- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Metal fabricator helps Ivy Leaguers race to the top

Columbia students compete in the classroom and at the racetrack

- By Eric Lundin

- June 12, 2018

- Article

- Shop Management

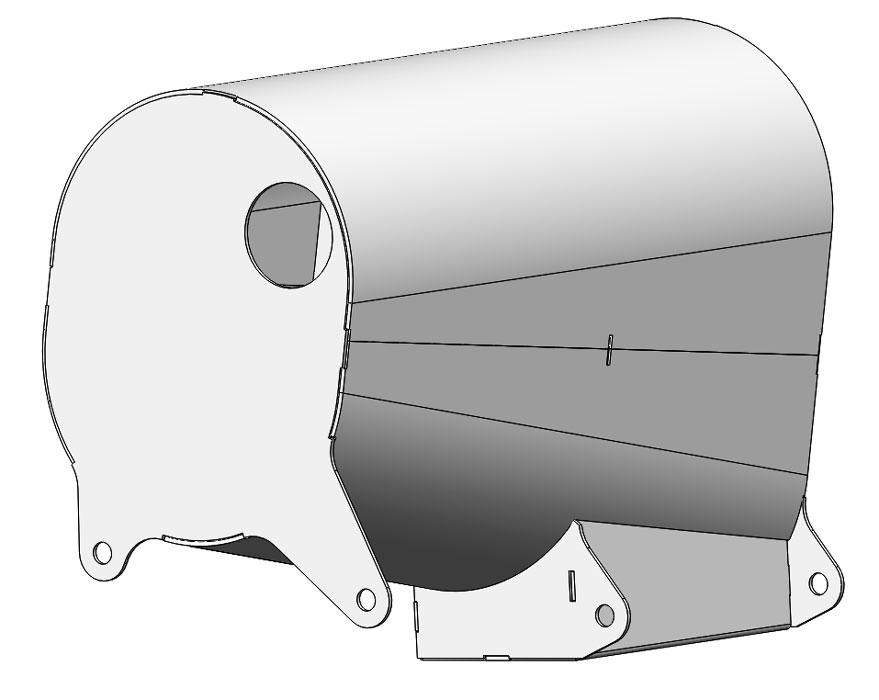

Figure 1

The asymmetric shape of the fuel tank made it a challenge to fabricate. Despite the unusual contours, the EVS team managed to replicate the drawing on its second attempt.

If you take a keen interest in university-level academics, you’re probably aware that the eight schools that make up the Ivy League—Brown, Columbia, Cornell, Dartmouth, Harvard, University of Pennsylvania, Princeton, and Yale—are among the most prestigious schools in the world. Their reputations are such that these schools reject roughly 85 to 95 percent of the potential students who apply.

The emphasis is on academics, but student life isn’t an unending cycle of lectures, books, papers, and exams. Columbia has a race car club, officially known as Knickerbocker Motorsports (KMS), the school’s Formula SAE team. This student club builds an open-wheel, Formula-style race car from scratch every year. After the car is completed, the team competes against schools around the world.

While Formula SAE is a racing event, this isn’t the whole story. Entries are evaluated on design, cost and manufacturing analysis, presentation, acceleration, skidpad, autocross, and fuel economy. In other words, these teams compete on many criteria, just as automobile manufacturers do. It’s much more than just a horsepower competition.

How Are We Going to Make This Part?

Although the student teams design, build, and field their cars, they don’t make every component. Usually they get some help from the industry, and the Columbia team often gets assistance from sheet metal and tube fabricator EVS Metal, Riverdale, N.J. The company has been one of the team’s most important sponsors, according to club member Jonathan Yang-Ming Chang.

“[EVS Metal’s] sheet metal capabilities were instrumental in getting suspension tabs cut and mounted, and this year they created an incredible fuel tank that was quite complicated to fabricate,” he said. “Huge thanks to EVS—we’re very grateful for their assistance and can’t wait to share our race results!”

Here’s the lowdown on the fuel tank from EVS Engineering Manager Nathan Lee: “The tank was designed in SolidWorks and fabricated from six parts in 0.063-inch-thick 5052 aluminum. Each part was cut on our 3,000-watt Amada ENSIS-series 3015 fiber laser.” The tank was then formed by bump bending on a press brake.

While rolling the tank was a possibility, the EVS team determined that rolling wasn’t feasible for this part.

“The large radius could have been rolled, but we would not have been able to achieve the precision that was required,” said brake technology lead Grzegorz Nysk. “It could have also been done using dedicated tooling, but that is costly and therefore not the best solution for this situation.”

In making the decision to bump-bend the part, the EVS team designated standard Amada tooling, a punch with a 0.8-mm radius, and an 8-mm V die, Nysk said.

EVS started with 40 hits, each with a pitch of 0.19 in. and 4.5 degrees of bend, but found that the ribs, or brake marks, were too severe, and the radius didn’t quite match the end plates. EVS developed a second process, one in which each bump was 1 in. of pitch for 2.36 degrees of bump. Presto! They had a fuel tank (see Figures 1 and 2).

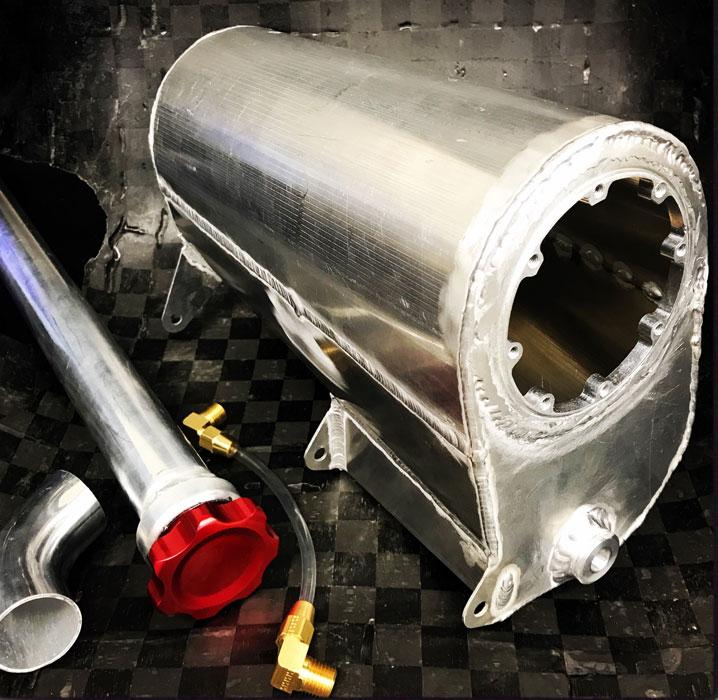

Figure 2

Understanding the entire process, from concept to manufacturing, provides valuable experience for the members of Columbia’s racing team. For the fuel tank for the 2018 car, bump bending was the best way to bend it’s contour in terms of speed, ease, cost, and accuracy.

“It took approximately 4.5 hours to tack the fuel tank together and weld the seams to get to the final product,” Nysk said.

Past, Present, and Future

Formula SAE cars aren’t the fastest racing cars ever built—the various rules usually limit the engine’s output to less than 100 HP—but because the cars average less than 500 pounds, the power-to-weight ratio is extreme. Columbia’s recent entry accelerates from zero to 60 miles per hour in less than 5 seconds (see Figure 3).

Lee recounted a few of the many parts EVS has made for the Columbia team: “Mounting tabs... lots of mounting tabs!” he said. “We have also made previous versions of the fuel tank, a brake pedal mount, large and small electrical boxes, a paddle shifter plate, and a chain guard.”

Truly, the EVS engineers and machinists involved in the project were almost as excited as the KMS racing team to have the opportunity to work on this year’s car build.

“The enthusiasm of the students at Columbia is always infectious,” said Vice President Joe Amico, a co-founder of EVS Metal. “We were happy to have the resources available to dedicate to both the fabrication of the suspension tabs and the design and fabrication of the fuel tank.”

EVS acknowledges the efforts of laser operator Aldo Ortega, brake operator Alfredo Flores, and welder Russell Zuidema for their dedication to the Knickerbocker project and Shannon Eggleton, who contributed to this article.

EVS Metal, 973-839-4432, www.evsmetal.com

About the Author

Eric Lundin

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8262

Eric Lundin worked on The Tube & Pipe Journal from 2000 to 2022.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI