Contributing Writer

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Die Science: Piercing, cutting aluminum without slivers

Stopping sliver formation

- By Art Hedrick

- February 22, 2018

- Article

- Bending and Forming

Figure 1a and 1b - Insufficient clearance during cutting creates compression deformation (top), while excessive clearance creates tensile deformation.

I have had a few consulting jobs in which the primary focus was on cutting aluminum. Slivers and burrs were the main problems. To address metal stamping problems such as slivers and burrs, the process engineer, tooling designer, or troubleshooting technician must have a reasonably good understanding of the metal's behavior.

Aluminum Behavior

Aluminum is, indeed, a unique metal to work with. It offers some great advantages and some disadvantages. It is one-third the weight of steel, which gives it a serious advantage in reducing the weight of a part or component. Its great strength-to-weight ratio makes it a candidate for automotive and aircraft industry applications.

It also has some disadvantages: It costs more than steel. Second, it is a very "gummy" or sticky material. It also is very elastic. These mechanical properties can cause stamping problems, especially during cutting or piercing. Aluminum's oxide layer is also very abrasive and can really tear up tool steel.

Not all aluminum behaves the same way. Keep in mind that numerous types of aluminum and aluminum alloys are used in today's stamping industry. Some types, such as the 1000 series, are very ductile, while others can be very hard.

Reducing Slivers

Slivers occur when aluminum interfaces with the cutting sections or punches. To reduce the production of slivers, reduce the severity of friction at the point where the two surfaces interface. The general rule for cutting materials is the softer the metal, the smaller the cutting clearance. This is not always the case, however, especially when you are trying to reduce aluminum slivers.

Because aluminum is relatively soft compared to steel, a great deal of deformation can take place before it is cut. Insufficient clearance during cutting creates compression deformation. Excessive clearance creates tensile deformation (see Figure 1a and 1b).

If the clearance between the punch and the die is too tight, after the metal fractures it decompresses. This decompression causes the metal to grip the punch sides, causing an increase in friction between the cutting punch and the metal. This high friction or rubbing action may produce slivers.

To reduce friction at the interface, increase the clearance between the cutting punch and the die. This stretches the metal into the die slightly before fracture occurs. After the metal fractures, it pulls away from the punch, reducing the friction.

Selecting the correct clearance is a function of numerous factors, including the aluminum type, temper, hardness, cutting angle, and punch geometry. In any case, the cutting clearances should only rarely be below 5 percent of the metal thickness per side. Often simply increasing the cutting clearance to between 12 percent and 18 percent per side can greatly reduce sliver formation.

However, keep in mind that as the cutting clearance increases, so does the burr height. To reduce burr height, make sure that all cutting sections are sharp.

Figure 2 - Although it is desirable to trim steel at 90 degrees to the part surface, aluminum is best-suited for angle cutting; as the angle increases, the cutting clearance decreases.

In short, when you're trying to reduce slivers, make sure that the metal is failing in tension rather than in compression.

Trim at an Angle. Although it is desirable to trim steel at 90 degrees to the part surface, doing so is far less desirable with aluminum. Aluminum is best-suited for angle cutting. Cutting on an angular surface helps to pull the metal downward in tension before cutting takes place, causing the aluminum to pull back away from the punch. As a general rule, as the angle increases, the cutting clearance decreases (see Figure 2).

Sound strange? Remember the goal is to locally strain the metal in tension. By nature, aluminum tends to strain locally, so this just reduces the local area of high strain.

In addition, as the cutting angle increases, so does the need for the cutting sections to be extremely sharp. It is not unusual for a cutting section to have a 0.005-in. radius.

Keep Cutting Sections Square. Make sure that cutting sections are ground perfectly square at a right angle. Even a very slight angle variation can cause slivers. In addition, make sure that the upper section is ground square to the bottom of the section (see Figure 3).

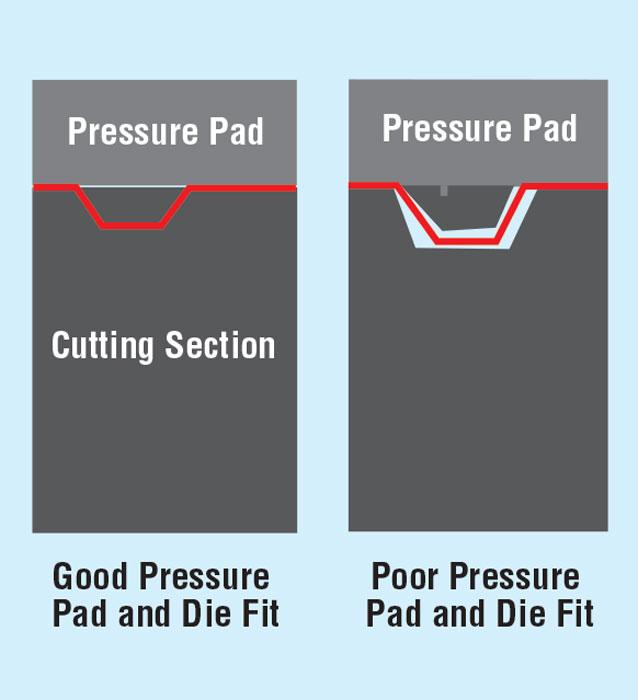

Make sure that the part fits the lower die very precisely and that the pressure/stripper pad closely fits the aluminum part (see Figure 4).

Use an External Pressure Pad. Although using an external pressure pad is sometimes costly and creates scrap removal problems, doing so will most certainly help reduce sliver formation. This helps to pull metal in tension toward the pad, and also helps to refine and reduce the strained area, resulting in fewer slivers and smaller cutting burrs (see Figure 5).

Keep Cutting Sections Finished. The cutting section should have a highly polished surface and should be coated with an antifriction coating whenever possible. Take the time to linearly stone and polish the section in the direction you are cutting. Hand-ground surfaces are extremely poor for cutting aluminum.

Reduce Punch Entry. To reduce the severity of friction at the point where the metal interfaces, reduce the punch entry to as little as possible.

Use Barrier Lubricant. Use a barrier-type lubricant to reduce the friction at the interface.

Completely eliminating slivers in an aluminum cutting operation is a difficult and daunting task. The key is to cause the metal to fail or break in tension rather than compression. This allows the metal to pull away from the punch, reducing sliver formation.

Until next time … Best of luck!

About the Author

Art Hedrick

10855 Simpson Drive West Private

Greenville, MI 48838

616-894-6855

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI