Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

The diverse process portfolio from one full-service contract manufacturer

From stamping to fabricating to laminate panels and everything in between: The virtuous cycle of Acro Industries

- By Tim Heston

- October 4, 2019

- Article

- Assembly and Joining

Based in Rochester, N.Y., Acro Industries could have stayed a small tool and die shop, growing on work from local corporate giants Kodak, Xerox, and Bausch & Lomb, along with a variety of companies throughout the Northeast. That said, those three Rochester corporations are very different from what they were in the 1970s. If Acro stayed the same it might not have survived, or at least grown to the 150-plus-employee company it is today.

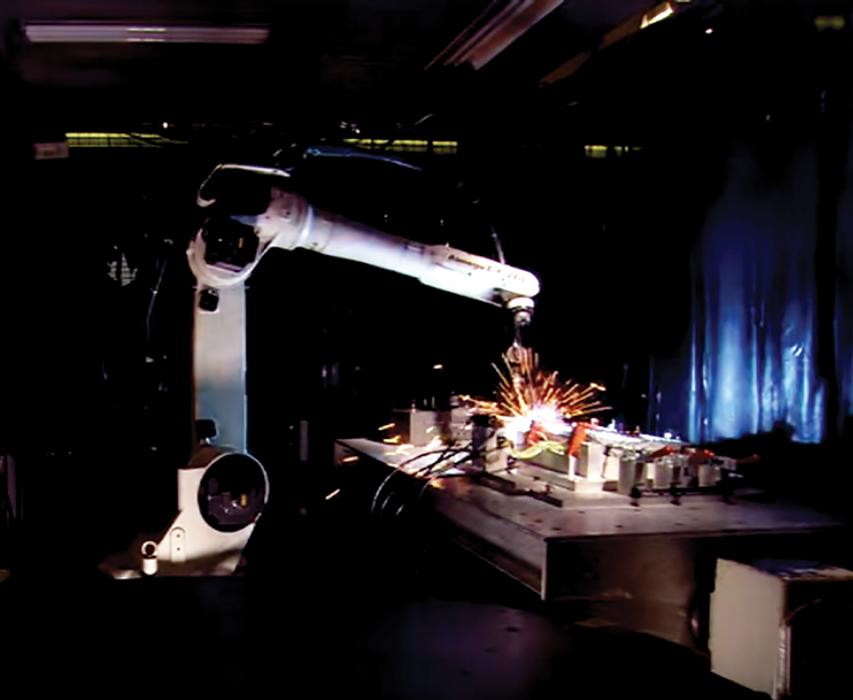

If you walk into a shop and see stamping, fabricating, welding, and machining, you can often guess the backstory. A tool and die shop with machining expertise added stamping (or vice versa), which then added metal fabrication equipment like laser/punch machines and press brakes to tackle high-mix, low-volume work.

But if you walk into Acro’s plant, besides all of that you’d also see a comprehensive assembly operation as well as an area with odd-shaped presses using special adhesives to bond a honeycomb structure between two aluminum skins. That backstory isn’t so easy to guess.

Process Diversification

What makes a shop stand out from the crowd? In the short term it’s price, of course, though if the shop can’t maintain quality and delivery at a certain low price, it doesn’t stand out for long. Over the long term, the people make a shop unique, including the culture they create and the delivery excellence they maintain.

All this creates trust, which (ideally) builds over time. Of course, you can’t see or feel “trust.” And though trust is an integral piece of the puzzle, you can’t measure it objectively.

Customers and prospects do see a shop’s process mix, however, and for the right customer, the process mix helps the shop stand out immediately. But it’s difficult for a shop to make a big leap into a new technology without customer commitment and trust, which come from delivery excellence built over time. The trust brings opportunity to alter the process mix, which attracts new customers, who build trust over time, which in turn leads to further opportunities to broaden the process mix.

It’s a virtuous cycle that has helped Acro evolve. The company looks nothing like the tool and die shop it was in the early 1970s. As Bill Kettle, business development manager, explained, “We have three core competencies—sheet metal fabrication, custom metal stampings, and laminate panels—and the first two can feed into our electromechanical assembly operation.”

Three of those areas—fabrication, stamping, assembly—aren’t unusual, but add the fourth, laminate panels, and the process mix becomes a real competitive advantage.

The Laminate Market

About a decade ago the company received a few projects that called for several sheet metal components as well as laminate panels. The shop initially outsourced the laminate process, and the panels would arrive at Acro for final assembly.

“We saw a lot of poor quality in the lamination, with very bad tolerances,” recalled Duane Olin, technical designer. “Because of that, we basically put a plan together to determine how much money we could save our customers by getting into this business. And we worked in tandem with our customers. At that point they wanted us to take over the whole operation, because they felt we could do a better job than the existing subcontractor.”

From this sprang Acro’s growing lamination capabilities. A decade ago the lamination department started with a single router and a single press. Now it has three different presses and three routers, complemented by a host of peripheral machinery, including bond-testing and peel-testing equipment.

There’s more to the story, of course. Before even jumping into the opportunity, Acro had to have enough trust with its existing customers to take the leap—and considering how Acro was stepping outside its metal forming and fabrication sandbox, it was a significant leap.

“It took more than just buying the capital equipment,” Olin said. “There was a learning curve. It was about developing the process, about learning how to bond adhesives under cold and heated pressure, so that we could provide a higher-level assembly that combined both the sheet metal and the laminate panels together. We developed our own best practices, and over time the process has helped us expand our customer base to pretty much everyone in the rail industry,” Kettle said.

Here, business development entered the picture. Being such a big leap, training and investment in the laminate process wouldn’t have made business sense for only a handful of target customers, no matter how large those particular customers might be. But after studying the market, Acro managers saw potential.

Where is this potential, exactly? Anyone who uses passenger rail sees it every day. “You see these in the interiors of railcars, the ceiling panels, the wall panels, curved doors, and the interiors of the cab,” Kettle said. “This includes trains, subway cars, and light rail, people-movers in airports. And we also do curved panels.”

Customer diversification in lamination is especially critical because of the nature of the work. It’s project-based, and for mass transit, the work often comes and goes depending on government funding. Revenue opportunities are there, but they’re inconsistent. If Acro simply grew its laminate business on the back of a few large clients, from a revenue perspective it would have been quite the roller coaster.

Thankfully, lamination isn’t limited to the rail arena. Laminate paneling can be seen in a surprising number of areas, from recreational vehicles to cruise ships to military ships and vehicles. It’s seen on many products, like electrical boxes, used across various industries.

The panels can be integral in the humanitarian and emergency-response arenas too. Linked together with hinges, the panels create structures, like washrooms or temporary offices, that can be transported, built, and disassembled quickly. The honeycomb inside these panels can surround plumbing and electrical modules, effectively creating an entirely functional temporary structure that could unfold and click together very quickly.

Laminate Panel Production

Essentially, the thin material reduces weight, the honeycomb adds structural stiffness, and the finishing options satisfy a range of cosmetic requirements. Deceivingly simple, a laminate panel consists of two thin sheets, which could be a metal or a nonmetal (like aluminum, stainless, wood, or, of course, laminate) sandwiching a honeycomb structure in between, which again can be made of a metal like thin aluminum or a nonmetal like a foam or composite. The exterior sheets, or skins, bond to the honeycomb with an adhesive.

The perimeter and surface features then are machined on a router to meet specified dimensional tolerances. Acro sources the honeycomb from a supplier, along with the skins. The final laminate could be various thicknesses, from a fraction of an inch to several inches, depending on design requirements and what works best for the core honeycomb material.

The bonding operation itself can vary with the application and the adhesives used. Adhesive itself could be liquid- or film-based, or a “solid” adhesive with higher viscosity. The bonding can occur at room temperature (cold bonding with a cold laminating press) or heated (thermal set bonding with a heat press) to varying temperatures, and the presses used apply pressure at different durations. Curing times vary, as do the cycle times of the presses themselves.

“It’s a broad range,” Olin said. “The cycle time could be five minutes or it could be two hours.”

It really is a “pressing” operation for adhesive bonding, not a stamping operation for forming, and adhesives require time to do their work. Thermal bonding cycle time hinges on the heating characteristics of the process and how that heat interacts with the adhesive material. Cold bonding depends more on the adhesion time for a particular adhesive.

The process combines elements of fabricating, machining, and assembly, along with a big dose of adhesive bonding. First comes the “rough cutting” of both the skin and interior honeycomb to the appropriate size.

The materials are bonded and formed on a laminate press, with tools to produce either a flat or curved panel. Even for curved laminate panels, the tools don’t apply forming pressure; the skins themselves are usually thin and ductile enough to conform to a curved contour. In these cases, the panels and honeycomb structures are bonded and prefixtured in a curved shape. That fixture holding the curved shape then goes into the laminating press. The press tools used generally match the laminate curvature, “but there’s a lot more to it,” Olin said. “We’ve built up the knowledge in-house to perfect it over the years.”

The panel then moves to the router for final machining to specified, and often very tight, tolerances. This is where the company’s machining expertise comes into play. “It’s not uncommon to have holes within ±0.005 inch,” Olin said. (Kettle added that Acro often gets involved with customers early in the design phase to address tolerance requirements. The shop can produce to within very tight tolerances, but if tolerances don’t need to be so tight, why not loosen them to decrease manufacturing costs?) After the size and features are machined, the laminate might have inserts or latch trims added, hinges for doors (common for electrical panels), and the skins might be painted.

“There really are so many different flavors and styles,” Olin said, “and we’re still adding them.”

Evolution in Assembly

Two decades ago a group of 20 Xerox engineers sat down with Acro engineers and brainstormed about a component called a copier transport, an electromechanical assembly that transports paper through a commercial imaging system for printing companies. The paper traveling through these transports took a serpentine path that’s about 15 feet long, passes under imaging components, and then is stacked automatically. These were not small, simple assemblies.

The meeting happened early, before most prototyping had taken place. Manufacturability discussions occurred from the get-go, considering material types and design unitization—that is, replacing many parts with fewer parts, or even just one part. The meetings also included error-proofing, ensuring a part can’t be formed or assembled incorrectly or in the wrong orientation. (This process has evolved to become what Acro calls the QPR, or the quality product review, before it launches a part program.)

Acro began fabricating individual parts for the transport on its lasers and press brakes and sourcing other parts as necessary. Before long it started assembling transports for one machine here, another machine there, 10 machines, 20 machines, and finally up into a production assembly, just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing environment, complete with product testing and returnable carts designated for specific transport system demands.

“We shipped more than 15 different models. Xerox gave us a monthly window [of planned demand], a weekly schedule, and a notice of daily demand, which we shipped to them,” said Ed Gaesser, program manager. “This comprised more than 2,000 parts, between fabricated parts we manufactured as well as numerous parts we procured.” These included various belt and gear drives and plastic components.

This wasn’t Acro’s first foray into assembly, but it certainly expanded the assembly operations far beyond what they had been before. As Gaesser explained, “From a procurement perspective, at the time we already had years of experience procuring outside items, so the learning curve was short.”

The trick was ordering enough components to meet demand, yet not so much as to be buried in purchased parts inventory—a real possibility, considering the number of purchased components and the variety of transports required. But over time the company perfected its use of kanban, establishing appropriate safety stock level and replenishment points, marked by clear lines on the numerous blue and yellow part bins throughout the assembly area.

Like many modern assembly operations, Acro deals with the complexities of high product mixes and customizations. Across the 15 models Acro produced, only a handful made up almost 70 percent of the total volume—the “high runners.” About 30 percent of the volume came from the remaining models.

Each workstation worked on multiple transports, and the mix of models changed with demand. Stations had bins full of common components that fit on every transport, no matter the configuration. But they also had other parts needed (dubbed “uniques”) staged on carts to meet a particular day’s demand.

“All this was set up in a way such that our assemblers had very little in the way of setup to meet the needs of a JIT environment,” Gaesser said.

Planners worked with Xerox to balance demand and efficiency. If assemblers could work on a batch of identical transport models at once, throughput could increase. Often it was just a matter of a representative from Acro calling Xerox to see if it had a number of replenishment carts to return—if so, Acro could increase throughput. That said, assembly workstations were set up to process various models over a single shift.

Next Steps

Both Gaesser and Kettle spoke in the past tense when talking about the Xerox assembly operation, and for a good reason: The product is nearing the end of its life cycle, and assembly is transitioning from production parts to aftermarket parts.

“It’s been a good 20-year run,” Gaesser said, adding that the company is working to fill the assembly capacity within the coming year, and as in the past, the unusual process mix, including lamination, is helping it stand out.

Like every contract manufacturer, it’s looking to add value by taking on more manufacturing steps and, ultimately, making life easier for the customer. For instance, Acro has performed many projects that called for sheet metal fabrication, welding, machining, and lamination. It’s the so-called “value-add” coveted by fabricators everywhere.

There’s a more concrete reason for turnkey services, though, as Kettle explained: “Customers are always trying to get the best price, but then you look at all the markups in the supply chain.” Every link has a price markup.

In this sense, the quest for cost reduction involves a quest for a turnkey operation that reduces the number of markups, lowering the direct overall cost and the indirect costs that come from managing a complex, multilayered supply chain.

Although its process mix is unusual, Acro’s overarching growth strategy isn’t: The more complementary processes and services Acro can offer, the greater potential efficiencies there are, and as a contract manufacturer, the more competitive it can be.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI