Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Building community with lean manufacturing

Allis Roller revitalizes improvement effort

- By Tim Heston

- February 6, 2019

- Article

- Shop Management

In one of the company’s manufacturing cells, an operator runs a chopper product through a balancing operation.

Read through The FABRICATOR archives between 2009 and 2013 and you’ll find all sorts of stories about companies in dire straits that made dramatic changes. Most of them being custom fabricators, the shops cherry-picked from various improvement methods, including lean manufacturing, the theory of constraints, and quick-response manufacturing.

Each story follows a common theme: The boat was sinking, and everyone worked together to plug the holes. Why did they make the effort? Because they had no choice. The Great Recession spurred great changes.

But change can be a tough sell when times aren’t particularly difficult. Company leaders see cracks in the system and problems down the road, but there’s no emergency. And the work environment isn’t riddled with dysfunction. In fact, the manufacturer does so many things right already. Why fix what’s not broken?

This is Allis Roller’s challenge, and it’s now making strides to overcome it.

A Growing Company

Based in Franklin, Wis., Allis Roller fabricates steel and rubber rollers used for agricultural equipment like combines and balers, as well as products for heavy machines in transportation, mining, and general industrial applications. The company’s 80-plus employees make a variety of other products too, including shafts, quick-disconnect products for hydraulic machinery, and a “long tail” of custom parts.

The manufacturer uses both machining and various fabrication processes. On the factory floor you’ll see the welding of steels and alloys using various wire, subarc, and gas tungsten arc processes.

Like most manufacturers in the U.S., Allis Roller isn’t a one-trick pony. It’s a dynamic place with forward-thinking leaders. David Dull, president and CEO, also serves as chair of the Franklin Business Park Consortium, a collection of 14 local businesses, most of them manufacturers, that together employ about 2,500 people. Working with area community colleges, the companies pool resources to pay for (among other things) training classes on lean manufacturing, supervision, machinery setup, and blueprint reading.

Beyond this, many Allis Roller employees interact with high schoolers every day. The company participates in a program called GPS Education Partners. “We have close to 30 students, juniors and seniors from local high schools, come here every day,” Dull said. “They take classes in our classrooms here, and then they spend time working at various local companies. Some work here [at Allis Roller], while others work at companies in the business park consortium.

“We know we need to develop our own workers, make them more valuable to help us be more productive. We also promote a skilled trades program in the community. All this helps us create a culture where people want to learn. This helps us compete in a job market with less than 3 percent unemployment and a Foxconn plant, going up 20 minutes away, that will be hiring thousands of people.”

Dull arrived at Allis Roller in 2009, a tough time for the company and many other manufacturers. Between 2007 and 2009 commodity prices skyrocketed, and Allis Roller found that it couldn’t pass all those price increases on to many of its customers.All this, Dull said, put pressure on the company to be more efficient. The company hired a lean consultant and launched some projects, including a few multiprocess cells dedicated to certain products with predictable demand. Then the economy improved and order volume ramped up from major customers. Business improved steadily from 2011 on, and in the middle of that growth—in 2014—the company moved to a new, 110,000- square-foot building, almost tripling its available manufacturing space. The new space happened to have a few big classrooms, and Allis Roller has kept them rather than repurpose them. Company leaders figured that, moving forward, spaces for education will be just as important as spaces for office or factory work.

On top of this, the company has launched a joint venture in Brazil that will be contributing to the manufacturer’s overall annual growth rate. Dull expects the annual growth rate to be between 10 and 15 percent during the next three years.

In other words, things are looking good, and employees are busier than ever, but Dull and his leadership team see cracks in the façade. Productivity and on-time delivery performance for certain products could be improved, and the company relies on a homegrown, manual scheduling technique.

“We have a scheduling tool that revolves around a couple of people here who manage everything from what’s moving through the shop floor to contracted outside services like heat treating and painting,” said Russ Dudan, vice president of operations. “It’s functioning right now, but we’ve about reached the limit. We intend to grow this business, and the foundation we have isn’t going to support that growth … [That said,] I am really impressed with where the company is and am excited about positioning the business for future growth.”

Empathy, Ergonomics, and Adding Value

John Gil, continuous improvement engineer, started at Allis Roller in the middle of 2018. He saw a progressive company that had invested in cross training, which is critical in any improvement initiative, and especially critical for Allis Roller’s high-product-mix environment.

He also saw several existing cells, including one devoted to a product called a chopper, which, on agricultural equipment, chops hay and other material. But he also saw a factory that could benefit from other tools in the lean toolbox, including 5S, standard work, total productive maintenance, and single-piece part flow.Gil, who speaks fluent Spanish, saw more opportunities for improved communication with the factory’s Hispanic population, with the use of visual aids and visual management. Over the past months he has observed workers and helped build consensus for change—essentially through empathy by putting himself in the worker’s shoes and involving them in improvement efforts, even for something as basic as taking out the trash. Too often trash and recycle bins either were hardly full or were overflowing. Workers carried out trash when they had a free moment, but as busy as they were, those moments didn’t happen often enough.

Of course, carrying the bins out was a chore, so as Gil implemented a trash carry-out schedule, he also “made sure that every container has a dolly attached to it. So now operators can roll two bins at a time, instead of making two trips.”

With more observation came more ideas for improvement. Gil observed that the shop tended to slow down during the last 10 minutes of a shift. “The last 10 minutes of the day weren’t very productive to begin with, because people were winding down from a busy day,” Gil said. “So we put that time to use, and going forward they now spend the last 10 minutes of every day organizing and cleaning up their workstations and surrounding areas. This not only helps keep the production floor clean and orderly, but it also helps the sustainment effort.”From Push to Pull

These actions may seem like small steps, Gil said, but they’re really building the foundation for further improvements down the road, some of which might look like what’s going on at the company’s manufacturing cells.

Allis Roller President and CEO David Dull (left) joined the company in 2009, while Russ Dudan, vice president of operations (center), and John Gil, continuous improvement engineer, joined the company in 2018.

These include two cells dedicated to product families for two specific customers, one in the ag equipment business and the other in mining. The cells each have different manufacturing processes grouped together, including milling, pressing, turning, welding, straightening, assembly, balancing, and packaging.

A typical tube flowing through the cells is 8 in. diameter with a 0.25-in. wall thickness. Balancing and straightening are critical operations. The final spec on total indicated runout (TIR) is less than 0.013 in.

Physics sometimes stands in the way of maintaining an efficient cycle time. For instance, welded parts in these cells need about 10 minutes to cool before they’re placed on a balancing machine (similar to balancing the wheels on a car). Historically, workers simply added a small work-in-process (WIP) inventory buffer to accommodate, removing one part from the weld fixture and placing it on a cooling rack.

In recent months, though, workers have been able to eliminate excess handling by adding a second balancing station and by introducing air lines to cool the product faster. Now they no longer need to move parts to and from a cooling rack. Instead, they pull a workpiece from welding and take it directly to one of the balancing stations. During cooling, the worker moves to another station to balance a separate roller. Once that product is balanced, the other roller is cooled, so the worker can start that balancing operation immediately.

Another improvement in the works for these cells is shifting from push to pull production. Today work is scheduled and “pushed” into the cells, similar to how work is scheduled for other departments and work centers throughout the plant. Putting disparate processes together in the cell has shortened transportation time, but the push scheduling still tends to build WIP, especially as estimates vary from actual processing times.In the near future Gil said the cell team plans to introduce signals, such as andon lights, at downstream assembly processes within the cells. These will effectively “pull” parts from upstream processes and, ultimately, govern the rate of order releases. The pull process will also govern the utilization of resources, as cross-trained workers move where needed (such as to balancing or assembly) to free a temporary bottleneck and to ensure a constraint operation (the welding process in this case) is never starved of work. After all, an operation is only as productive as its slowest process.

That tenet of Eliyahu Goldratt’s theory of constraints is one point company leaders continue to drive home. You’re only as strong as your weakest link. A machine may have off-the-charts uptime metrics, but if a constraint (be it welding or anything else) is starved of parts, all that machine uptime won’t make the operation produce more.

To be competitive and gain market share, the company needs to produce more with the same resources—and this is starting to happen, especially within Allis Roller’s cellular operations. Eventually improvements will free up capacity that Dull and his team can sell to companies demanding similar products.

At this point lean manufacturing has made serious headway in Allis Roller’s high-volume products with predictable demand, but there’s much more to do. Besides scheduling (which may undergo some changes as the company implements a new enterprise resource planning system), the “long tail” of custom and low-volume products awaits. For now that segment of the business remains in a traditional, process-centric layout, though managers now are researching (and debating about) improvement tools that show potential. On the immediate horizon, though, is a more pressing concern: building the cultural foundation for continuous improvement.

Buying Into Lean

Getting worker buy-in on the “what”—the nuts and bolts of changes on the floor and in the office—is relatively straightforward. For instance, Gil approaches every problem with not only efficiency but also safety and ergonomics in mind. Less handling makes a worker’s day safer and easier. Even simple dollies on trash cans can make a world of difference.

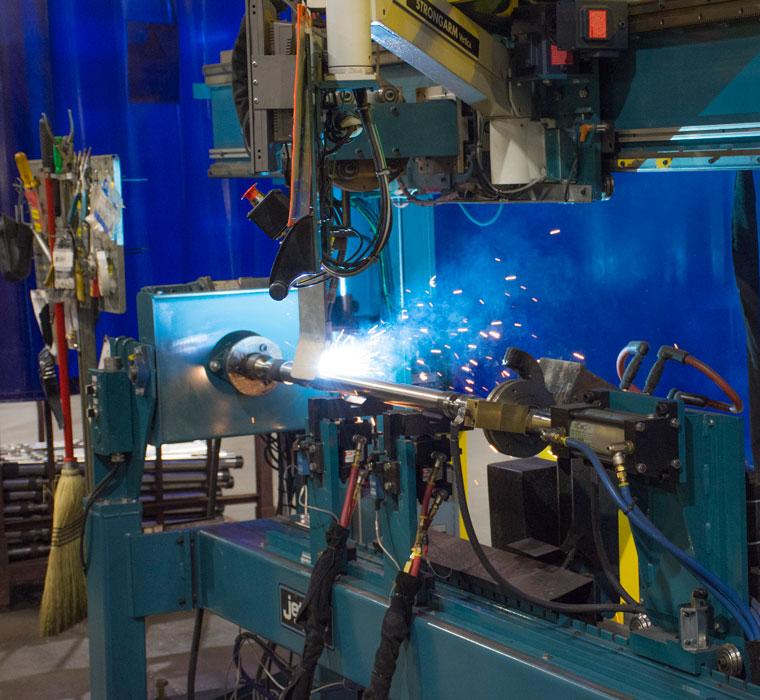

An operator sets up a robotic welding job. This robot cell produces a variety of parts, including some that flow through one of the company’s multiprocess cells.

The “why” behind lean is a less concrete concept, but as sources explained, it’s critical to convey if employees are expected to take ownership and truly sustain improvement. It’s one reason the “why” was the focus of an all-employee meeting in late December, when a PowerPoint slide Dull showed effectively conveyed the point. It didn’t give efficiency or financial metrics, or describe the importance of quick response, shorter lead times, and greater profits.

Instead, the slide showed a photo of one of the company’s products being used. It’s a critical component in a customer’s product. The customer and, by extension, the people at the customer’s factory depend on that product. They need it to do their jobs, to feed their families, and, again by extension, build their communities. A good weld, a new fixturing idea, a better handling method: these little ideas and more can make a real difference in the wider world.

Photos courtesy of Allis Roller, www.allis-roller.com.

Franklin Business Park Consortium, franklinbusinessparkconsortium.com

GPS Education Partners, gpsed.org

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI