Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Proactive maintenance, predictable performance in metal fabrication

Chicago point-of-purchase fabricator dives into progressive asset management

- By Tim Heston

- January 23, 2015

- Article

- Testing and Measuring

Figure 1

BJ McDonald, whose great-grandfather launched Midland Metal Products in

1921, stands in front of prototype displays, which the company keeps for reference. It

sends polished and painted versions to customers.

A tape measure may seem like the ultimate commodity tool in the fab shop. People spending too much time looking for one could indicate some shop organization is in order. But a tape measure is a tape measure is a tape measure—right?

BJ McDonald doesn’t see it this way. The facilities manager at Chicago-based Midland Metal Products pointed to a tape measure on his desk. It looked ordinary, except for a blue label, an asset tag used for tracking in the company’s computerized maintenance management system (CMMS).

Still, a tape measure has no bearings, no rotating components, and no oil. How on earth do you “maintain” a tape measure?

“I can’t tell you how many times in the old days when we’d look at a tape measure, and the metal component at the end would be bent or some marks would be scrubbed off, and you couldn’t even see the lines,” McDonald said.

Along with calipers and thickness gauges, simple tape measures and rulers serve the same role: They determine whether or not a part is good. “I want to make sure the things that are deciding whether a part is good or not are registered, certified, and verified to be true,” he said, pointing to a station where he periodically checks and calibrates measurement devices traceable to standards published by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

This, he said, is why every asset at Midland receives an asset tag, from large machines to belt grinders to calipers to every ruler and tape measure. The company started its tracking and CMMS initiative to ease attaining ISO certification three years ago. But as McDonald explained, the fabricator’s approach to asset management has had much broader implications.

Midland specializes in the point-of-purchase (POP) industry, a sector notorious for its ups and downs. All the same, the company has experienced dramatic growth over the past three years. Late last year McDonald said he expected sales to reach $18 million, up from $15 million in 2013 and $12 million in 2012.

“I would attribute our lean methodology, our dynamic scheduling, and our number of years in the industry as to why we’re able to gobble up so much market share,” McDonald said.

To implement lean initiatives at this high-product-mix business, Midland needs to have capacity available to meet highly variable demand. Part of this involves ensuring all assets, from the largest automated system to the humble tape measure, are working as they should.

Recession Wake-up Call

Retailers move carefully. Best Buy or Costco may work for months with product-makers to determine how a certain product introduction will roll out. After months of discussion, they finally decide how products will be displayed at the store. So the advertising agency gets to work and calls various fabricators. When reaching out to Midland, the agency talks with sales engineers, who come back not with a PowerPoint presentation, but with an actual display prototype—formed, welded, and painted.

“They ask us, ‘Did you pull this from stock?’ No, we made it just for them.”

McDonald told this story while standing next to a bank of prototypes (see Figure 1). The company sends one prototype to the customer and keeps one for reference, a strategy that has set the shop apart in a competitive niche.

It’s just one niche, though, and it’s one tied intimately to consumer behavior. This led to some serious soul-searching during the Great Recession, when many were wondering whether America’s consumer-based economy would continue as a consumer-based economy. BJ’s parents, co-owners Bernie and Suzanne McDonald, organized a meeting in downtown Chicago with all family shareholders, including BJ and his brother Marc McDonald, business development manager.

The company had grown on the back of the retail business, operating in a small pie-shaped building at the corner of Archer Avenue and Canal Street, with one dog-legged, difficult-to-navigate shipping and receiving dock. In 1986 Midland finally moved to its current 110,000-sq.-ft. plant, complete with receiving and shipping docks on opposite ends of the building. This was back in the days when a retail display had a multiyear life cycle and the shop could churn out hundreds of thousands of the same display, perfect work for the 30 stamping presses Midland used at the time. Then came the rise of China and the wave of offshoring in the early 1990s. As order quantities shrank, Midland replaced its stamping presses with lasers, turret punch presses, and press brakes.

Like so many manufacturing managers in 2009, Midland’s looked inward: Should the company stay focused on only the POP sector? Looking back at the sector’s history, they decided to maintain their focus on retail displays. Their reasoning: Much of the POP business had shifted in favor of manufacturers that respond quickly.

As Suzanne recalled, “Back in the 1970s, displays were designed to last in a certain retail environment for 10 to 15 years, with just a slight change in graphics. This all changed. Retailers need to excite and rejuvenate the consumer, who wants to go into a store and see a fresh look.”

No longer do retail displays have long life cycles. Many don’t have a life cycle at all. Instead, retailers use the display to promote new products for a few months at most. A retail space must constantly change. If shoppers see products displayed the same way for months on end, eventually they stop seeing the products at all.

“An eight- or 10-week delivery is no longer acceptable,” BJ said. “Eight weeks away might be right in the middle of a product promotion.”

The McDonald family launched Midland in 1921, and after working in the POP industry for so many years, they knew that some portions of the sector were countercyclical. During recessions some retailers pull back on TV, billboard, and magazine advertising and focus more on in-store displays. In some respects, the in-store display plays a more valuable role during slow times. People have less to spend, brand loyalty wanes, so advertisements that aim to sustain that brand loyalty have less of an effect. Once shoppers are in the store, though, they may be minutes away from pulling out their wallets, and that’s where the right display can make a difference.

The family decided early on not to lay off any permanent staff and put people to work painting walls and fixing the facility. The slow times also presented opportunity for improvement, rearranging machines to promote smooth material flow. “For years we had identified many of the seven deadly wastes of lean,” BJ said. “We knew we had waste, but the work kept coming in, and when the dust settled, we made a profit.”

For years the family had ensured it had enough cash; the McDonalds had never leveraged out to high heaven, and when they did borrow, they paid the loans off early. Strong financials meant that not only could they keep people on staff, but they could also invest in new equipment. The company today has a new paint line with quick-changeover technology (see sidebar). It has two Cincinnati laser cutting systems with automated material handling. It has a tube cutting laser from AltaMAR, new press brakes with offline programming, and a Panasonic robotic welding cell from Miller with a custom worktable that can be adapted to different jobs.

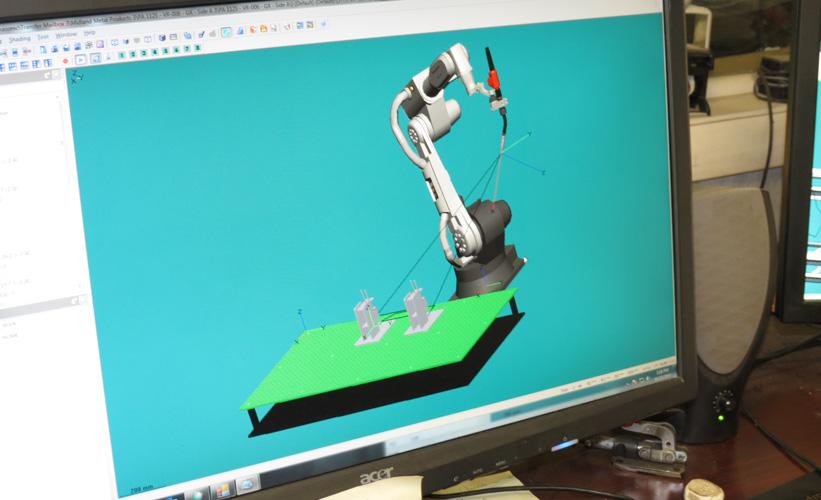

You also won’t find operators programming the robot with a teach pendant. They may use the pendant to touch up and calibrate the program to the actual working space, but for the most part, the shop uses offline weld programming and simulation software (see Figures 2 and 3).

“One of the other keys to success is incorporating the offline, SolidWorks-generated welding fixtures,” BJ said, “which are ‘keyed’ to our own custom Cartesian-coordinated fixture work table, now a permanent component of the machine.”

BJ and his team reorganized the shop to promote better part flow and reduce work-in-process (WIP). All parts for an assembly are cut, formed, and welded at once; there’s no batching. Trace the part flow backward, and you can see work being pulled from powder coating, grinding and finishing, welding, bending, and punching. As operators hang parts on the powder coating line, you can see parts for the same job being offloaded from the punch press.

Ultimately, all these improvements helped the company grow during the upturn, which, as it turned out, occurred much earlier than managers expected. “We prepared like the recession was going to last for years,” BJ said. “But when it didn’t last for years, we found ourselves in a much better spot.”

The Little Things

New software and machine technology play roles in reducing response times, as do shop organization and layout. But compressed lead times leave little room for error.

BJ knows this all too well. He walks to the southeast corner of the plant into his office—or as he calls it, “command central.” He looks at two wide-screen monitors that by default show real-time views of the operation coming from 2 dozen webcams stationed at the loading and receiving docks and at various manufacturing processes in between. All this helps BJ react to any unforeseen problem.

Ideally, though, problems shouldn’t be unforeseen but instead predicted and prevented—hence the shop’s CMMS from Bigfoot and all those blue asset tags. BJ has entered all those assets into the CMMS, which tracks usage and sends reminders for preventive maintenance (PM). For measuring devices like tape measures and calipers, PM includes a calibration traceable to a NIST standard (see Figures 4-6).

“When I’m being audited for ISO, and they ask for our NIST-traceable documents, I don’t have to go diving into a file cabinet,” BJ said. “I just sit in my office with the auditor, and I fulfill every single attribute of his inspection by looking at this screen. I’m tracking 220 items that refer to weights and measures alone—every tape measure, caliper, thickness gauge; everything is tracked.”

He uses the CMMS to track conventional equipment, too, of course, and he’s found that since implementing the system three years ago, corrective or reactive maintenance has plummeted to near zero. These days most maintenance activity at Midland is preventive.

Figure 4

Midland places asset tags on everything, from its largest machines and grinding stations to brooms.

According to BJ, using a CMMS has helped the shop catch problems with small, inexpensive assets, like hand tools, that normally wouldn’t throw up a red flag. But problems with these small assets still can prolong overall manufacturing time. The little things really make a difference.

For instance, every month BJ uses the CMMS to produce a snapshot analysis of all the recorded downtime for the previous month. The report shows asset downtime regardless of whether or not the problem slowed production. A worker may be able to access a backup tool to keep jobs moving, but what if all backup tools are in use?

“Even if it’s only a small hand tool that’s broken, and even if I have another one I can give the person, I still label it [in the CMMS] as ‘downtime.’ I’m not reporting favorably. I’m reporting worst-case scenario.”

BJ continued with a recent example: “I pulled up the screen and saw this small air riveter had 33 hours of downtime. This thing kept needing to be repaired, and we didn’t have the parts in stock. All the hours of downtime were in fact worth more than the value of the thing.” So he simply replaced the tool.

The CMMS periodically sends work orders to employee inboxes, stating that they need to take certain tools to BJ’s office for inspection and calibration. Tools are lasting longer. No longer do people just throw a caliper in a toolbox when they’re finished. That caliper has an asset tag on it, and it’s assigned to them in the CMMS, so they’re taking better care of it.

Assets Ready for Quick Response

Because the company started tracking its assets only three years ago, it has yet to build a long history of downtime for most of its larger machines. Moving forward, BJ said the company will use the system to plan new equipment purchases.

He also said that, from a broader perspective, tracking assets has added a layer of predictability in a highly variable fabrication business with customers who demand quick response. Like at any job shop, Midland’s product mix changes continually, and a certain asset may not be needed all the time. But if an asset isn’t available for production, it can’t spring into action when needed, and it certainly can’t help the fabricator make money.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Hypertherm Associates implements Rapyuta Robotics AMRs in warehouse

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI