Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

How one metal fabricator navigates change

Larsen Manufacturing adapts, grows, and thrives

- By Tim Heston

- June 6, 2018

- Article

- Shop Management

David Larsen knows how to read the ripple effects of big changes, and as co-president and one of the founders of Mundelein, Ill.-based Larsen Manufacturing, he’s made quite a lot of them. What was once a small custom stamper is now a $45 million, 225-employee diversified metal manufacturer with an additional location in El Paso, Texas, and a manufacturing partner in Hong Kong, which has been serving the market in Asia since 2005.

The history of Larsen’s company is a study in change management. The organization was launched in 1999, but it has roots in a predecessor stamping company that goes back to the 1940s. The story reflects a lot on the state of metal fabrication and manufacturing in general. If a manufacturer isn’t changing, it’s dying.

Ripple Effect

Larsen uses the ripple-in-the-pond metaphor to describe how he’s navigated the company’s growth over the past 19 years. Any company leader needs to look outward for opportunity and to follow customers’ changing demands. If customer demands don’t change dramatically, then a fabricator can continue on, like the glassy surface of a tranquil pond. But if markets change, then a fabricator needs to change with them.

“This is as if you’re throwing a rock into a pond,” Larsen said. “It’s going to cause a splash. It can be painful.” But after a while, the waves subside to ripples and the business marches on. The trick, Larsen said, is managing the splash and ripples so water doesn’t splash clear out of the pond. If that happens the pond doesn’t have any water left—and the plant shuts its doors.

A Fresh Start

When Larsen said he wanted to launch a new metal stamping business in 1999, people thought he was crazy. By that time globalization was in full force, tool and die work had fled overseas, and manufacturing stateside was said to be dying. The majority of manufacturing that remained was low-volume, high-mix work, so why launch a stamping company?

But Larsen had been around manufacturing all his life, he knew the demand for stamping was there, and his family had decades-long relationships with those who still needed such work. After all, no matter how quickly a laser cuts and a press brake bends, it’s tough to beat the done-in-one productivity of a well-designed prog-die operation.

His grandfather, Leonard Larsen Sr., joined a tooling and stamping company called Algonquin Tool in the 1940s, and by the 1950s the company entered the electronics world, manufacturing TV tuners and enclosures for companies like Admiral Television. In 1955 Algonquin Tool became Electro-Metal Products Corp., or EMP.

David’s father, Leonard Larsen Jr., joined EMP in 1960, and in the 1970s and 1980s the stamper continued to make a name for itself in consumer electronics and other consumer products. During these years David was working in manufacturing, but not in metal stamping. “I didn’t follow the family trade. I learned the tool and die trade working at a mold shop while going to high school, when I learned all about the injection molding industry.”

But by 1995 David decided to join the family business, and it was quite a time to join. His father was getting ready to retire, so what would be the next steps? Considering the state of the industry, what would be the best way to move forward? After much discussion, Leonard Jr. decided to sell the business to another stamper in the Chicagoland area. Selling the business seemed to be the best strategy. He knew the change would create some ripples, but people would be able to navigate through them.

Unfortunately, as can happen with acquisitions large and small, things didn’t work out entirely as planned.

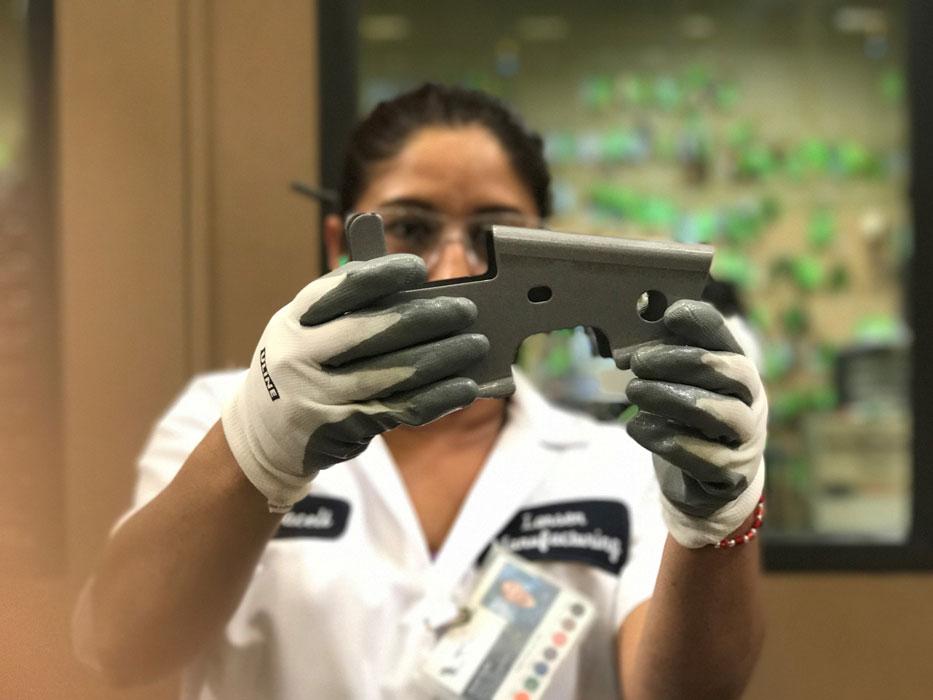

Larsen Manufacturing ramped up its contract manufacturing, including assembly and electromechanical assembly, in 2014 and 2015.

“When I joined EMP [in 1995], the company ran well, but the customer base was flat,” David said. “It was determined that, considering the market at the time, it really was the best time to sell the business. The acquisition itself went well, but the final outcome didn’t.”

The new company had a very different culture and management focus. It was as if a boulder were thrown into the pond, splashing water onto the shore; the water’s smooth surface became a tumult.

David knew everyone who worked at EMP and he knew its customers, many of whom had been with the stamper for decades. He recalled his father bringing home metal toys that EMP made for companies like Ertl®, those iconic trucks and farm tractors that you see today on “Antiques Roadshow.” (“Back then you either were a Tonka family or an Ertl family. We were an Ertl family.”)

David, along with his twin brother Denis, decided to continue the family legacy and dive into the stamping business on their own, opening Larsen Manufacturing in 1999.

“It was the right time to restart the family business under the Larsen name, so my twin brother Denis and I went for it,” David said. “I knew the customers and the engineers at those customers. They couldn’t promise me the work, but they said that if you build it, they would come out with their quality and engineering staff and see if we could be approved to be a [metal stamping] supplier.”

Put simply, EMP’s legacy customers weren’t happy with their current situations, and from this, the Larsens saw opportunity. The brothers rented a 10,000-sq.-ft. building in an industrial park in Mundelein, Ill., and they launched Larsen Manufacturing with some used toolroom equipment, four new mechanical stamping presses, and a team of six people. Denis handled production and quality and David handled the front office sales and engineering.

Starting small had its advantages. The brothers were able to meet demands that larger, less agile companies just couldn’t. David recalled receiving an order one day for 5,000 parts. Within hours the die was in the press, and by the next morning, those parts were in customers’ hands. Within that first year, the startup had drawn back nearly 80 percent of EMP’s customer base.

“It really was a rebirth,” David said, “a blank sheet of paper.”

It was a good time for a rebirth, too. Computers and CNCs were beginning to dominate the industry. Technological changes combined with globalization made manufacturing itself more dynamic. No manufacturer—and no stamping shop in particular—could sit back and conduct business as usual for decades on end.

Would the brothers have been able to make changes so quickly if EMP had remained in the family’s hands? It’s difficult to say, but David said he doesn’t think so. The new business, new manufacturing space, and new technology planted the seeds for an entirely new kind of business, one that EMP workers of the 1960s and 1970s probably wouldn’t recognize today.

Larsen’s management team—from left, David Larsen, co-president; Rob Kalkowski, vice president of sales; Denis Larsen, co-president; and Bob Kalicki, CFO—stands by the company’s newly installed powder coat line.

Move to Custom Fabrication

The Larsens have a longtime connection to El Paso, and in a circuitous way, the city led them to the world of custom metal fabrication. Denis ran EMP’s plant there, and in 2001 he helped launch a stamping facility for Larsen Manufacturing. By the mid-2000s Larsen purchased the customer base of a Juarez, Mexico, stamping plant, then moved that work to the El Paso location. Orders included conventional stampings as well as work that involved “soft tool” custom fabrication—punching, laser cutting, and press brake bending. Up north, Larsen’s customers in the Midwest continued to ask about soft tooling as well.

Timing forced the issue. It was 2008, and the bottom was just beginning to fall out of the economy. In 2009, under the stress of the Great Recession, the people at Larsen Manufacturing took a leap, bought new fabrication equipment from Amada and others, and launched a custom metal fabrication division.

Since then custom fabrication work has blossomed, and truth be told, rather than being a “division” of a larger stamping organization, metal fabrication has become an equal part of the company’s broad portfolio of services—similar, in fact, to other organizations on The FABRICATOR’s annual FAB 40 list.

The company has had its own toolmaking capability since the very start, and it also uses machining to make components that go on larger sheet metal assemblies. And besides offering stamping, custom fabrication, and welding services (including robotic welding), Larsen expanded into mechanical and electromechanical assembly and (as of first-quarter 2018) powder coating.

“We brought powder coating in-house this year because we were having quality and delivery issues sourcing it out,” David said. “We know our competitors, and we also know that they’re probably having the same trouble we had when we outsourced powder coating, so we give them a fair price and help them out.”

In that respect, Larsen remains old-school, fueled by the family’s long history in metal manufacturing, where everyone knew everyone else, and a shop didn’t hesitate to help a friendly competitor in need. At the same time Larsen Manufacturing is very new-school, aggressively pursuing new services.

But a danger lurks behind all this diversity, and it has to do with David’s ripples-in-the-pond metaphor. Change too quickly or in the wrong manner—without open, honest communication among all—and you throw a rock instead of a pebble and make unsettling waves instead of ripples. So how do the Larsens manage the change?

To begin with, David said, leaders need to know that every change comes with a splash; but just because it does, they shouldn’t be afraid to make it. Take powder coating. “Yes, some questioned that,” David said. “They thought, ‘Isn’t this outside our core expertise?’” He added, though, that the initial splash, if controlled, ends up smoothing out with time, as people adapt to the new normal.

That’s fine, but how does Larsen control the splash? First comes careful timing. After a change, the Larsens try not to throw another pebble into the pond. They wait for the splash and the ripples to subside.

When possible, they make sure the splash isn’t too large. They start small. “For instance, when we launched into assembly in 2014 and 2015, we began small, in a way that wouldn’t jeopardize our other areas of business,” said Riley Kelly, Larsen’s marketing analyst.

She and other company sources added the market dictates how quickly the company needs to change too. Moving too slowly isn’t an option, so difficulties are bound to come up. Coordinating a supply chain for complex electromechanical assembly, for instance, isn’t for the faint of heart.

Hence the need for the right resources and expertise. When the company brought in powder coating, it hired experienced people who eased the transition. The same happened earlier when the company brought on metal fabrication during the Great Recession, when a number of people with experience in fabrication happened to be looking for work.

Another key to navigating change involves the business’s organization. If someone buys from Larsen Manufacturing, they work with a sales representative who might focus on a type of company or industry, but they also work with Larsen’s entire process portfolio. When prospective buyers visit the company’s website, they see the basic breakdown: metal stamping, metal fabrication, and contract manufacturing, which includes mechanical and electromechanical assembly. They also see some specialty equipment the company fabricates, including a machine brand the Larsens purchased called the WAND depaneling system, which is a good fit, considering Larsen’s history with customers who make printed circuit boards.

The view from inside the company is different. The brothers never forgot the efficiency of the early days and how quickly that small shop responded. They knew they had to scale up the business, but they also wanted to keep that small-company feel and adaptability.

Today the company is organized into three business units, each with its own management structure: stamping and toolmaking (including general machining); metal fabrication and contract manufacturing, which includes assembly; and paint and specialty fabrication. A quality department supports all three.

The company groups fabrication and contract manufacturing together because they share similar production scheduling requirements that entail many discrete steps—very different from the stamped components that emerge from a press with a prog die.

What is specialty fabrication, exactly? “Our specialty fabrication business unit consists of projects that require more space,” said Kelly. “There’s more prototyping, more trial and error, larger projects, and more creative endeavors.”

Specialty fabrication is about complexity; it’s work that requires specific hands-on expertise, from trial-and-error machine setups to precise gas tungsten arc welding. The business unit also focuses on large assemblies that need more space to put together. Kelly added that paint is grouped with the specialty fabrication because they share a space in a building a few blocks away from Larsen’s headquarters. This building also houses high-speed production line assembly work for customers with higher-volume requirements.

Each business unit has its own profit and loss statement and, in this sense, operates as a small business. But sources said that the business units also haven’t devolved into fiefdoms (all too common, especially at very large companies). For one thing, they need each other; for a growing amount of work, the divisions collaborate to ship products out the door.

Rob Kalkowski, vice president of sales, added that the collaboration works because each division knows that many customers wouldn’t be with Larsen if it didn’t offer such a wide range of services. “Everyone knows they’re stronger together.”

Responding to changes in customer demand, Larsen Manufacturing ventured into custom metal fabrication starting in 2009.

What’s Next?

The employees at Larsen Manufacturing face similar challenges as others in this business do. They work with customers on inventory stocking and replenishment arrangements, while trying not to hold too much inventory in-house. “Especially these days, with material prices how they are, holding too much inventory ties up a lot of cash,” Kalkowski said.

Like others, the company is navigating through a world of trade-war saber-rattling, tariffs, and material price hikes. Most customers are fully aware of the situation, Kalkowski said, but Larsen is also paying close attention to its raw stock purchasing practices, taking advantage of deals when it finds them.

The Larsens have a manufacturing legacy that goes back generations, and it has played a role in the company’s evolution. David and Denis’ grandfather, for instance, knew the owners of the company that sold its Mexico operation to Larsen back in 2009. “Our families had business relations,” David said. “Our grandfather helped that company back in the day.”

That tight network has helped companies like Larsen grow through the years. Customers came by word-of-mouth, as did many employees. Today that network is still there, but it’s now not quite expansive enough to feed the industry’s need for skilled labor. And from the sales side, word-of-mouth can get you only so far.

Several years ago the Larsens knew they needed to ramp up their marketing efforts. Kelly, who was hired last year, helped give the website a new look—a common trend among fab shops these days. But a new look doesn’t by itself make much of a difference. What really has made an impact is the company’s online presence in general.

“I call it the buyer’s journey,” she said. “Buying in manufacturing is changing with the new generation coming into the workforce. We need to adapt to those changes. More sales leads are coming from online. You wouldn’t expect purchasing agents and others looking for our services to simply Google to find suppliers, but they are.”

Larsen’s latest push online is really just another adaptation, another ripple in a pond that hasn’t had still waters for 19 years. This reflects the nature of modern manufacturing in general. It’s becoming harder for a shop to stay the same and keep the waters calm.

A periodic splash of change followed by continual ripples—as the company expands, grows, and improves—has become the new normal.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI