Owner, Brown Dog Welding

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Preserving history

- By Josh Welton

- January 14, 2016

2016 opened with me, you guessed it, on the road. The “day job” sent me to the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland to do some secret squirrel work. APG is actually the Army’s oldest active proving ground; it’ll hit 100 years in operation next year. It’s my first trip to the ground, and I’m digging it.

I haven’t spent much time on the East Coast, so with a little downtime I decided to take advantage of the opportunity and visited both the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Va.

Charles Lindbergh’s autobiography, The Spirit of St. Louis, was one of the books I couldn’t put down last year. It was part of the required reading list friend Sam Smith put together for me in my quest to become a better writer. Lindbergh’s personal account, not just of the first solo trans-Atlantic flight from New York to Paris, but of the preparation and the life events that led to that flight, spoke to my soul and stirred up a new sense of adventure.

Walk into the National Air and Space Museum and look up. The Ryan Airlines-built single-seat monoplane, the purpose-built Ryan NYP, or as most of us know it, The Spirit of St. Louis, hangs suspended from the framework of the building’s ceiling. Just to be that close to something I’d recently invested so much imagination in was a unique sensation … you know it really happened, but breathing the same air as the plane and reading the plaque “Gift of Charles A. Lindbergh” created a grip that won’t let me go. That flight happened, and along with Lindbergh’s genius and tenacity, it led to so much that happens in the sky above us right now that we take for granted.

In an upstairs display, only steps away from the suspended Spirit of St. Louis, sat the Wright Flyer, Orville and Wilbur’s heavier-than-air machine that first put man in the sky. Crazy side note: While developing the plane, Wilbur wrote for and received any aeronautical research the Smithsonian Institution had. Full circle.

The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Mich., has a replica of the Flyer, and having an annual pass to the museum, I’ve seen it many times. The feeling, however, of standing a foot away from the original is, again, gripping. Perhaps one day I’ll be able to more accurately describe it, but for now, it is the closest thing we have to time travel.

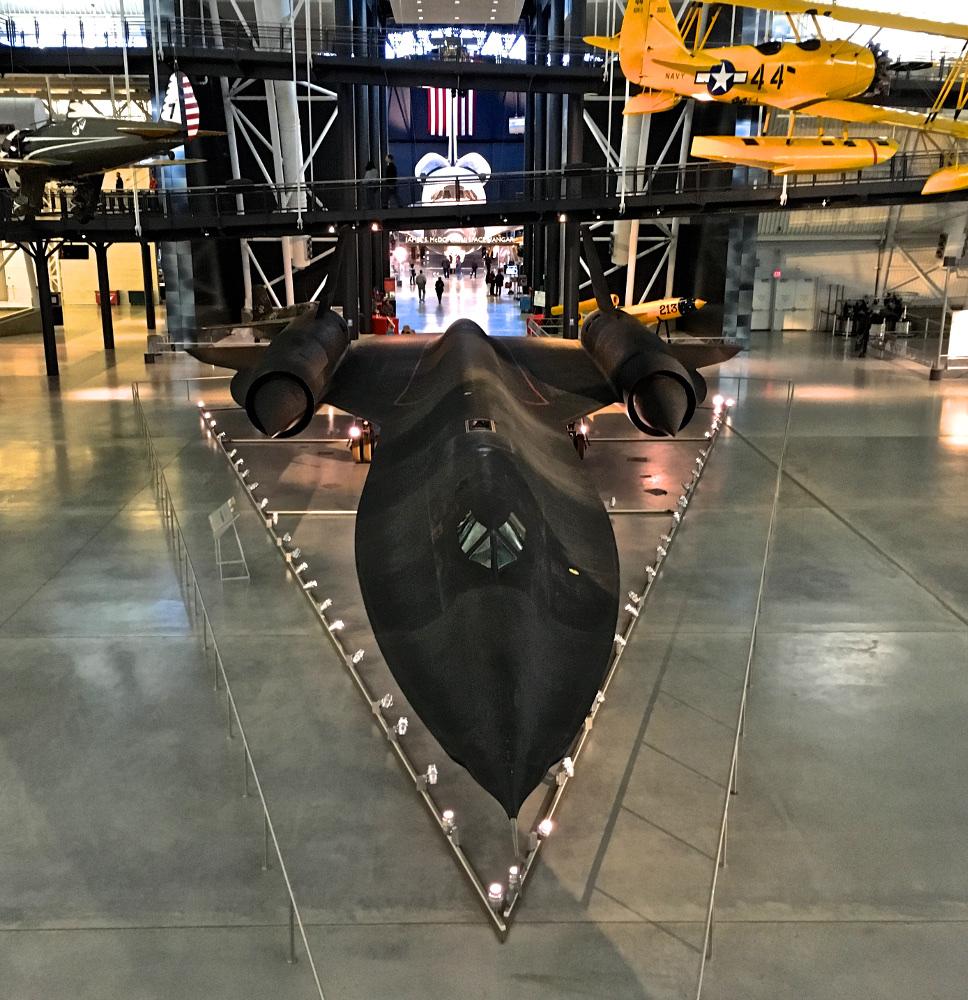

The Udvar-Hazy Center is an extension of the National Air and Space Museum. It comprises several hangars housing, duh, air and space travel artifacts and a large restoration area.

The rock star at center stage is the SR-71 Blackbird. It’s a machine more believable as myth than history, and yet there it sits seemingly fresh from its LA to DC flight in which it averaged 2,124 miles per hour. This is an aircraft that simply outran enemy missiles. Think a “Star Wars” starship’s hyperdrive, except real life. It was also more than a handful to wrangle, as 12 of the 32 Blackbirds built wrecked, none due to enemy fire.

From the entrance, to the left of the SR-71, sitting on massive stanchions, is a Boeing B-29 Superfortress. Not just any B-29 Superfortress, though, this is the Enola Gay. The bomber that dropped the bomb. Little Boy, Hiroshima. The fact that the aircraft is restored and displayed is even controversial. For periods of time it sat and rotted. Then shown to the public in pieces. Now rebuilt and exhibited. Originally picked by Col. Paul Tibbets Jr. to be his bomber while it was still on the assembly line—and named for his mother who encouraged him to fly. “The Great Artiste” and “Necessary Evil” were two of the other bombers in the Japanese missions. “What is in a name,” as Shakespeare would ponder.

As I stared at the glass enclosed cockpit, at eye level, my mind could only try to go to the place that the pilot and his crew were in. Soldiers doing their duty. An unprecedented weapon. So many killed. So many saved?

For my money, the coolest corner of Udvar-Hazy is the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar. From the second floor you can look through glass to watch restorations in process. Museum workers are spread throughout the space, concentrating on a number of ongoing builds. A weld shop, sheet metal shop, and machine shop are visible along the edges, and I felt a tinge of jealousy while observing the craftsmen concentrating on their precious tasks.

It would be my desire that you all experience these pieces of American, world, and human history firsthand. I’ve hit on but a fraction of the immense collection of aircraft the Smithsonian holds, a couple of crafts and displays that speak to me. Go find those that speak to you.

All images courtesy of Brown Dog Welding.

subscribe now

The Welder, formerly known as Practical Welding Today, is a showcase of the real people who make the products we use and work with every day. This magazine has served the welding community in North America well for more than 20 years.

start your free subscriptionAbout the Author

About the Publication

- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Sheffield Forgemasters makes global leap in welding technology

Welding student from Utah to represent the U.S. at WorldSkills 2024

Lincoln Electric announces executive appointments

Engine-driven welding machines include integrated air compressors

ESAB unveils Texas facility renovation

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI