- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

An upgrade can be a game-changer

- By Nick Martin

- September 18, 2014

A lot of people tend to say that you need to be able to use the tools on hand to get the job done. I also agree with this, but sometimes you just can’t. From a job shop perspective, sometimes the worker is only as good as his tools. Every shop has its limits, and it is important to know them. When you see that limit being pushed, you will see a need to decrease the amount of time spent on jobs and increase your quality and output. That usually means that it is time for an upgrade.

Your co-workers or employees definitely appreciate a nice tool or machine. If it makes their job easier, they are happy. The boss man also smiles when he sees parts hit the floor faster than they did before the upgrade.

One machine that comes to mind when I think of this is our press brake. When I was fresh out of college and helping in the shop, I often helped bend some parts on our Roto-Die® press brake. I was pretty gun-shy about using this machine because it looked very prehistoric. Hence the name “dinosaur” for old machines in shops like ours.

The Roto-Die was a dull green machine, and it was the first thing you noticed when you walked into the shop. It was accompanied by two large wooden “layout tables” that often were a breeding ground for trash and extra parts. I remember the previous owner, Wade Barnes, who worked for my dad, coming to the tables, grabbing a piece of metal or tubing, and then pushing it across the table to clean it off. I also vividly remember several obscenities coming from his mouth.

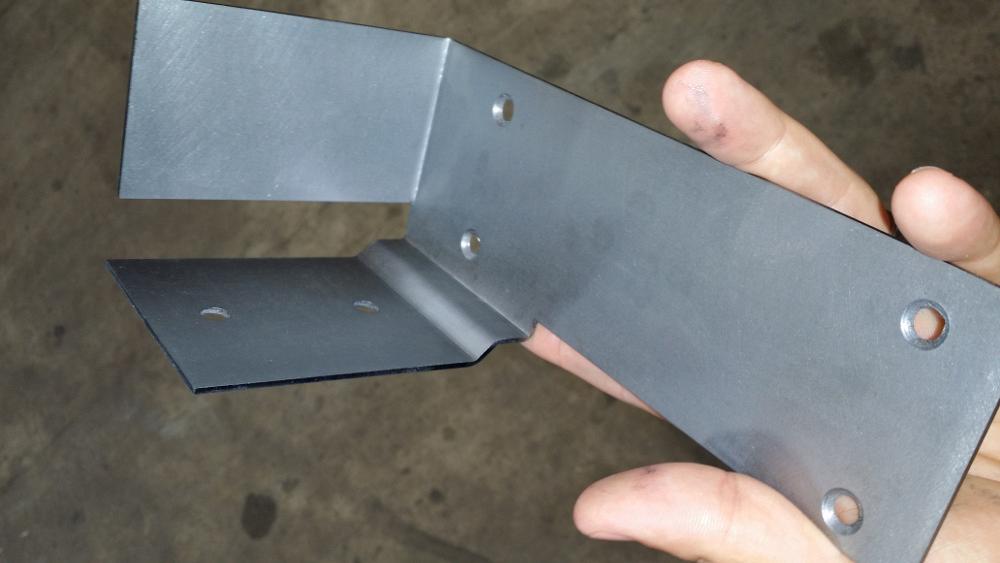

Always on the tables were several squares, hammers, prick punches, shears, and scribes. My coworkers would use these tools to lay out parts that came off the shear or the old plasma burn table. I remember holding the flat pattern in the press brake while the operator called out commands on how to brake the part. They were often “Show the dot,” “Hide the dot,” “Split the dot.” I was just doing as I was told at the time and trying to learn what I was actually doing. I was just as green as the press brake.

Tool changes were not the quickest or the easiest. One tool could take up the entire 10 feet. We didn’t have segmented tooling; that was considered a “slot” that was cut in the tool at different locations for braking pans.

If production was in order for repeatable parts, we set up a makeshift backgauge. This was often a large piece of angle or multiple pieces of angle held in place by C-clamps. When setting up the backgauge, we used a stop to hold the ram into place while we set the clamps. This stop was a small metal block with a long rod on it. We basically shoved it in behind the foot pedal so the ram would not return to the up position. The stroke tonnage was the same every time, but the gap or how far the ram came down was adjusted by a dial located at the top of the ram. It often took several tries to achieve the correct bend angle, and the part had to be checked after every five to 10 parts. Production parts with several different flanges had to be staged, requiring a lot of lay-down room. I remember folding parts all day, and it felt like I was constantly handling the same exact part.

I didn’t have a lot of knowledge of the fabrication world when I first started, so I was always in learning mode. My dad mentioned that we were getting a new press brake, a definite upgrade, and it would change the way we currently did things. I was very excited about that and knew that this would be a great opportunity to learn.

Press brakes have come a long way in the last 10 years and they are constantly getting more advanced. More options are helping brakes spit out faster than a mom’s right-arm chop at a stoplight. You can get all sorts of bells and whistles on these machines. Your budget may not have you checking so many options on the sales order, but you can still get a solid machine from several different manufacturers. Dad chose a Cincinnati Proform 175-ton press brake with an automatic backgauge, auto-crowning, and a touchscreen monitor with a pretty straightforward program. At the time I had no clue what the options meant and, especially, how they would change the shop.

We got this blue monster brake on a truck, and the first thing I noticed was the touchscreen computer monitor. With my computer background, I thought this was pretty sweet. I remember parts of my brain starting to click as I trained on the machine. The software was laid out into different mechanical sections of the machine, and I began to relate to what the heck I had been doing on the Roto-Die. I picked up the software side pretty quick, but the knowledge of when and how to brake parts up still left something to be desired. You can learn how to run the brake in a day or two, but the know-how of braking parts can take several years.

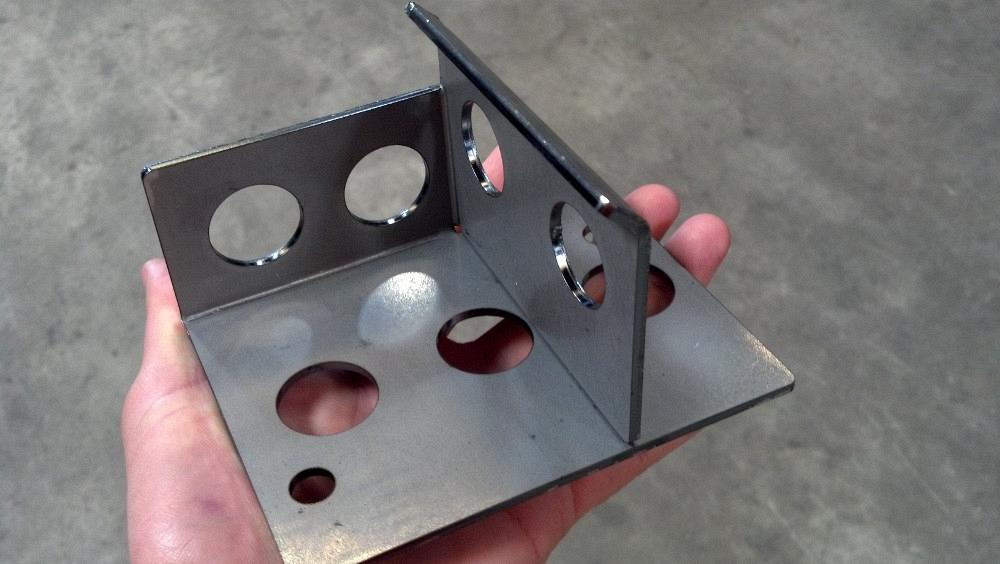

A 14-GA mild steel part with four brakes and four countersunk holes.

Photo courtesy of BarnesMetalcrafters.

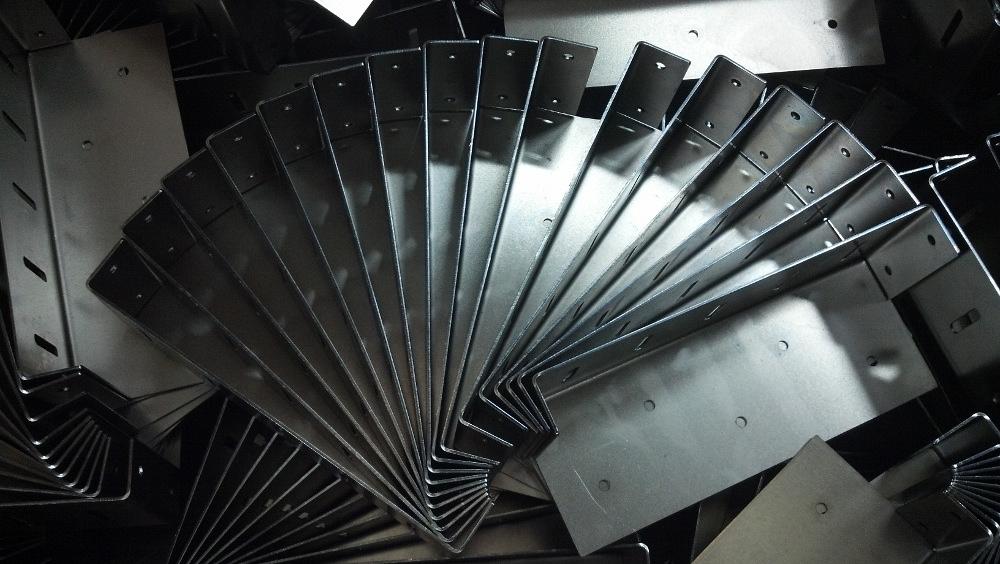

The tooling was segmented and easy to change out for different radius callouts and part lengths. Production parts were easily programmed, and the files were saved for later use. The layout tables were becoming a thing of the past. I was seeing the shop modernize right in front of me. Those tables were replaced by carts that made their way around the shop, flowing from one process to the next. Correct angles were achieved quickly and could be adjusted with a simple touch of the computer monitor. Repeatability was trusted and reliable, requiring angle checking less often.

I distinctly remember doing a production run with my niece Ashley, who worked during the summers. We were braking up pans that had 12 steps, and we were knocking them out. My dad came up to the machine and watched us for a bit. He just stood there and kept chuckling with a huge smile on his face. Two people with little knowledge of manufacturing were replacing a few days’ worth of work with one easy-paced day.

Although our Roto-Die was a workhorse in its day, the new brake was opening new doors on what we were capable of doing. Our limits increased and are continuing to rise with knowledge of the machine.

I may be preaching to the choir here, but to me, this was all new. For the first time, I saw and felt a change in how things were done in the shop. An upgrade can be a real game-changer for a small shop like ours. I now could see parts come to life right in front of me. I was no longer intimidated, like I was with the dinosaur. There were no dots to call out; I could drive the pedal and make the machine dance. Parts were hitting the floor.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscriptionAbout the Author

Nick Martin

2121 Industrial Park Drive SE

Wilson, NC, 27893

252-291-0925

- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI