Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Our Publications

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

A 3D printer is a ‘hardware store in a box’ for fab shops

3D printers let fabricators build everything from standard hardware items to custom form tools

- By Don Nelson

- November 4, 2019

- Article

- Additive Manufacturing

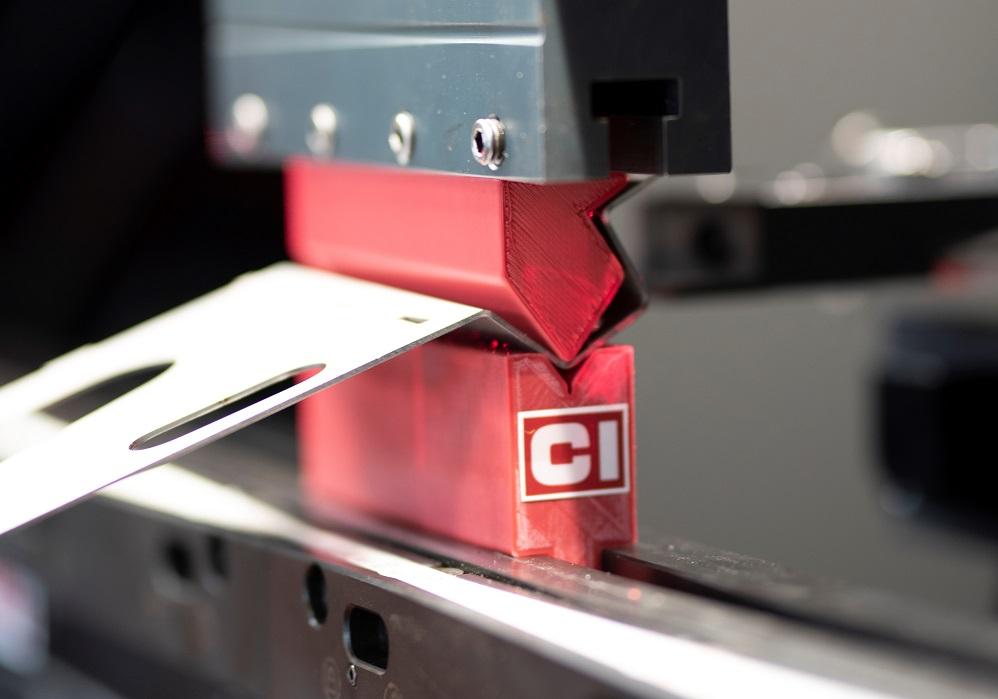

This special press brake tool was 3D-printed from PLA. The tool made approximately 1,000 hits, and the material cost $20. Cincinnati

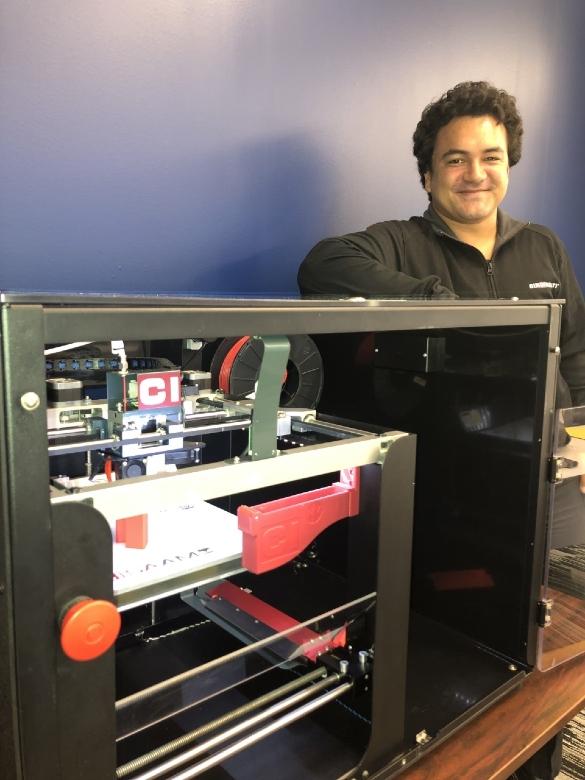

Access to a 3D printer is like having a “hardware store in a box,” said Cincinnati Inc. Senior Product Specialist Mark Watson during a seminar titled “3D Printing for Fabricators,” held at the headquarters of FMA Int’l, publisher of The Additive Report®.

A polymer-parts printer can build everything from snaps, clamps, and wrenches to storage containers and organizers to jigs to the plastic feet that hold a prototype aloft. “Just all kinds of things that a fabricator uses,” Watson said during a post-seminar interview, adding that many designs for such shop aids can be downloaded as STL files for free at Thingiverse.

He also identified gauges, check fixtures, and forming tools (WATCH VIDEO) as being especially good devices for fab shops to 3D-print.

Custom Gauges

Gauging is critical to the success of any bending operation, especially when working with tight tolerances or workpieces with irregular shapes. And sometimes a part is impossible to gauge, even when the press features a sophisticated multiaxis backgauge system.

A standard press brake can gauge off many different surfaces of a part. “But problems can arise when the operator has to gauge from a contoured surface,” Watson said. “Most press brakes cannot gauge from a contoured surface well.”

A 3D printer allows a shop to build a custom gauge that precisely conforms to a contour. Designing and printing a polymer gauge might take just a few hours, saving significant time and money compared to CNC machining.

It also lets a shop produce parts without seeking approval for a design change from the customer.

Consider the critical dimension of a part being formed on a press brake. For the part to work properly, said Watson, the dimension must be held to a tight tolerance. “And let’s say you have to gauge against a horrible surface. That’s the worst. You might have to punch holes in the part—called pilot holes—and then you would pin-gauge to those holes. If you don’t have a 3D printer with the ability to make custom gauging fingers, you would have to go through the process of asking the customer if it is OK to change the part for the pin-gauging process, because if you punch a hole … you might destroy the part.”

Speedier Inspections

Additively manufacturing devices for inspection tasks also can save shops time and money.

A machined check fixture can take a week or longer to produce and cost $500 or more, which compares unfavorably to two days and $20 to $100 for many 3D-printed fixtures. One Minnesota fabricator cut the time needed to make a gauge by 65 percent and shaved 40 percent off its cost by 3D-printing it.

Similarly, it’s easy and economical to print check fixtures for every member of a family of parts, as well as the inspection tools needed for small volumes of parts.

A downside to 3D-printed polymer inspection devices is that they wear faster than metal ones. This can lead to tolerance drift, requiring plastic check fixtures to be replaced more frequently. It’s worth noting that newer nylons and other advanced thermoplastics have greater wear-resistance than earlier materials. But, as with most decisions in manufacturing, choosing to use or not use a 3D-printed check fixture will depend on the specific application.

Watson cited one company he works with that has put a lot of effort into improving and streamlining its press brake operations. And the payoffs have been significant. “No joking around,” said Watson, “they can change over their machines—going from last good part to first new good part—in five minutes. On a press brake, that is very good.”

Quality control and documentation have proven to be efficiency blockers, however. Part inspection takes 15 minutes, meaning it takes longer to measure and document a part than to set up the press to produce it. Remedying that problem is one of the company’s goals.

According to Watson, using a 3D printer to build go/no-go fixtures that check angles, flanges, inside radii, and material thickness would help the company achieve its QC goal.

Tooling Time?

Among the biggest time and cost savings additive manufacturing provides is it allows fab shops to 3D-print thermoplastic press brake tooling. (Note: Plastic tooling should only be used for air bending applications.) Before acceptance of such tooling percolates throughout industry, though, fabricators will need to accept that plastic tools can bend metal.

Fabricators who see polymer tools form metal for the first time are “shocked and amazed,” said the general manager of Cincinnati’s Additive Manufacturing Division, Chris Haid, who also spoke at the FMA seminar. “They say, ‘Plastic is weaker than metal. How can that work?’”

Some shop personnel are “five years ahead of their time” with respect to adopting polymer tooling, added Haid, who, along with several colleagues at MIT, invented a 3D printer and launched a company that Cincinnati acquired in 2017. “But for the most part, it’s an area where you have folks that are slower to adopt this stuff.”

He sees that changing, though, and expects fab shops to evolve considerably in the next few years. “You will see a lot more 3D printing done in shops.”

Watson said one of his customers, a fabrication shop near Chicago, has already embraced the advantages thermoplastic tooling offers. Among its specialties is forming the metal point-of-purchase displays found near grocery store checkout lanes.

To win a job, the shop and its competitors present their concepts to the advertising agency that designed the display. Competitors typically bring paper drawings or 3D-computer renderings of the display, while Watson’s customer presents a full-scale metal prototype formed with 3D-printed plastic tooling.

“They have advertising agencies asking, ‘How do you do this? How did you make a prototype so quickly?’” Watson said. “It’s all because of plastic tooling.”

Among the advantages of this approach, he said, is that the customer isn’t unveiling a drawing but a to-scale model of the display. “First of all, it looks beautiful,” Watson said, adding that it’s not unusual for an agency to tell his customer, “‘If you can make the next hundred like that, you got the job.’ Well, surely, they can make it. They already have.”

About the Author

Don Nelson

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

(815)-227-8248

About the Publication

Related Companies

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI