Technical Manager

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Improving flying cutoff operations, mill productivity

Cutoff management strategy gets most from the blades and the mill

- By Daniel Johns

- December 16, 2014

- Article

- Tube and Pipe Production

Editor’s Note: This article is adapted from “Cutoff management to improve uptime and profitability,” presented by Daniel Johns at Pipe & Tube Houston 2014, sponsored by the Tube & Pipe Association International® and the International Tube Association, Houston, Sept. 16-18, 2014.

Making tube or pipe is anything but easy. During a typical shift, the mill operator has to keep an eye on a dozen variables and make scores of decisions to keep the mill running at maximum productivity. Most of the focus is on big-picture items like line speed and weld heat to make sure the line is running as fast as possible and inline inspection results to verify that the mill is making salable product. However, many details come into play too. How are the bearings holding up? Are the rolls still in good condition? Is the scarf bin filling up again? How long has it been since I changed the scarfing tool? Why is the cutoff saw making that noise?

Consumables near the end of the line, specifically the scarfing tool and the cutoff blades, aren’t high-profile items and therefore don’t usually get a lot of attention. However, no mill can run without them, so from that standpoint, they are just as important as every other component on the mill. In fact, a good cutoff management program can have a big impact on the mill’s productivity.

Getting the Most Service Life From Each Blade

Compared to the substantial capital investments involving a tube mill and peripheral equipment, a saw blade’s cost is insignificant at best. But as a consumable item that gets replaced several times per shift, it deserves enough attention to maximize its usefulness.

Foremost is cut depth. A blade that penetrates the workpiece’s ID just a couple thousandths of an inch, say 0.220 in., stays engaged in the wall and delivers a smooth cut. A blade that goes to a depth past the tooth depth loses contact with the wall. The result often is a step in the tube’s or pipe’s end face. This is a drawback downstream if the customer needs a smooth end face.

A much bigger and immediate problem is that a blade that cuts deeper is more likely to contact the ID scarf, which is much harder than the parent material. This can cut the blade’s service life by 75 percent.

The mill itself provides other information about the state of the saw blades. A knowledgeable mill operator can use these clues as diagnostic indicators to resolve small problems to maximize blade life.

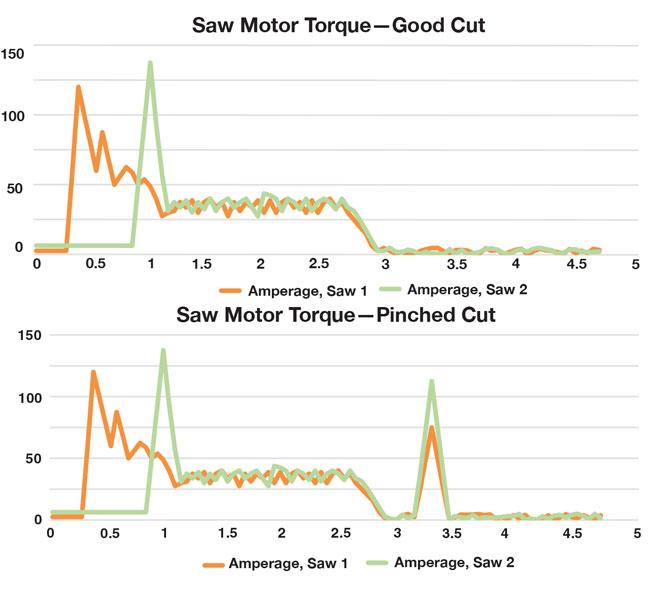

Saw Torque. One of the simplest diagnostic tools is the saw motor’s ammeter. It measures the current drawn by the saw’s motor, which varies according to how much torque the saw develops. When everything is running normally, the saw develops essentially no torque until the blade makes contact with the tube. The current increases rapidly as the blade cuts through the tube wall, then settles down for the duration of the cut. It takes little more than a glance to see if the saw is cutting normally (see Figure 1).

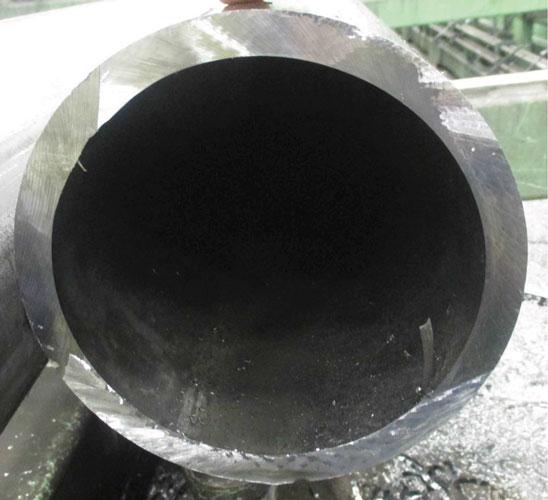

More Visual Clues. The end face of a cut tube also provides information about cutting conditions. A tube end with a consistent appearance and minimal burr is the result of a satisfactory cut. A rough area toward the bottom of the tube is an indication of a misalignment on the mill. See Figure 2.

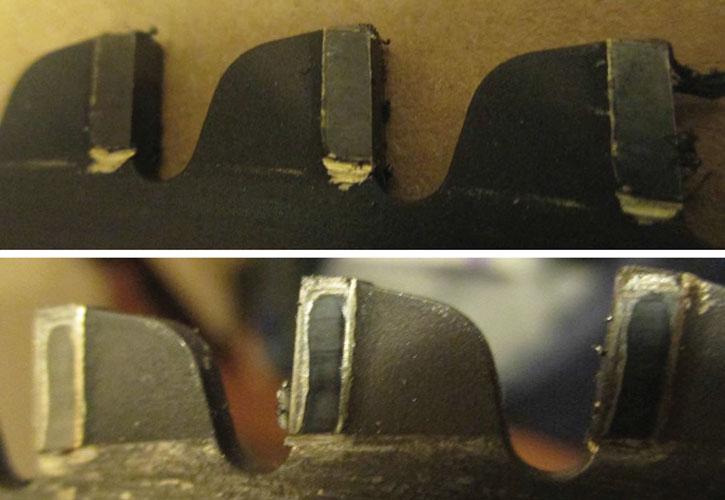

Uneven wear on the saw teeth is a third clue of a cutting problem (see Figure 3).

Figure 1

A saw’s ammeter tells a story. The two blades of an orbital system enter the material at different times, causing two distinct spikes in the current draw; after that, the cut proceeds normally (top). A current spike near the end of the cut means that the tube pinches the saw blade when the cut is nearly finished, indicating a mill alignment problem (bottom). This is detrimental to the service life of the saw blade.

Getting the Most Productivity From the Mill

For any piece of capital equipment, maximizing productivity is a matter of minimizing downtime. It’s easier said than done, but cutoff management can be an important part of maximizing the productivity of a tube or pipe mill. Cutoff management—the strategic control of processes in and around the cutoff to produce the highest-quality product while achieving maximum mill uptime—doesn’t have to be difficult or complicated, but it does require some time to do a bit of research.

The efficiency of the cutoff management program is based on how the company chooses, uses, and changes the saw blades in its cutoff system. Of these three practices, how it changes the saw blades probably has the biggest overall impact on the company’s profitability.

Changing a cutoff blade, or a pair of cutoff blades, isn’t a big ordeal. It typically takes less than 10 minutes. However, that time adds up. Consider the number of changes and total number of hours of downtime per year for the various types of cutoff saws (cutting medium-wall mild steel):

- Single blade, up to 4 in.—600 changes (85 hours)

- SOrbital, up to 4 in.—500 changes (57 hours)

- S Twin blade, 4 to 7 in.—350 changes (45 hours)

- S Orbital, 4 to 7 in.—600 changes (85 hours)

- SOrbital, 7 to 12 in.—800 changes (113 hours)

- SOrbital, 10 to 16 in.—1,200 changes (170 hours)

When to Change. In a best-case scenario, every saw blade would be near the end of its service life when the mill was due for a scheduled shutdown, product changeover, or other sort of downtime unrelated to the cutoff. In other words, changing blades would have no impact on the mill’s uptime.

A worst-case scenario is something else altogether. Imagine a mill operator focused on squeezing every bit of capability from every saw blade, running each one until it’s too dull to cut effectively, and shutting the mill down for the sole purpose of replacing it. How much productivity would be lost for each blade change?

To determine that, it’s necessary to know the material and the line speed. For a tubular product that measures 4.5 in. OD by 0.250-in. wall thickness, running at 150 feet per minute (FPM), the downtime costs 8.5 tons of productivity per blade change. For a larger, heavier-wall product, the losses are greater. For example:

- 9.625 in. OD by 0.435-in. wall thickness, 120 FPM: 25.6 tons per blade change

- 16 in. OD by 0.495-in. wall thickness, 100 FPM: 41 tons per blade change

Of course, nobody runs a mill like that, but replacing a blade while it still has plenty of life left is the exception rather than the rule. It’s not uncommon for 70 percent of cutoff blade changes to cause mill downtime.

Reversing that ratio, so that only 30 percent of the blade changes cause downtime, is a matter of planning, using most of the scheduled shutdowns to change the blades.

In a hypothetical scenario, a mill makes 4.5-in. product, 0.250-in. wall thickness, at 150 FPM, producing 0.84 ton of tube every minute. The cutoff blades are durable enough to cut 1.5 sq. meters of material before their performance starts to degrade, so any blade change before the blade has cut this much material doesn’t cause downtime; any blade change at this point or later does cause an 8-minute shutdown.

In Case 1, the operator tries to get the most life possible out of the saw blades; 70 percent of the blade changes cause downtime, for an annual loss of 48,280 tons of production. In Case 2, just 30 percent of the blade changes cause downtime, for an annual production loss of 20,400 tons (see Figure 4). Switching strategies to go from Case 1 to Case 2, which is the result of some planning—and awareness that 8 minutes of downtime has much more value than a saw blade—adds 27,800 tons of output per year.

Figure 2

When a tube mill and its cutoff saw are working together in unison, the tube end shows a consistency from contact with the saw blade. An inconsistency (bottom 20 percent or so) shows that this tube was pinching the blade as the cut was nearing completion.

A Plan With Teeth

Ingrained habits and work practices take time to change. In some cases, the change is a hassle. Asking a tube mill operator to replace the cutoff saw blades during scheduled downtimes is a matter of adding one more thing to his already lengthy to-do list. It’s going to take more than a pep talk or memo from the supervisor.

This is where key performance indicators (KPI) come into play. If you’re not using KPIs, or if you’re using saw blade life as a KPI, it’s time to change that, putting the focus on mill uptime. Even this might not be enough. To really get the mill operators’ attention, a reward for maximizing mill uptime is probably in order. The motivation doesn’t need to be costly or complex. Frequent payout of a small yet meaningful bonus, proportional to the mill’s uptime excluding events beyond his control, would be a good incentive.

About the Author

Daniel Johns

4931 26th Ave.

Rockford, IL 61109

800-435-7297

About the Publication

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Zekelman Industries to invest $120 million in Arkansas expansion

3D laser tube cutting system available in 3, 4, or 5 kW

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

HGG Profiling Equipment names area sales manager

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI