Principal

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Problem solving in metal fabrication: Look past the symptom to find the root cause

Tackle the root cause to put problems to bed—for good

- By Jeff Sipes

- September 14, 2017

- Article

- Shop Management

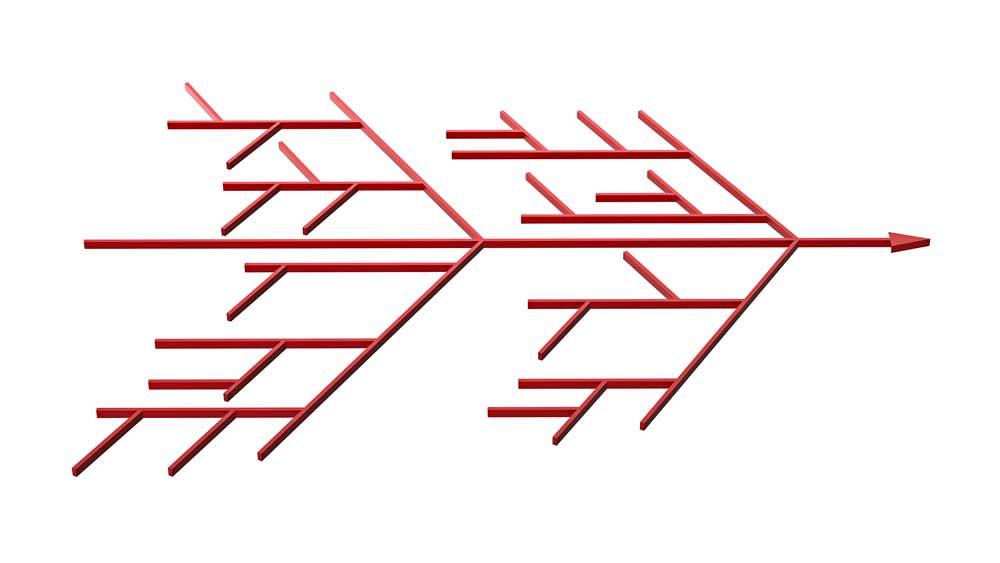

In this illustration of the fishbone diagram, the arrow on the right points to the effect, and the four lines connecting to the vertebra cover four main topics: man, machine, materials, and methods. Lines connected to them show the chain of cause and effect.

Does it seem like you deal with the same problems over and over? It could be a quality issue, a schedule problem, a personnel matter, or numerous other things. If this sounds familiar, you may be dealing with symptoms, not root causes.

Every time we spend time reworking “solutions,” we incur the waste of precious resources. It can be frustrating and distracting. Yet until we address the root cause, the non-value-added cycle will continue.

Root Cause Versus Symptom

It is easy to toss around the term root cause when discussing process problems. The boss says, “I want you to get to the root cause!” The engineer shares her findings from her root cause analysis. The kaizen team spends the day focused on understanding the root cause. We frequently hear the term being used, but rarely do we question if we are honestly and rigorously getting to the actual root cause.

So what is a root cause, and why is it so important? Let’s start by contrasting a root cause with a symptom. Webster’s defines symptom as “Something that indicates the existence of something else.” Let’s apply this in an industrial setting. Kaizen team members look at a problem and uncover a symptom—but that’s just the first level of analysis. If they stop at the first level, develop and implement a corrective action, and expect a permanent resolution, they will be disappointed when the problem reoccurs.

Why? The first level of analysis points to something deeper, something that provides enough evidence to keep on analyzing. But it is easy to get fascinated with an obvious answer to the problem being addressed (that is, the symptom), implement the quick solution, and then move on to the next problem. This feels good and seems efficient. But the elation is short-lived when the problem reoccurs. If you “fix” the symptom, then at best you have put a Band-Aid on the wound.

The root cause is the fundamental reason the problem occurred. Another definition describes root cause as a factor that caused a nonconformance and provides an opportunity for a permanent fix. If we identify and implement a solution addressing the root cause, the problem should not reoccur.

The absence of a root-cause focus leads to a vicious cycle that produces little or no improvement. If we stop wasting time on symptoms and spend our scarce resources understanding and addressing the root causes of problems, we free up resources to tackle more important issues.

Two techniques, the 5 Whys and the cause-and-effect diagram, can help you identify root causes. Think of these as everyday problem-solving tools that many people in your organization have proficiency to use … and are empowered to use.

The 5 Whys

The 5 Whys, a structured way to move from an obvious symptom to an actionable root cause, can be done by just one person as well as by groups large and small. All people need is a whiteboard, a flip chart, or a piece of paper.

Start with the issue at hand, such as a machine that does not meet the defined takt time. This is a symptom, and at this point it is not clear what action to take.

Next, ask “Why?” five times. There is nothing magical about the number 5, but it seems to be an effective target to get to an actionable item. The closer you get to the fifth “why,” the more specific the response.

We start with, Why is the machine not meeting the takt time? A pneumatic material pick-and-place device is moving too slowly. The kneejerk response would be to simply turn up the air pressure. But would that fix the problem? No.

Instead, we ask, Why was the device moving too slowly? There was debris in the machine’s air filter. Again, the quick corrective action would be to clean the air filter and start running again. But this still does not address the root cause, because the debris had to have come from somewhere.

As we work through the rest of the questions, the root cause becomes clear: There was a breakdown of the plant’s main air filter, which not only contaminated the parts-handling device, but also had the potential to affect the plant’s entire air system. Fixing the symptoms (not meeting takt time, handler moving too slowly, debris in the machine’s filter, etc.) was not going to make the problem go away.

Cause and Effect

Have you found yourself in a problem-solving meeting where there is lots of talk and little documentation? People spout ideas that are quickly forgotten. Everybody has an opinion, and sometimes people even present some data. But it’s still a verbal free-for-all that expends lots of energy yet produces few results.

The cause-and-effect diagram can help by stripping away the noise and bringing structure to the analysis. You may also know this tool as the Ishikawa diagram or the fishbone diagram. It’s most effective when used in a small group with a facilitator.

First, decide what specific effect (that is, problem) you want to analyze. The effect might be that you run out of material at the pipe welding station, or the throughput time in the pipe welding cell is 25 percent too long, but it cannot be both. One might be related to the other, and the diagram you generate will probably show this relationship. But for this method to be effective, you must focus on one effect, then build the diagram around it.

Next, draw the fishbone skeleton. Make a box to the right side of the space for the effect. Draw the main vertebra, a straight line extending from the box across the space to the left. Add four lines with two going up from the horizontal vertebra and two going down. Spread the four lines out so there is room to work in between the lines. Next, label each of the four lines as man, machine, materials, and methods—the four main topics of the fishbone diagram. Finally, write the effect in the box.

Now start brainstorming. Pick one of the four topics and ask the group for ideas. Specifically, what related to that topic (man, machine, materials, or methods) could have caused the effect? As participants offer ideas, write those ideas by each topic. This is brainstorming, so do not judge and do not go into detail.

For an idea just placed on the diagram, ask if there are any causes of that cause (that is, a cause is an effect of another cause). If so, draw a line below or above the first idea and write the new idea on the line. Note how the fishbone structure takes shape. Repeat the questioning for this idea until there are no more responses. Then go on to another one of the four topics.

Once you populate the fishbone diagram, ask the group to step back and get a feel for the quantity and type of potential causes generated. This is a picture of all that verbal noise. Seeing it all at once helps keep the process objective.

Finally, ask the group to identify the ideas that are most likely the major causes of the effect—that is, the critical few. There should be no more than three major areas of focus. Finally, develop a plan to dive deeply into the critical few, and get on with improvement!

A Root Cause Analysis in a Kaizen Event

As I write this article, I happen to be leading a kaizen event at a client. The first day I coached the kaizen team to reflect on the current-state analysis and how we used the 5 Whys and the cause-and-effect diagram. Overall feedback was positive. Almost everyone had not seen or used either of these analysis tools.

The tools gave their problem-solving effort focus. They no longer talked about ideas but did nothing. No longer were they sidetracked, tackling symptoms instead of the root causes. They focused on the critical few, and implemented changes that made a real difference.

The Long View

Countermeasures applied to symptoms provide short-lived results … at best. Countermeasures applied to root causes put problems to bed so they don’t come back.

Are you empowering the people in your organization with knowledge, authority, and the expectation to be effective problem-solvers? The 5 Whys and the cause-and-effect diagram provide a great place to start.

Jeff Sipes is principal of Back2Basics LLC, 317-439-7960, www.back2basics-lean.com. Want to know more or have a suggestion for a future Continuous Improvement topic? Contact Sipes at jwsipes@back2basics-lean.com or Senior Editor Tim Heston at timh@thefabricator.com.

About the Author

Jeff Sipes

9250 Eagle Meadow Dr.

Indianapolis, IN 46234

(317) 439-7960

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI