Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

In custom metal fabrication, time means everything

K-zell Metals doesn’t sell fabricated products, it sells time

- By Tim Heston

- June 6, 2018

- Article

- Shop Management

In early March K-zell Metals gave a shop tour to about 50 people during The FABRICATOR’s Leadership Summit, part of the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association Annual Meeting.

Attendees of the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association’s Annual Meeting stepped off a bus, enjoying the brisk, clean air of an early March morning in Phoenix. They had come to tour

K-zell Metals, a custom fabricator with 35 employees.

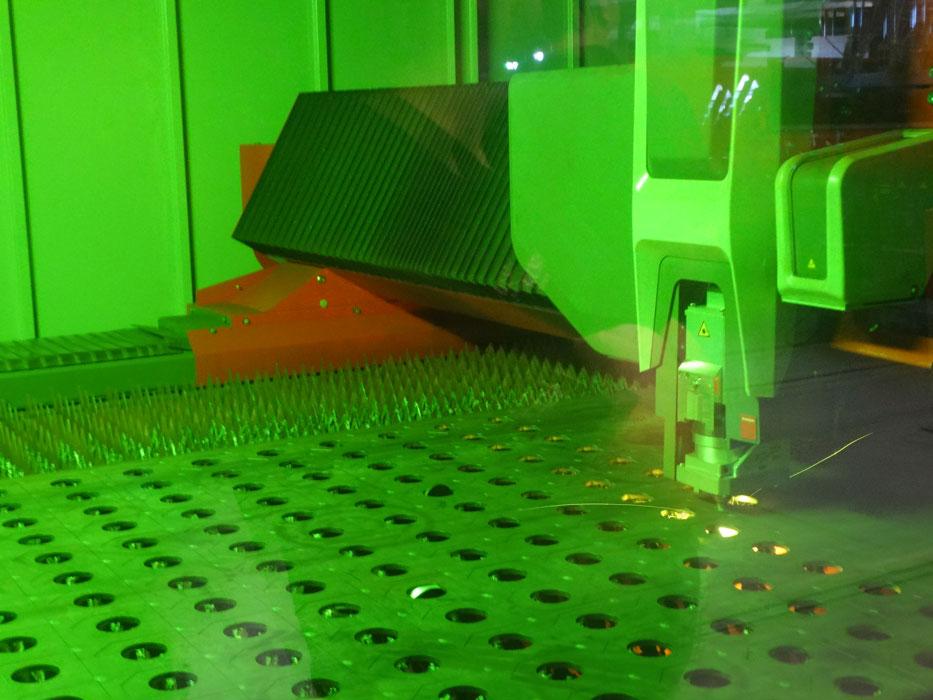

The shop looked typical enough, with the usual cadre of equipment: lasers, press brakes, welding cells. For sure, attendees could tell ownership continued to reinvest in the business. An automated 10-kW Bystronic fiber laser, installed in December 2017, was proof enough of that. Many attendees came from some progressive shops themselves. The new equipment—the robotic welding cells, modern Bystronic press brakes with touchscreen controls, the CO2 flat sheet laser with a fixture so it could cut angle as well as square and rectangular tube—all looked familiar and probably refreshing.

At the start of the tour, when K-zell President Don Kammerzell spoke, you can feel a sense of camaraderie in the air. Here was someone like them, an owner who cares, who reinvests, who respects his employees, and who thinks about the long-term success of their shop.

Soon Kammerzell spoke of metrics, a tenet of excellence in custom metal fabrication, and an absolute necessity for an ISO 9001-certified shop like K-zell Metals. “I really don’t care whether we ship on time.”

Wait. What? Selling Time

Kammerzell clarified that the company does deliver most jobs on time and is considered one of the most reliable sheet metal job shops in the Phoenix market. All the same, to understand his comment, it helps to understand where Kammerzell is coming from. Before launching K-zell in 1986, he made a living as a metallurgical engineer, and in many respects he still thinks like one. He analyzes what matters, and he knows certain metrics can be misleading.

Consider the adage “If you don’t measure it, you can’t improve it.” That’s true, but a shop first needs to define what it needs to improve. If a fabricator focuses solely on on-time delivery and improves it by extending lead times when possible, hiring people, buying equipment, and increasing inventory, the company might soon find itself in an unsustainable, money-losing situation.

So the employees at K-zell ask two questions: Are we making money, and are we as productive as we can be? As Kammerzell explained, “If we can control those two things—profits and productivity—the rest of the metrics will take care of themselves. If you have a report showing that a job just shipped late, it’s too late to fix the problem. The job already shipped!”

The logic goes like this: If a job is late, K-zell doesn’t make as much money as it planned to make (or it loses money), because it’s spending more time producing the work. The more time a job takes, the more it costs. This happens for a variety of reasons, such as internal rework, operators not following procedures, or scheduling problems. But all those problems arise for the same reason: A certain task took longer than expected. It’s all about time.

“The only thing we do here is sell time. We don’t sell stainless steel countertops, we don’t sell bent angle, and we don’t even sell laser-cut parts. The only thing we’re selling is time, so hours are incredibly important to us,” said Darcy Funk, the shop’s accounting manager. “Everything we do, including our forecasting and our budgeting, is all based on hours. When we do the forecast, we’re going to look at how many productive employees we have in the shop—laser cutting operators, press brake operators, welders, and finishers—not me, not supervisors, just the people who are making us money.”

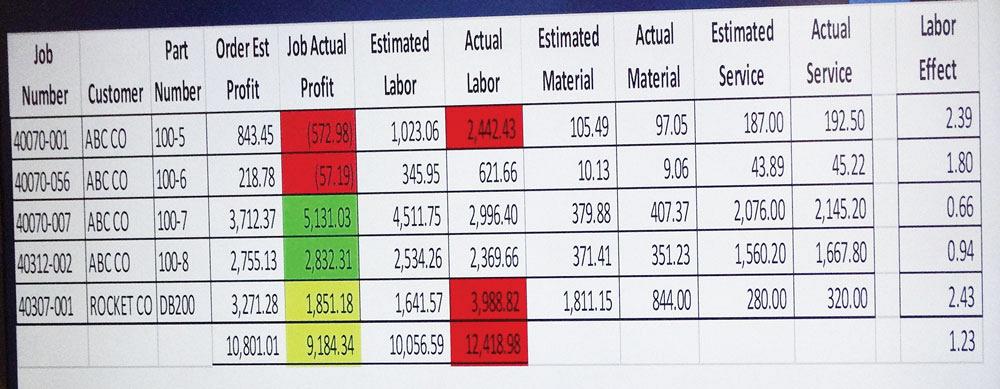

This sample of a daily report (with hypothetical customers) compares actual and estimated time for jobs and flags discrepancies. Green indicates more profit than expected, yellow indicates less profit than expected, and red indicates that the shop lost money.

Every month a typical direct-labor employee working a single shift has about 174 work hours available. K-zell then assumes that an employee should be working (clocked in) on a job for 80 percent of that time, or 139 hours a month. This also leaves time for general shop cleanup and basic maintenance. This is the number of hours per employee K-zell has available to sell.

“If time is what we’re selling, we need to know how much it costs,” Funk continued. “That’s why we use a fully burdened cost-per-hour. We locate every cost on the income statement—and I mean everything: electricity and other building costs, printer toner, other office supplies, indirect- and direct-labor costs, and more. We divide that cost by the total number of hours we have available. This fully burdened cost [plus the cost of purchased items like material and outside services] tells me how much money we need to make per hour to break even. If we’re going to make a profit, we need to sell the job for a little more than that.”

Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems in most shops use multilevel bill of materials (BOMs) as a foundation, but K-zell’s system, ProfitFab, takes a different approach. Its costing data starts at the operations level.

This goes back to the fabricator’s approach: It doesn’t sell products, as listed on a BOM; it sells the time to produce those products. Because K-zell “sells time,” every operation has a certain amount of time assigned to it based on historical data.

As Funk explained, “When we build a product, we add [the hours] for every single operation it’s going to go through, starting with engineering and ending with shipping.”

When, say, a laser cutting operator goes to a workstation adjacent to the machine controls, calls up the job and clocks in on the ERP system, the clock is running; when the operator finishes, and the work is ready for the next operation, the operator goes to the ERP system and clocks out. That records the time. If the time is more than was estimated, the shop either made less money than expected or lost money on that operation; if it’s less than the estimate, the shop made more money than expected.

At the end of every day, the company receives a report that details the two main metrics K-zell tracks: productivity and profitability. The profitability portion details every job that ships during a certain day. “Again, all I care about is hours,” Funk said. “We divide actual labor time by the estimated labor time. So 1 would be perfect; we met our estimate exactly. If we have more than 1, we used too many hours; that is, we lost those hours, which means we couldn’t sell those hours to someone else. If we’re less than 1, we of course did better than expected.” If an operation that day took longer than expected, it’s marked in red. The shop pays particular attention to the red jobs, to understand why those jobs took longer than expected and how to correct the issue going forward.

The productivity portion of the report shows how productive employees were: that is, what percent of the day did the operator spend clocked in on an order? And a greater percentage isn’t necessarily better. The report shows each employee’s productive and nonproductive hours. Less than 80 percent, and an employee’s time is shown in red. But if an employee is more than 95 percent productive, that’s a problem too. “We believe if they’re over 95 percent, they don’t have time to do maintenance or paperwork, so we mark it in yellow. And if we have too much yellow on the report, everybody’s working too hard, and we may need to hire more people. We look at this on a continuing basis.”

The most critical aspect of this report is that it’s daily, which allows K-zell to be proactive rather than reactive. After all, what good is a report showing problems after a job ships? “This allows us to fix problems while they’re happening,” Funk said. “If a product gets to a customer, and the work is returned to us, that will cost us more money and more hours.”

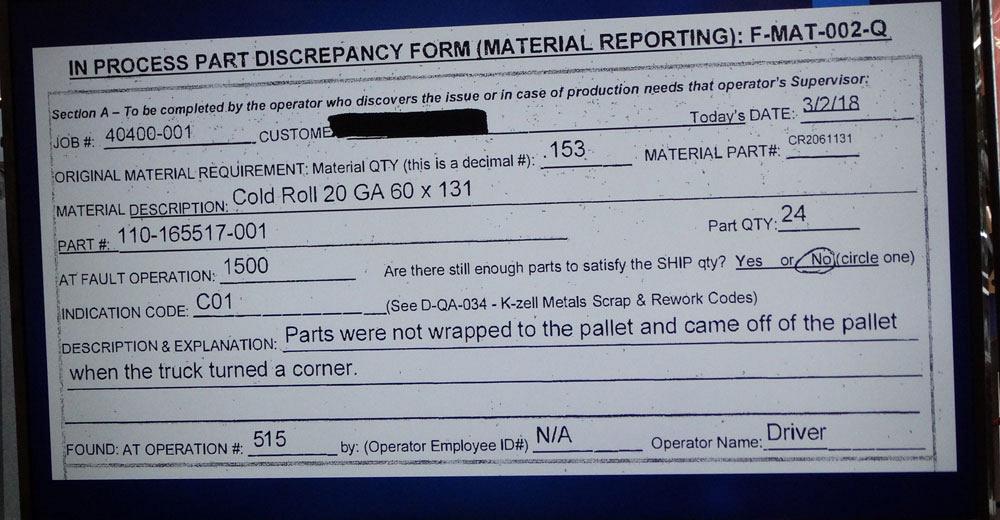

Funk then held up what the company calls an In Process Parts Discrepancy Form, or IPPD, which operators use to record every mistake made during production. Mistakes are tracked using around 60 indicator codes (what happened?) and 25 root cause codes (why did it happen?). Combining this with the at-fault employee information, the company tracks specifically where the production process failed. Were there equipment problems? Drawing errors? Was the procedure bad, or did the operator not follow the procedure? Is better training needed? By tracking every instance of errors, K-zell can identify problem areas and address the problems through process changes or employee retraining to make sure they won’t happen again.

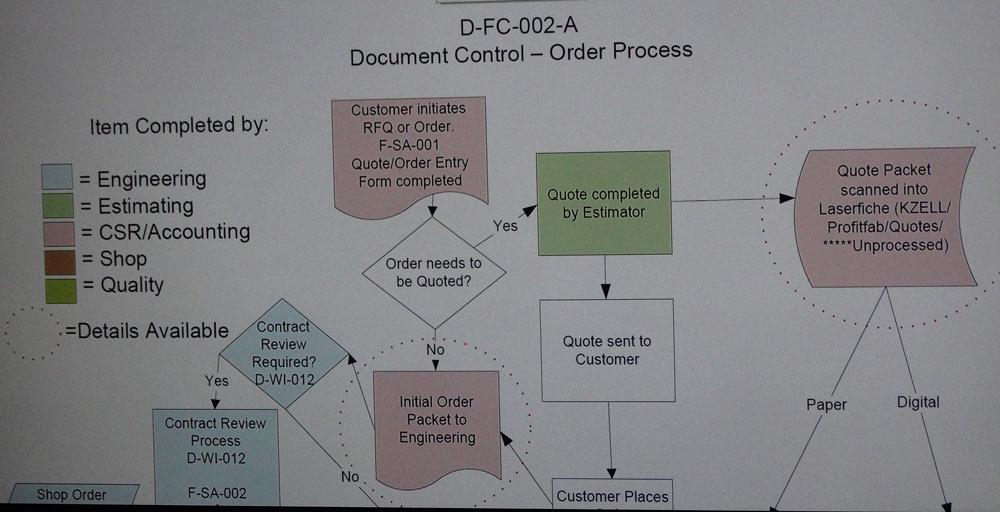

This shows one portion of a multilayer flowchart used to document procedures for ISO. When someone clicks on a particular step, he can access all documents and forms, including specific work instructions, associated with that step.

She added that the discrepancy report is not a disciplinary tool. “No one has gotten in trouble,” Funk said. “In fact, communicating this information is a critical part of everyone’s job.”

“One thing we’re very proud of here is that our warranty cost, in which a customer sends us back work that needs to be replaced, is just one-half of 1 percent of our gross revenue,” Kammerzell said. “This doesn’t mean we don’t have internal rework. But our external warranty costs are very low, because we catch the problems before we ship.”

The system isn’t perfect. For instance, Kammerzell said that operators sometimes have job-logging errors, when they don’t clock in and out of jobs properly. But overall, the system allows the company to perfect its estimated times, pinpoint the kind of jobs the shop excels in, and improve the overall operation.

Information Infrastructure

For this strategy to work, K-zell needs to give employees the tools they need to succeed. This includes an information technology infrastructure. The shop’s success relies on accessing job and performance data—not tomorrow or next week, but immediately. To that end, the company houses servers that communicate with the various operating systems on the shop floor’s machine controllers, from Windows 98 through Windows 10.

The fabricator makes it easy for everyone, from operators to engineers, to access current job data and necessary paperwork. Such performance tracking is vital, but in an ironic twist, if it takes too long for employees to track performance and fill out customer-specific paperwork, they have less time to be productive; that is, they have less time to sell.

“We use Laserfiche, an enterprise content management system,” Funk said. “It’s like a digital filing cabinet. When we scan and import it, the software reads the paper that goes into the system. It saves the text so that every single word on that document is searchable to help us find it quickly.”

The daily reports also help standardize and document best practices that form the basis for the company’s ISO 9001 documentation, which, again, to be effective needs to be accessible and easy to read by everyone in the shop. To do this, K-zell chose a low-tech solution and designed a simple, clickable flowchart. The flowchart details every operation the shop performs, from order entry, engineering, and receiving material to shipping and accounts receivable.

“When someone opens this flowchart [on a PC], they can zoom in and click on the step in the flowchart, then find associated visual work instructions, forms, OP [operational procedure] documents for ISO, and anything else they might need to complete this step in our process,” Funk said. “The system also automatically updates once a revision is made to any document. You can’t pull up the wrong revision.”

Technology Investment

K-zell’s careful approach to how it manages its time also helps its equipment investment strategy to get the best bang for its buck. Such investments include two robotic welding systems from Miller Welding Automation and Panasonic. Both robots are programmed offline, with fixture designs that incorporate laser-cut components, like tab-and-slot plates that fit together to hold a workpiece assembly.

Another key investment has been the shop’s Horn tube bender that can perform rotary draw bending as well as push roll bending and, the most critical part, especially for a high-product-mix job shop like K-zell, a Romer inspection system that communicates directly with the tube bending machine. “What really sets this machine apart is the way we inspect and produce our products,” said Jake Schofer, mechanical engineer. “After you bend a first article, you get within spitting distance, but it’s rarely perfect. There are just too many material variables. So after the first article, we use the Romer arm to take two measurements on each straight section.”

The system then compares the first article with the 3-D model and sends corrections to the machine’s bend program. “The software automatically makes updates to the program. On your second part, you theoretically should be perfect, and for us that’s been the case. This saves us an amazing amount of time. It’s a spectacular process, and it’s made my life significantly easier.”

The most significant recent investment sits at the back of K-zell’s plant. Installed in December 2017, the Bystronic fiber laser has load/unload automation and 10 kW of power. CNC Leadman John Bugay held a piece of 1/4-in. hot-rolled material. “The machine has built-in systems able to position the sheet for cutting in seconds,” said Bugay. “We’re able to cut this material at 409 inches per minute. This is the default parameter from the manufacturer with only a small modification to make the microjoints smaller, so we don’t spend much time hammering the parts out of the nest.”

All About Time

Bugay’s comment about microjoints is a critical point. It’s not just about cutting speed, bending speed, or any other processing speed, for that matter. It’s how fast parts move from one operation to the next. If a blank isn’t out of the nest and ready for one of the company’s four Bystronic press brakes, then the laser cutting operation really isn’t complete.

Ultimately, K-zell’s approach is about making the best use of time. After all, an hour wasted can never be gotten back. Knowing this, everyone spends their days making sure those wasted hours are as rare as possible.

Next year’s FMA Annual Meeting, which includes The FABRICATOR’s Leadership Summit, takes place March 5-7 in Nashville, Tenn. For updates, visit https://annualmeeting.fmanet.org.

K-zell Metals, www.kzell.com

Bystronic, www.bystronicusa.com

Horn Machine Tools, www.hornmachinetools.com

Miller Welding Automation, www.millerwelds.com

ProfitFab, www.profitfab.com

Laserfiche, www.laserfiche.com

Romer, Hexagon Mfg. Intelligence, www.hexagonmi.com

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Hypertherm Associates implements Rapyuta Robotics AMRs in warehouse

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI