Owner, Brown Dog Welding

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Giving the right way is a win-win for metal artists

- By Josh Welton

- June 22, 2017

If you’re an artist, there is a 99.9 percent probability that you’ve been asked to donate work to a charity. In fact, if you create art, there’s a decent likelihood that about half of your incoming emails revolve around charities and nonprofits kindly inquiring in regards to your generosity. Decent humans often find it difficult to turn away these queries.

The fundraisers will also tell you about the benefits you’ll enjoy: The added exposure for your brand and tax write-offs for your business. So, on top of the obvious benefit of easing your conscience, you’ll also come out OK on the financial end too, yeah?

Not necessarily. Besides looking into the organization you’ll be helping, researching how donation laws work are in order as well. Not every cause is worthy, nor does every fundraiser work the same.

First Things First

Make sure the potential organization is legit. A few years back, the Tampa Bay Times and the Center for Investigative Reporting put together an exhaustive list ranking the worst charities in America. The villains dress as heroes and often times choose a name that closely resembles a highly regarded organization, as the Kids Wish Network did. This is NOT the same as the Make-A-Wish® Foundation. From the report:

“Every year, Kids Wish Network raises millions of dollars in donations in the name of dying children and their families.

“Every year, it spends less than 3 cents on the dollar helping kids.

“Most of the rest gets diverted to enrich the charity's operators and the for-profit companies Kids Wish hires to drum up donations.

“In the past decade alone, Kids Wish has channeled nearly $110 million donated for sick children to its corporate solicitors. An additional $4.8 million has gone to pay the charity's founder and his own consulting firms.”

Kids Wish is not an outlier. Too many of these predatory organizations exist, and they’ve stolen literally billions from folks who think they’re doing the right thing.

Last year the Wounded Warrior Project fired two execs for over-the-top travel and event spending. Steven Nardizzi and Al Giordano were paid nearly $1 million a year to run WWP. Since their exit, the Project has changed for the better, at least according to the Better Business Bureau.

In 1995 the head of the United Way of America was sent to federal prison for using donations to fund his journeys on private jets, limos for mistresses, European vacations, and condos in New York City and Miami. William Aramony is the poster boy for the dark side of charitable organizations. UWA may have cleaned up its act to an extent, but massive overhead and strong-arming corporate donations are still an issue. I actually deal with the latter at my day job.

And for giant organizations such as the Red Cross, it’s not always a structural scheme; it could be a group of rogue volunteers. This was case in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, when fake claims diverted millions that were supposed to help victims of the natural disaster. In this instance, the Red Cross was just one of the charitable organizations used by thieves, and in the end, it was proactive in helping to prosecute the perpetrators and recover funds. It does, however, show the vulnerability of larger-scale nonprofits.

I’m not going to tell you to never support the Red Cross, or the United Way, or the Wounded Warrior Project. Please do your own research. Just don’t blindly give to ease your conscience.

Value Your Work

Maria Brophy is the wife of surf artist Drew Brophy, and as successful as Drew has been with his work, Maria has equaled it as both his manager and counselor who speaks to artists trying to navigate the business side of art. A piece she wrote years ago is what opened my eyes to the negative side of giving work away, and how to maximize the impact I can have on causes I believe in … while not going broke.

The two biggest things I took from that post seven years ago were to concentrate on two or three charities that mean the most to me personally, and to pay attention to how the donation works. The latter includes both understanding tax laws and grasping the negative impact charity auctions could have on the value of your work.

There are needs everywhere. I prefer to give back locally or to causes I’m familiar with on a person-to-person level. Smaller groups aren’t immune to misappropriations or embezzlement, but knowing the history of the charity or nonprofit, and the people who operate it, is a plus.

Know the Tax Laws

Politicians are responsible for one of the most misunderstood chunks of the artist-charity interaction. Shocking, right? The Tax Reform Act of 1969 was Congress’ response to former President Nixon and the presidents before him who donated their pre-presidential papers to the National Archives for a gigantic tax write-off. Congress felt that the presidents were taking advantage of a law that gave artists who donate work a tax benefit that paralleled what they would have received if they sold it to a private collector. They were entitled to a “fair market value” write-off. Nixon, and those before him, knew their writings were worth hundreds of thousands of dollars on the open market and felt, as “artists,” they should be given the write-off thusly. The Tax Reform Act closed this loophole. A latent effect of this new law was that donations from artists to museums across the country came to a screeching halt.

As an artist making a charitable donation, you are thereby allowed to write off the value of your supplies only. Guess what? As an artist, you’re allowed to write off the value of your supplies on everything you create. The result of that law is that you do not benefit financially at all for donated work. There are, however, ways around this.

I figured out early on that while the organizations mean well, the fundraisers don’t typically understand the value of art. Most likely, they’ll ask you for a piece that they can then auction off. Most are not concerned with maximizing the money each particular piece brings. I’ve seen auctions where a more valuable original piece brought in less than a $10 print because neither the buyers nor sellers fully understood what was being sold.

This does not bode well for keeping your collectors happy, you happy, nor does it maximize the impact your work has on that charity.

As an example, a collector who paid $4,000 for a sculpture won’t be pleased if another of your original sculptures brings in $500 at a charity auction. The value of both your work and the piece your collector owns can suffer.

Set a Reserve or Sell It Yourself

The easy way around this is to come to an agreement with the fundraiser so it has skin in the game as well. Maria Brophy has a contract with guidelines to ensure this, and the charity must sign it before receiving any art. Basically, the art will have a reserve, and proceeds of the work will be split 50/50 between the Brophys and the organization. If the art does not meet the reserve, the charity must return the work. This contract gives the charity an incentive to get as much money as possible, as opposed to so many auctions where the fundraiser is happy with any money. The reserve also insulates your work from artificial deflation, which keeps the folks who collect and value your work pleased.

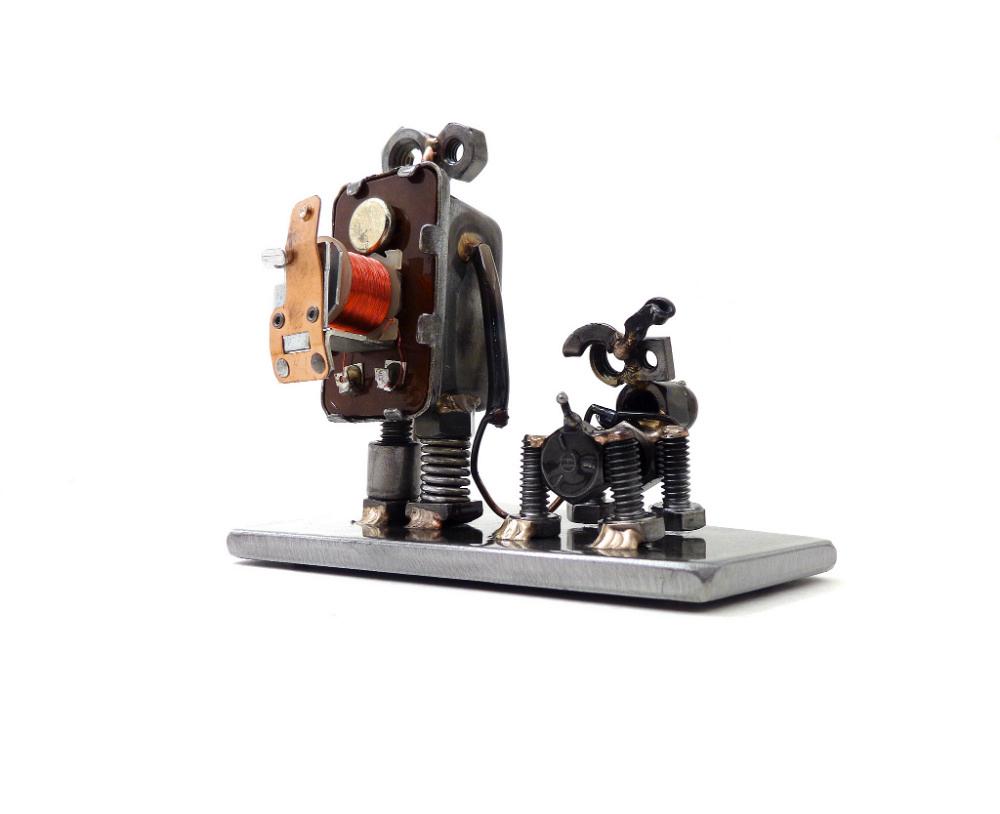

Another option, the one I most often employ, is to sell the work outright myself and give the entire amount from that sale to a charity I help support. Home Furever is a local no-kill dog shelter from which Darla and I adopted both “The Brown Dog” Woodson and our girl April. Every year, through Brown Dog Welding, we give at least 10 percent of our proceeds to the charity. Usually I’m able to donate a sculpture to its yearly fundraiser as well.

A few years ago, the time came when the value of my work increased and I started asking for a reserve. When the piece “Oldest Trick in the Book” failed to meet its reserve, the shelter suggested perhaps I’d have better luck selling it myself. Through social media, I have a larger reach than that singular event could give me. I was able to sell it through my website, and I gave the entire amount to Home Furever. At this point I was able to write off the sum of that donation. If the shelter had sold it, I couldn’t have written off anything more than if I hadn’t donated at all.

To be honest, I don’t donate work to get the write-off. It definitely helps come tax time, but the reason Darla and I donate is to help causes we believe in. The fact is, however, we all need to make a living, and saying “yes” with no strings every time a charity asks would require you to fully devote your energies into gifts. That’s not a sustainable business model. It’s good to know the rules, the laws, and that there’s an approach you can take that not only benefits you, but increases the impact of what you give.

All sculptures created by and images courtesy of Josh Welton, Brown Dog Welding.

subscribe now

The Welder, formerly known as Practical Welding Today, is a showcase of the real people who make the products we use and work with every day. This magazine has served the welding community in North America well for more than 20 years.

start your free subscriptionAbout the Author

About the Publication

- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Sheffield Forgemasters makes global leap in welding technology

ESAB unveils Texas facility renovation

Engine-driven welding machines include integrated air compressors

The impact of sine and square waves in aluminum AC welding, Part I

Compact weld camera monitors TIG, plasma processes

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI