Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Muza Metal Products perfects its sales and marketing strategy

Custom metal fabricator grows through customer collaboration

- By Tim Heston

- March 29, 2018

- Article

- Shop Management

Few in this business say they enjoy the request-for-quote game, at least if those RFQs are all about price. The customer sends out a request, and the cattle call commences. One job shop quotes an extraordinarily low price, and estimators at other fab shops pull out their hair. How on earth are they making money on this job? Soon enough, the work is out for bid again as (big surprise) the shop that quoted that insanely low price failed to deliver.

his doesn’t always happen, of course, but it isn’t rare either. Regardless, it’s no surprise that many custom fabricators focus their efforts outside the “price buy” arena.

They instead take the consultative approach and collaborate with customers to reduce the total cost of ownership. This sometimes entails a lower price for a sheet metal assembly, but it also can include a way of delivering products that leads to less-costly manufacturing at the customer’s plant. A fabricator with this strategy tries to be not just a parts supplier but almost an extension of the customer. All this certainly applies to Muza Metal Products.

Growth on East Murdock

The north side of the 600 block of East Murdock Ave. in Oshkosh, Wis., has been home to the Muza organization since the 1950s, when Leo Muza Jr., son of the founder, moved the shop into 606. At that point the company already had several decades under its belt; its roots go back to 1928. This year the fabricator celebrates 90 years in sheet metal.

In the 1970s a portion of the company split off to form an HVAC and architectural sheet metal shop on the north side of Oshkosh. Since then Muza Metal Products’ operations have filled 606 along with several other addresses up and down the avenue.

After the third-generation owner Tom Muza took over in 1997, things began to change in a serious way. The company employed about 80 people back then, and over the next 10 years the headcount doubled. This was in line with many progressive fabricators of the 1990s, those who embraced new technology and grew like wildfire. CNC became the norm, laser cutting machines were here to stay, and fabrication became a truly precision business.

The company added more CNC press brakes, expanded its powder coating capability, and even added some tube bending. In 2007 the fabricator also bought a robotic welding company and integrated that capability into the business. In 2008 it created a prototyping division, with machinery dedicated to especially low-volume and prototype work. And in 2010 Muza purchased a machine shop, which happened to be on the 600 block of East Murdock, where it still operates as part of the Muza organization.

Today Muza Metal owns four buildings on the 600 block, one of which (a 47,000-square-foot space known as Building 2) was built in 2012. Together the buildings add up to 191,000 sq. ft. of manufacturing space.

Not Your Private Equity Stereotype

Many in fabrication don’t have the rosiest view of private equity, especially when it comes to the “strip and flip” often associated with it. But not all private equity is like this. According to John Kriz, Muza’s president, this includes Milwaukee-based Wing Capital Group, which purchased the fabricating company from the Muza family in 2011.

“I have these conversations with prospective employees, whether they’re hourly, managers, or director-level executives,” Kriz said. “Wing Capital Group is extremely different. It’s not looking for a quick, one- to three-year turn on investments. The focus is on long-term growth and development. This includes not just long-term growth of the business, but also the development of leaders within the organization.”

He added that before the acquisition, Muza already had a strong management team in place. “Tom and the team, prior to the Wing acquisition, did a very nice job growing revenue at an aggressive clip, both the top line and bottom line. That made the business attractive to a lot of investors.”

The fabricator had diverse revenue streams as well, though Kriz conceded that “we were a little heavy in a few markets. Through the past five to eight years, we’ve been focused on diversifying further to protect our long-term stability, to be able to maneuver through potential recessions and downturns in specific industries or markets.”

Finding the Zebra

Revenue diversification often is looked at as the foundational building block for a sustainable custom fabricator. But it can be a double-edged sword. Say a shop lands an enclosure job that requires not just fabrication but also extensive electromechanical assembly. Sure, the work comes from a new industry sector for the fabricator, so at first glance it seems like a solid win. But it also requires assemblers to manage more assembly steps, insert more hardware and electronics, and manage complex work flow.

Regardless, the fabricator takes a deep breath and dives in. Within weeks, the customer calls. Enclosures are missing hardware or have the wrong hardware type. Or perhaps the wrong parts were assembled to the wrong enclosure. Or perhaps there was a last-minute design change, and the fabricator wasn’t informed. Whatever the problem may be, the customer is angry.

Kriz emphasized that this exact situation didn’t happen at Muza, but it could have if the shop expanded its assembly capability without the right strategy. A shop’s strengths should define the target customer, not the other way around. The people at Muza call these target customers their zebra accounts—companies you can spot in a crowd.

“In 2017 we began working with a local marketing firm, Dynamic Insights out of Neenah [Wis.],” Kriz said. “They helped us come up with our go-to-market brand strategy, and it really emerged from our need to diversify. We now have six industry verticals [manufacturing market segments] that we focus on in different regions within the United States. And now we have a new business development manager whose primary role is to look for those diversified markets.

“When we find a ‘zebra,’” Kriz continued, “we build a solid partnership.” That partnership is key, especially when the goal is not only to diversify but also offer more value-adding services.

To that end, managers at Muza have taken a two-pronged approach: identify those zebras, and make sure Muza has solid production and quality processes to serve those zebras. No one wants to oversell and underdeliver.

Muza representatives visit customers, talk with them about their challenges, then suggest changes that could make the process easier. This could entail a design change to a sheet metal enclosure to error-proof subassembly or final assembly; a new delivery method for sheet metal parts (say, a kanban replenishment involving frequent deliveries of small batches); or even a new way to present those parts to workers at a customer’s plant (like an enclosure oriented in a certain way for easy retrieval and installation).

Kriz described a job with a customer that began working with Muza in 2017. The customer was managing close to 100 part numbers for a certain assembly. Muza engineers worked with the customer, analyzed the design, and successfully reduced the part number count to one. “Managing all those parts, this company used to get only one enclosure product out a day. Now the company receives a finished enclosure from Muza, and assemblers there fill it with electrical components. They now ship six or seven of these a day.”

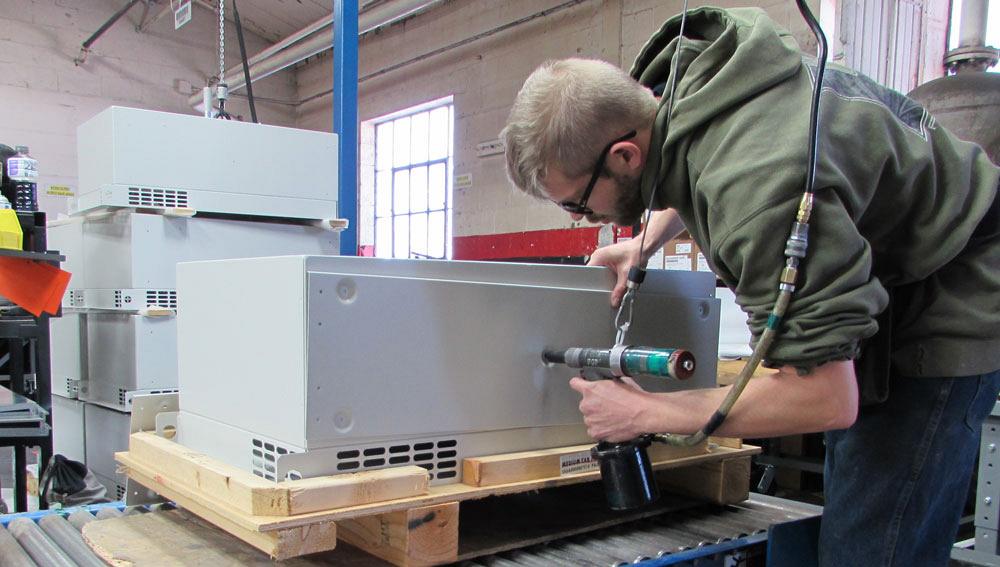

Muza Metal’s expanded assembly area includes rotating roller tables, scissor lift tables, standard work, dedicated point-of-use tools, and hoists, all there to make the assembler’s job easier and safer.

In this sense, Muza doesn’t simply sell sheet metal fabrication capacity to its zebra customers; it sells process improvement. “We’ve created our strategy in what we call our ‘sales war room,’” Kriz said, “basically a room with dry-erase paint on the walls. We’re looking to capture both opportunities with new customers, as well as further develop the business with our current zebra accounts. For example, we’ve identified our top 10 customers, and we’ve found that we’re supporting their needs at only one or two of their locations. And these customers each have between 10 and 30 different manufacturing or assembly facilities throughout the United States.”

All this, however, must be built on a solid foundation of reliable quality and delivery. This started with clear, concise, photo-filled, laminated work instructions accompanying every assembly, along with clear standards and quality procedures to ensure every assembly that leaves the facility is a good assembly. The company has divided assembly work into stations, with specified takt times based on the job and product family. All hardware and tools are organized at the point of use.

Kriz added that the most important improvements have dealt with safety and ergonomics. “We now have scissor lift tables and rotating tabletops so assemblers can simply rotate the work rather than having to walk around a large electrical enclosure.”

Other material handling aids include rail systems, hoists, and conveyors—all of which prevent assemblers from having to break their backs when manipulating large cabinets. At this writing, the company is creating a second assembly area that will mirror the capabilities of the first, complete with lift tables, conveyors, and rotating devices.

“Over the past two years we’ve invested $100,000 on just one specific assembly line in the plant,” Kriz said. “That helped us improve quality in that line by 95 percent.”

The assembly shop has new lighting too. When dealing with intricate assemblies, bad lighting can lead to some expensive mistakes. After all, how can an assembler ensure an enclosure has the right hardware, right parts, and is free of any cosmetic defects if he can’t see what he’s doing?

People

Recently Muza worked with its marketing firm to create literature—dubbed “Why Muza?”—to hand out at trade shows and sales meetings. But it occurred to managers that the company also needed “Why Muza?” literature for prospective hires.

The company’s headcount is now at about 265, and managers hope to increase that by another 10 to 15 percent this year. That’s no easy task for any fabricator, and even harder when the local unemployment rate is less than 3 percent.

To that end, the company touts its core values and opportunities. “About half of our 32 people in the office—engineers, estimators, IT, supervisors—came from the shop floor (see sidebar). “We have opportunities,” Kriz said, “and we have data that shows those opportunities are there.”

This, he added, is what makes growth so important, but the nature of that growth matters. The company doesn’t want to grow just for growth’s sake. Besides giving a business the opportunity to reinvest in equipment and software, sales growth gives existing employees opportunities for advancement. But if that growth comes on the back of one industry or one large customer, it won’t be sustainable. It’s why diversity remains so important.

“When we strategize, we’re thinking not just about our 265 employees, but also the 265 families they help support.”

People want opportunity, but they also want stability during good economic times and bad. Muza’s strategy, Kriz said, is to provide both.A Career Path Story

Mike Selner knows his way around a press brake. He spent four years as a brake operator and another eight as a second-shift supervisor. He’s been taught how to manage on the shop floor, getting a degree in supervisory management from Fox Valley Technical College, Appleton, Wis. Now, as new business development manager, he’s leading Muza’s charge to grow and diversify the business.

“I started out on the press brake at Muza in 2002,” he said. “I rose through the ranks and about three years ago ended up on the front line in sales. I know the products we’ve built over the years, and I know our capabilities. I’ve touched our parts; I’ve lived them. And even more important than that, I know the kind of work that doesn’t fit. If I see something that doesn’t fit, I realize it right away, and I move on to the next opportunity.”

Selner’s career path exemplifies Muza’s promote-from-within ideal. But as Selner explained, he didn’t rise through the ranks simply by answering internal job postings. Along the way, his managers asked about his future aspirations and gave feedback.

“Chuck Galipo [director of customer solutions] told me that I should look into sales. But I said, ‘Well, I’m a supervisor. I’m a hard-core operations guy. I’m not sure I want to go on the road.’ But he said, ‘You’re good with people, and you can talk someone’s ear off about the right things. So why not give it a shot?’”

So he did. At this point the company had invested quite a bit in his development, and that development was paying off. That supervisor training he received at Fox Valley Technical College is a prime example.

“On the people-skills side of it, going to technical school was very helpful. It was great to have those additional resources, rather than just to learn by trial and error. Muza helped me out with tuition reimbursement. And what I learned there, I found I could take it right to the floor. It could be diffusing conflicts, managing through stressful times, and things of that nature.”

Such staff development could be looked at as the fourth leg of the business-growth stool. A shop needs machines and software, it needs refined processes, and it needs a solid sales strategy with target customers in diverse markets. But above all, it needs talented people—and the more a shop can do to support that talent, the better.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI