- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Medical device manufacturing and the need to adapt

- By Vicki Bell

- November 9, 2016

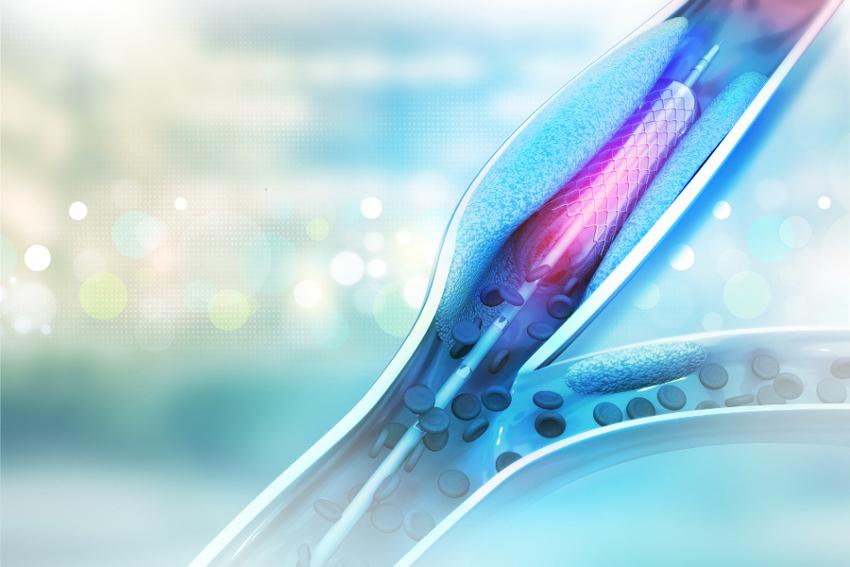

My husband died October 8. Luckily, he was administered CPR by some good Samaritans as soon as he went into cardiac arrest. With their quick, efficient actions, he survived a massive heart attack to make it to the hospital, where a stent was placed in his 99-percent blocked artery. He’s doing OK, now, thanks to some amazing people and a stent that was implanted in his artery by a highly skilled physician.

We are grateful to the many people who came to his aid, and we also are grateful for the stent and countless other medical devices fabricated and used every day to improve and even save lives. Chances are you, or someone you know is the proud owner of such a device.

A stent is a small mesh tube that's used to treat narrow or weak arteries—blood vessels that carry blood away from your heart to other parts of your body.

According to information on The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH) website, stents usually are made of metal mesh, but sometimes they're made of fabric. Fabric stents, also called stent grafts, are used in larger arteries.

My husband received neither a traditional metallic nor a fabric stent. His is a bioresorbable stent approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration just this year.

Manufactured by Abbott, Abbott Park, Ill., The Abbott Absorb stent is made of a naturally dissolving material, similar to dissolving sutures. It disappears completely in approximately three years, after it has done its job of keeping a clogged artery open. By contrast, metal stents are permanent implants that restrict vessel motion for the life of the person treated. No metal also means the treated artery can pulse and flex naturally as demands on the heart change with everyday activities.

We are hopeful that this stent will perform as intended and create no serious side effects.

Upon learning about the stent, the thought crossed my mind that metal manufacturers had been accustomed to making metallic stents, which first were available in 1988. What issues did they face moving from metal to the bioresorbable material? Were metallic stent manufacturers able to transition easily to working with a different substance? What changes in processes and equipment, if any, were required?

These are questions I’ll be asking the next fabricator I encounter. I’ll have many opportunities to ask them next week at FABTECH® in Las Vegas. My husband will be there, and seeing him will remind me to ask.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscriptionAbout the Author

Vicki Bell

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8209

- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI