- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Defibrillators—Should you have one in your workplace?

- By Vicki Bell

- May 29, 2003

- Article

- Safety

|

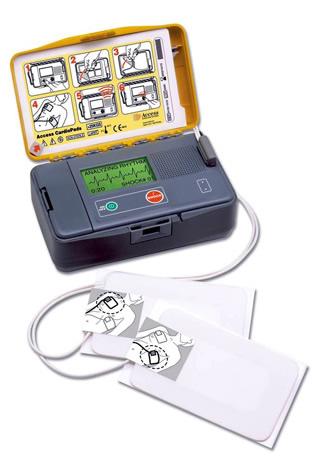

| Photo courtesy of American Heart Science. |

In December 2001 the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) released a statement encouraging employers to consider making automated external defibrillators (AEDs) available in their workplaces. This announcement followed the November 2000 Cardiac Arrest Survival Act (CASA), a law that called for placing AEDs in federal buildings. AEDs are an important lifesaving technology and may have a role to play in treating workplace cardiac arrest.

At the time of its announcement, OSHA stated that 13 percent of workplace fatalities reported during the previous two years were due to cardiac arrests. Most cardiac arrests are caused by an abnormal heart rhythm, usually ventricular fibrillation (VF), in which the heartbeat quivers or flutters rather than pumps. The only treatment for VF is electrical defibrillation—shocking the heartbeat into a regular rhythm.

According to the American Heart Association (AHA), AEDs are important because they strengthen the chain of survival. When a person has a cardiac arrest, his or her chances of survival decrease by 7 to 10 percent for each minute that passes without defibrillation.

How AEDs Work

Unlike the manual defibrillators that have been used in clinical and emergency medical services (EMS) for nearly 50 years, AEDs, which were introduced in 1979, contain built-in computers that evaluate the victim's heart rhythm and judge whether defibrillation is needed. Some AEDs then prompt the user to deliver a shock. Fully automatic defibrillators deliver a shock without prompting the user to press a shock button. The current is delivered through the victim's chest wall through adhesive electrode pads.

Are AEDs Safe to Use?

The AHA stated that an AED is safe to use by anyone who's been trained to operate it. Studies have shown that the devices accurately detect a rhythm that should be defibrillated 90 percent of the time and when not to shock 99 percent of the time. AEDs are designed with multiple safeguards and warnings and are programmed to deliver a shock only when VF has been detected.

|

| Photo courtesy of the American Heart Association. |

However, potential dangers are associated with AED use. Untrained users may not know when to use an AED, and they may not use the device safely, exposing themselves and others to electric shock.

It's possible to be shocked or to shock bystanders if water is standing near or underneath the victim. The victim should be moved to a dry area and any wet clothing removed. The victim's skin must be dry or the electrode pads won't adhere to the skin. At no time should anyone touch the victim while the shock is being administered.

AEDs should not be used on a child younger than 8 years old or weighing less than 55 lbs.

The Importance of Training

The AHA, the Red Cross, the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM), and OSHA are among the many organizations that strongly recommend training for laypersons who might be called on to use AEDs—both in the use of AEDs and in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). The AHA offers the Heartsaver AED course and the Red Cross offers an adult CPR/AED course.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), along with the AHA, is conducting a study to determine if it is realistic and cost-effective to train large numbers of people to use AEDs. The study is scheduled to be completed in 2003.

The Legalities

Many businesses are reluctant to implement an AED program, fearing the possibility of lawsuit. A 2001 information sheet from the AHA stated, "There have been no known lawsuits against lay rescuers providing CPR as Good Samaritans, nor any against AED users. However, the perceived potential for a suit against a lay rescuer using an AED has in some cases been a deterrent for companies or organizations considering establishing an [AED] program."

If you want to research the laws in your state, visit www.csg.orgto see a listing of state Web sites. Also, your state's EMS department (usually part of the state Health Department) can provide information.

The AHA also recommends consulting your company's legal advisors and taking the following information into consideration:

Cardiac arrest victims essentially are already dead. They lose consciousness, have no pulse, and stop breathing in a matter of only a few moments. Most often the heart's rhythmic contractions become ineffective, chaotic spasms so the heart can't pump blood to the brain or the rest of the body. The only thing that can change this condition is defibrillation. Using an AED can only help, not harm.

Modern AEDs are safe and easy to use.

The accuracy of an AED is greater than that of a trained emergency medical professional.

To sue an AED user or purchaser successfully, four essential elements must be proven—duty, breach of duty, causation of injury, and legally recognized damages.

Training targeted rescuers in CPR and AED use provides the knowledge to use both safely. AHA's Heartsaver AED course also instructs how to minimize risks to the user and victim in unusual cases, such as when the victim is lying in a pool of water, has an implanted defibrillator, or is on a metal surface.

Most AED manufacturers offer some type of insurance to purchasers of their devices.

|

| Photo courtesy of American Heart Science. |

The AHA also sees a changing trend. As awareness of the new generation of AEDs grows, companies and organizations may face greater threat of liability if they aren't properly prepared to respond in a timely manner to a cardiac emergency. Three lawsuits filed against companies that weren't prepared substantiate the changing trend. In 1996 Busch Gardens® was found negligent for not being prepared and not having a defibrillator to respond to a 13-year-old guest.

Lufthansa Airlines also was found negligent because it failed to provide appropriate treatment to a passenger who suffered a cardiac arrest. United Airlines faced a similar suit.

Setting up Your AED Program

If you've weighed the pros and cons of having an AED on-site and have decided to provide one in your workplace, how do you proceed? The ACOEM recommends that employer-sponsored programs include all of the following elements:

1. A centralized management system for the program– It is important that clear lines of responsibility be established for the program and that roles are defined for those who oversee and monitor the program.

2. Medical direction and control of the program– It is recommended that all workplace AED programs be under the direction and control of an appropriately qualified physician. Specific areas in which medical direction is important include providing the written authorization required in most locations to acquire an AED, ensuring provisions are made for appropriate initial and continued AED training, and performing a case-by-case review each time an AED is used at the site. Additional responsibilities would include establishing or integrating the AED program with a quality control system, compliance with regulatory requirements, and ensuring proper interface with EMS.

It also is recommended that administrative coordination of the program be provided by a licensed health care professional or an appropriately qualified health or safety professional responsible for workplace emergency programs. The administrative coordinator in consultation with the program medical director for issues of medical control should supervise the day-to-day management of the program.

3. Awareness of and compliance with federal and state regulations– This includes regulations requiring that every person expected to use an AED be properly trained in both CPR and AED use. Skills should be reviewed and conducted at least annually, preferably semiannually.

4. A written AED program for each location– It is recommended that each of the 12 elements stated in this guideline be incorporated in the written document to be posted at each location.

5. Coordination with local emergency medical services– Required by many state regulations, information about each workplace AED program should be communicated to EMS providers and coordinated with EMS response protocols.

6. Integration with an overall emergency response plan for the work site– It is recommended that the AED program be a component of a more general medical emergency response plan, rather than a freestanding program. The medical emergency response plan should describe in sufficient detail the continuum of personnel, equipment, information, and site activities associated with managing the range of anticipated occupational injuries and illnesses for a patient who is not breathing or in cardiac arrest. All employees should be notified of the plan, including the proper means for notifying trained internal and community emergency responders.

The part of the plan covering the AED component should contain the following:

- a. Notification of workplace medical personnel and first aid responders during all operating times of the site

- b. Assessment of the situation by the first trained responders at the scene

- c. Notification to the community EMS system

- d. Appropriate first aid, including body substance isolation procedures and use of CPR and AEDs by first aid responders if indicated

- e. Clinically appropriate patient transport from workplace to medical facility, including how appropriate continuation of care will be ensured

- f. Responder debriefing and equipment replacement

- g. Methods to review the follow-up care received by the patient

7. Selection and technical consideration of AEDs– It is recommended that selection of AED equipment be based on the most current recommendations of the AHA available in Guidelines 2000 for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. These guidelines state that compared to higher-energy escalating (200 joules, 300 J, 360 J) monophasic-waveform defibrillators, relative low-energy (200 J) biphasic-waveform defibrillation devices have been shown to be safe and of equivalent or higher efficacy for termination of VF. If a higher-energy escalating monophasic defibrillator has been acquired previously, it may be used as long as training of responders adequately addresses particular aspects of such devices.

8. Ancillary medical equipment and supplies for the workplace AED program– Besides the AED, other medical equipment and supplies are required to support the safe, complete management of cardiac emergencies, including:

- a. Bloodborne pathogens responder and cleanup kits

- b. CPR barrier masks with oxygen port

- c. AED responder kits to support electrode pad connections. (Items include a razor to shave chest hair and a towel to dry sweat from the chest or after removal of a nitroglycerine transdermal patch.)

- d. Appropriate portable emergence oxygen equipment

- e. A CPR audio prompting device to guide action and timing sequences of CPR ventilation and compressions

9. Assessment of the proper number and placement of AEDs and supplies– It is recommended that placement be no more than 5 minutes away from possible sites of cardiac arrest.

10. Scheduled maintenance and replacement of AED and ancillary equipment– The manufacturer's recommended service schedules should be followed or exceeded, and records of all servicing, testing, and replacement testing should be kept.

11. An AED quality assurance program– The QA program should contain at least the following components: a medical review of each use of the AED; recordkeeping of all training, AED locations, service, updates, and medical reviews; and a program evaluation to assess the efficacy of the program and a system to remediate or improve components as necessary.

12. Periodic review and modification of the program protocols.

The complete ACOEM guidelines can be found at https://www.acoem.com/guidelines/article.asp—ID=41.

Properly implemented, an AED integrated with your medical emergency response plan can be a true lifesaver.

About the Author

Vicki Bell

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8209

About the Publication

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI