Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Fabricator tackles the focus and flow of continuous improvement

New kinds of jobs helps sustain the effort

- By Tim Heston

- October 9, 2018

- Article

- Shop Management

When Brookville, Pa.-based Miller Fabrication Solutions hires a new employee, many of the company’s 350-plus workers know it. They see new employees walk the floor, learn all about safety, personal protective equipment—the standard (and very important) stuff. But they also learn about gemba walks, looking for muda (waste), and the company’s overall approach to lean manufacturing.

Anyone who has been around metal fabrication might notice something odd about Miller’s shop floor. Things look calm and not particularly busy. Work is neatly labeled and contained within designated areas. The whole place looks, well, let’s be honest, a little boring. But most who work there wouldn’t say it’s boring, just controlled and professional. They know the plan, and they know what to work on next.

“We’re a different company now than we were five years ago.”

So said Rich Steel, director of business processes, adding that he was referring to more than just the company’s new name. Up until last month Miller Fabrication Solutions was known as Miller Welding & Machine Co., a name that came from its origins refurbishing and fabricating machines and equipment for the local steel industry.

“The big name change illustrates our capabilities,” said Susan Towers, marketing director. “We’ve obviously grown quite a bit since our founding 55 years ago.”

Five years ago the company had already transformed significantly, and the changes were documented in the November 2014 edition of this magazine. (For more, visit www.thefabricator.com and type “Piecing together the continuous improvement puzzle” in the search bar.) But improvement never stops, and over the past few years the shop has implemented some novel ideas, most of which relate to two areas: flow and focus.

The Value of Lean

About eight years ago as the economic recovery picked up steam, Miller had doubled its size in just a few years. And the shop looked so busy—operators walked swiftly with paper travelers in their hands, asking supervisor questions, looking for material, running huge batches of it, and working overtime to get it all done.

In a way, the Great Recession’s effect on the industry was Miller’s saving grace, as Eric Miller, company president, recalled in a 2014 interview. “Coming out of the bad years, the industry shifted. Quality and delivery were the key focus for customers, and we struggled. We had always been regarded as high performers in quality, and we were still considered that, but we weren’t even close to hitting our customers’ goals.”

Customers raised the bar, and Miller had to rise to meet it. To do so, managers rethought what a busy shop floor should look like. When the company’s lean efforts began in earnest, managers focused first on flow. They began with the fundamentals, including 5S and limiting batch sizes, corralling work-in-process (WIP) to taped areas on the floor. They realized that the more WIP the shop had, the longer it took for the job to flow from the first operation to the shipping dock. After the improvements, any employee, even on his or her first day, could look at tape on the floor and various signage and know where parts were coming from upstream and where they were going downstream.

Workstations were organized, some machines were moved into cells, products were reorganized into product families, and takt times were developed. Because these cells produced a variety of products, takt times were based on average processing times. Nonetheless, the takt gave employees a sense of where they were in the flow—behind, ahead, or on track.

Optimal flow could only get the company so far; it also needed to change its focus. Thanks to the fabricator’s customer mix, with its strong presence in the construction mining, and oil and gas industries, Miller had to deal with large swings in demand.

Rather than rely solely on overtime and temporary workers, managers turned to the concepts behind sales and operational planning and refined their capacity planning. They worked with core customers, developed forecasts, and produced certain products ahead of the busy season to help level-load the operation. This broadened the focus beyond the next job and got people thinking about available capacity weeks and months ahead of time.

Maintaining the Flow

Miller now is well more than five years into its lean initiative, and the scrutiny of flow continues unabated. That scrutiny starts with inventory. Increased finished goods could be strategic—for example, to serve as a buffer to ship enough products during periods of peak demand. The same could be said of raw stock inventory, especially during these days of rising material prices. If a fabricator finds a deal, it makes business sense to spot buy a little extra material.

But what about the WIP between manufacturing steps? That, Steel said, is scrutinized continually. He pointed to one cell that had an excessive number of kits of parts between a welding robot and a machining center. Why were there so many kits?

It turned out to be a cycle time imbalance. Picture a cell in which two parts are fed into a robot. The parts emerge and then are sent to a manual welding operation, complete with spreader bars to mitigate distortion effects. Those spreader bars were the first clue of something amiss. That particular weld sequence required significant cooling time. As it turned out, that lengthy weld sequence was performed after previous welding operations but before weld cleanup and machining.

As Steel explained, “They always had two or three kits worth of parts between final welding and machining, because that WIP gave them that time buffer to allow the parts to cool. And that buffer was never really controlled. It could be two kits, it could be four kits, it could be more. So we ended up reversing two stations [within the cell]. This meant that the two parts that required the most time to cool were welded first.”

As those parts cooled, other parts were being welded. Then, after the final welding step, the kits would move forward together through weld cleanup and machining—no extra WIP and time buffer required.

The company also changed the cell’s production method. Today it’s no longer producing to a dispatch list, with the intent to hit a daily quantity. Instead, a rolling cart controls capacity. Employees call it a rolling kanban cart, and it’s operated following the logical rules of replenishment. An empty cart triggers replenishment; a full cart indicates that the cell can’t handle more work, so, when possible, employees move downstream to clear the bottleneck.

“No longer are kitting [personnel] held to a dispatch and hitting daily targets,” Steel said. “They now produce kits [of parts] whenever they get an empty cart.”

Put another way, production personnel are not held to certain production targets but instead focus on throughput. Who cares if a welding robot products umpteen parts a day if, thanks to a constraint elsewhere, only a portion of those parts can be placed into a kit and sent downstream to the next operation?

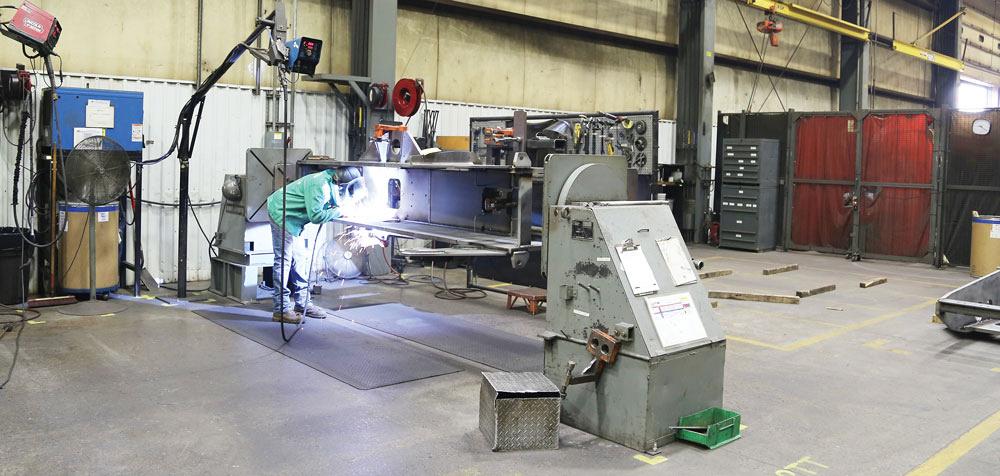

An employee welds a large workpiece mounted on a rotating positioner. Tools are organized, and the area is free of WIP.

These small changes, both in sequence and kanban replenishment, increased throughput and reduced WIP from 14 kits to six. The new sequence and replenishment arrangement also allow people to be more productive. To keep up with customer demand, that cell needs to produce seven kits a day. It used to take seven employees to produce that much, and now it takes only four.

“We have available capacity in that cell in machining and robotic welding, but we choose not to utilize that capacity,” Rich said, “and we could actually push it up to 14 kits a day, because we understand what we can do within that line.”

The team at Miller attained the flow—reserving certain resources to ensure they’re always available to meet highly variable demand—that gives the operation the broad focus. It’s no longer about the next job, about squeezing more out of this laser cutting center or that press brake. It’s about how to make the best use of resources to meet customer demand over weeks, months, and years.

Who Owns the Process?

Even though it’s years into a lean manufacturing initiative, Miller still has trouble sustaining certain initiatives.

Steel recalled a 5S initiative for prototyping and first-article operation. “At first they were skeptical, but by the end of the three-day kaizen event, they were all onboard and were excited about their new work areas.” To sustain the 5S, Miller performs a biweekly audit, a 20-question survey in which auditors rank work area 5S from 0 to 5, with 5 being the best.

“I don’t spend a lot of time in and around the prototyping area,” Steel said. “And after about a few months, their scores began to backslide. It ended up being a coaching moment.” Management didn’t want them to drop everything and spend hours maintaining 5S. “We’re just looking for five or 10 minutes, so that they can at least sustain [the 5S] they have.”

The challenge with sustaining any lean initiative is that the “what” gets in the way of the “how.” Employees focus on what they need to accomplish to meet production goals, but how they accomplish it—the process—doesn’t receive the same attention.

For years Miller has contracted with lean consultant (and columnist for this magazine) Jeff Sipes, president of Back2Basics LLC. Through conversations with him, company leaders realized that a company’s structure can make sustaining lean even more difficult. A production manager or supervisor invariably gives more weight to what needs to get done: Jobs need to be produced on time at levels that exceed quality requirements. These managers focus on satisfying customer demands, and rightly so.

Thing is, this narrow focus creates a problem. Bending over backward to produce parts for a specific customer may wreak scheduling havoc on other orders. Employees do take ownership of the process and develop daily improvement ideas. But besides the continuous improvement manager, no one focuses solely on the quality of the process.

Several years ago, Miller experimented with a new structure as it launched a total productive maintenance (TPM) program. Maintenance personnel always had reported directly to production managers in the facility where they worked—which made perfect sense. After all, their job is to keep machines available and running to meet customer demand. In this sense, the maintenance technicians and the supervisors they reported to focused on the desired results: machine uptime.

Workpieces are staged for machining. Tape on the floor limits WIP. Every item, including every workpiece and tool, has its place.

If a machine broke down continually, maintenance technicians would review the metrics, scrutinize the maintenance schedule, and perhaps alter maintenance practices to prevent those breakdowns. Still, this by nature is reactive, not preventive. Could the TPM program be structured in such a way that someone would always have an eye on not what needed to be maintained or fixed, but how the maintenance was done? Put another way, could someone “own” the maintenance process?

Miller now has restructured its maintenance to make room for such a process owner. Maintenance technicians still report to production, but alongside them, a maintenance process owner focuses on the process of maintenance.

With someone always having an eye on how things are done, maintenance can prevent any procedural issues before they snowball into a larger problem. That process owner doesn’t report to production but directly to the continuous improvement manager. In Miller’s case, that’s Steel. His title used to be lean development manager; it’s now business process manager.

Since introducing the process-owner concept in maintenance, Miller has implemented a similar concept in the quality department. Until recently, quality technicians reported to the quality manager. That’s not unusual, but it also led to some inefficiencies. “If we needed quality support on the nightshift or on weekends, we needed to have conversations, get approvals, and communicate with the quality manager as to why something needed to happen,” Steel said.

Under the new structure, quality technicians report to production managers. This gives production management complete freedom in scheduling and resource planning. The quality manager is now the quality process owner. He no longer manages what needs to be done, which again is under the purview of production management, but instead focuses on how quality is measured, what procedures quality technicians follow, the technology they use, and how the quality team could be more efficient.

“This change was made earlier this year,” Steel said, “and we’re now considering this same idea for our engineering, automation, and process development groups.”

Managing the What and the How

Company leaders hope this new structure will help the company sustain its lean initiatives. Various lean experts often tout the power of ideas from front-line employees. Teach machine operators and welders the basics of lean, and they may well give their own ideas for improvement.

As Steel and others at Miller have found, this works well during the early days of a lean initiative. But once those first ideas are scrutinized, developed, and acted upon, what then? Employees are taught to look for waste—and as Steel describes, it’s now part of the fabricator’s new-employee orientation. Still, employees also need to get jobs out the door.

Process owners, however, do not focus on the immediate need to ship a job, but instead on how jobs flow. They focus not on the what but on the how—and that ultimately is what continuous improvement is all about.

Miller Fabrication Solutions, www.millerfabricationsolutions.com

Back2Basics LLC, www.back2basics-lean.com

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI