try to keep up," Egelhof said. "Even though hydraulics are much more flexible, you've still got to get the throughput; you've still got to get the strokes per minute. That's the thing everybody is looking for; that's what makes them money."

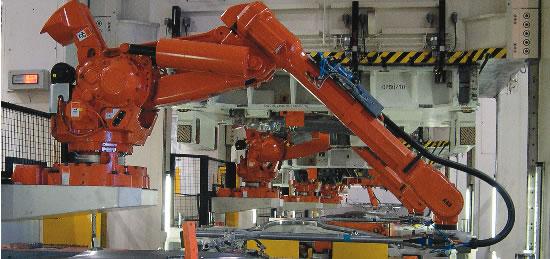

Hence, Muller Weingarten is quoting full turnkey systems and focusing on automation between presses—even purchasing and installing other companies' automation systems into their press lines, if need be.

Andy Kirk, president of Macrodyne Technologies, Concord, Ont., said the trend toward lower-volume work has made the flexible hydraulic presses and the quick-change die systems his company carries all the more attractive, simply because customers want jobs turned around on a dime.

"Nobody's willing to pay for inventory these days," Kirk said.

Manfred Bruemmer, sales manager for Dieffenbacher North America, Windsor, Ont., said one strong trend among his customers' requests is for so-called tryout presses—sophisticated hydraulic presses that simulate the behavior of mechanical presses. These tryout presses can be used for die spotting and can produce parts with speeds equal or nearly equal to mechanical presses.

"These presses have extremely high speeds [for] a hydraulic press," Bruemmer said. In addition, setup time for tools and dies in a transfer line is reduced, he said.

Another trend Bruemmer sees is increased use of hydraulic transfer lines among manufacturers of automotive aftermarket parts because of the flexibility they offer. "Setup times are very flexible, insofar as hydraulic preadjustment of ram and stroke can be programmed on-screen in the computer," Bruemmer said.

Magnum's Hamilton reported that business has picked up tremendously this year for his company, and that the best thing anyone could do right now is offer products that meet product specifications, but especially time demands.

"Everybody is waiting until the last minute to spend their money; so when they do call, they want it in a timely fashion," Hamilton said.

While Magnum has responded with digital controls and data acquisition software that allow project engineers to observe and regulate machinery on the floor, Cincinnati Incorporated has responded with quick die change systems that allow fabricators to focus on efficient, shorter runs.

"It's a tougher market out there now," said Todd Kirchoff, product manager for Cincinnati, which builds hydraulic presses exclusively. "A lot of stampers ... are to the point where they're losing business overseas you normally wouldn't think would go. The longer-run type of work, they're losing some of that. They have to be more efficient."

That focus certainly involves being able to slide and clamp dies fast, but also being able to recall computerized job programs quickly so that setup is consistent with the previous job.

"This is not a radically new concept, but in this type of economy, it is something people want to talk more about," Kirchoff said.

Using Your Data. Like Magnum, Air-Hydraulics Inc., Jackson, Mich., believes in supplying data acquisition technology to its press customers, said National Sales Manager Todd Bell.

"A lot of customers come to us and want to know how much force they're exerting, the distance exactly that the press ram has moved down," Bell said. "They want data acquisition on that so they can supply that to their customers, so they know they're making acceptable parts.

"Very seldom do we sell too many standard products anymore," Bell added. "A press just isn't a press anymore; it needs to almost work for itself, in a sense, from a control standpoint, from a gauging standpoint."

Looking for Labor

Standard Industrial's Hays noted that right behind the perennial problem of steel costs is the fight for good help. He's been advertising for a machinist almost constantly in area newspapers for three to four years and wants engineers too.

"Skilled labor is always the toughest to find," said Hays, who figured the problem was worse in his local area in the Mississippi Delta region. "Right this minute I have a dire need for engineers—at least one, probably a couple."

Roto-Die's Frick finds machinists scarce as well.

"Right now machining is starting to be a dying trade," Frick said. "It's hard to get a good machinist, really." And with many machinists working to age 70, he's not afraid to hire a 60-year-old with skills.

"You're hiring a lot of experience there," Frick said.

The skilled labor problem is systemic, according to Penntech's Davic.

"It starts at our basic schools," said Davic, who reported that a very large percentage of applicants at many of his customers' businesses cannot even read the markings on a ruler properly. "Kids leave high school not knowing how to read and write.

"In the next 10 years U.S. manufacturing companies are going to be faced with a hypershortage of qualified labor," he added. "Not skilled labor; I'm just talking qualified labor."

What to do? Well, bring back in-house apprenticeships, Brown Boggs' Driessen suggested. As evidence of their success, Driessen noted that workers from apprentice-rich western European nations qualify for his open positions.

"Apprenticeship programs are not in place here to attract younger people to come into the trades," Driessen said. "There's certainly a stigma attached—nobody wants their little boy or girl to be a factory worker."

However, as the baby boomers age, manufacturers have a limited number of choices: import labor, outsource, or raise your own.

"Certainly, some in-house apprenticeship programs is what we'll have to do," Driessen added. "We really don't have an alternative, other than subcontract. Then you're paying someone else's overhead instead of absorbing your own. You have more control of your costs in-house."

John Murphy of Neff Press, St. Louis, does not see a shortage of skilled labor thanks to recent higher unemployment rates, but does see perhaps a need for better mentoring programs."I do notice delineation between shop personnel and the engineering department," Murphy said. "There tends to be reliance on the engineering department to handle tasks that might have been handled by shop personnel 20 years ago. One fix to this problem might be involvement with some mentoring programs or hiring individuals who have been through some apprenticeship class for shop positions."

In addition, businesses must invest more in training the people they have, Muller Weingarten's Egelhof said.

"That's where everybody seems to skimp a little bit," said Egelhof. "If they would [only] realize if you have untrained people, your output suffers considerably.

"Everybody can do that–Dieffenbacher can do it, Schuler can do it. But the end user has to spend the money to do it. There are people out there, but the equipment we're building is more advanced than it ever was. You've got to get these people you have trained, get them updated. Every six weeks, have one day of training to refresh the knowledge of the people. That would help a lot."

While Pacific's Baker agrees, he also noted that many shops are moving toward less physical work in press shops—processes that run with less labor required.

"There is a shortage of what I would call skilled labor from the standpoint of operation of machinery," he said. "Customers are moving more toward machines that can be programmed, even offline programming."

Those advanced controls, in turn, can be run by people with fewer skills, Kirchoff noted.

"The advantage to buying a machine is that you can trust the machine setup is right without having a journeyman-level [person] set it up," Kirchoff said. "If you can have a less skilled person you can trust setting the machine up, that is a big jump in efficiency for you. We have seen that in press brakes and presses. It works both ways.

"It's hard to get the young guys interested," he added. "They don't want to get into manufacturing. Dad worked at the plant for 30 years and lost his job. That talent pool is getting tougher."

Air-Hydraulics Inc., www.airhydraulics.com

Brown Boggs Foundry and Machine Co. Ltd., www.brownboggs.com

Cincinnati Incorporated, www.e-ci.com

Dieffenbacher North America Inc., www.dieffenbacher.de

Greenerd Press & Machine Co., www.greenerd.com

Macrodyne Technologies Inc., www.macrodynepresses.com

Magnum Press Automation Inc., www.magnumpress.com

Muller Weingarten Corp., www.mwcorp.com

Neff Press Inc., www.neffpress.com

Pacific-Press Technologies, www.pacific-press.com

Penntech Industrial Tools Inc., www.pghntma.org/penntech.htm

Red Stag Engineering & Automation Inc., www.redstag.com

Roto-Die Inc., www.roto-die.com

Samco Machinery Ltd., www.samco-machinery.com

Savage Engineering Inc.,

href="https://www.thomasregister.com/olc/savage/">www.thomasregister.com/olc/savage/

Schuler Inc., www.schulergroup.com

Standard Industrial Corp., www.STANDARD-INDUSTRIAL.com

Welded Tube Pros LLC, www.weldedtubepros.com

About the Author

Lincoln Brunner

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

(815)-227-8243

Lincoln Brunner is editor of The Tube & Pipe Journal. This is his second stint at TPJ, where he served as an editor for two years before helping launch thefabricator.com as FMA's first web content manager. After that very rewarding experience, he worked for 17 years as an international journalist and communications director in the nonprofit sector. He is a published author and has written extensively about all facets of the metal fabrication industry.

Related Companies

- Brown Boggs Foundry and Machine Co. Ltd.

- Dieffenbacher North America

- Greenerd Press & Machine Co. Inc.

- Macrodyne Technologies Inc.

- Magnum Press Inc.

- Neff Press Inc.

- Pacific Press Technologies

- Red Stag Engineering & Automation Inc.

- Roto-Die - A Member of the Formtek Group

- Samco Machinery Ltd.

- Savage Engineering and Sales Inc.

- Schuler Inc.

- Standard Industrial Corp.

- Welded Tube Pros

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI