Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

How job shops can prevent a cash constraint during coronavirus pandemic

In a crisis, good money management ushers in opportunities for manufacturers and fabricators

- By Tim Heston

- April 27, 2020

- Article

- Shop Management

I recall visiting a FABTECH session in 2008 on operational improvement presented by the late Dick Kallage, former columnist for this magazine. He drew a line with two end points, one labeled “cash out” and the other “cash in”—the cash-to-cash cycle. It’s the time between financing an order (paying for materials and outside services) and getting paid for it. Put another way, it’s the time between spending cash for a job and getting it back.

“We need to shorten that,” he said in that gruff, no-nonsense tone he was known for after decades consulting fabricators across the industry. His point: Shorten the cash-to-cash cycle and a job shop’s cash position improves tremendously.

That sums up what a lot of operational improvement is about. For a good many of its 50 years of publication, The FABRICATOR has covered various improvement methods: lean manufacturing, quick-response manufacturing, theory of constraints, and others. They tackle problems differently, but they all aim to shorten the line—the time between “cash out” and “cash in”—that Kallage pointed to at FABTECH all those years ago.

It all certainly applies today. With the COVID-19 crisis, the industry faces huge challenges that run the gamut. Some shops are simply shut down, perhaps because they don’t serve what government officials deem as “essential” supply chains (even though sometimes they actually do). Perhaps work orders have fallen off a cliff. Or perhaps the order level has never been higher, which is a situation some fabricators face serving medical, food, beverage, and other supply chains running full out under the current crisis.

As the saying goes, you can’t make payroll with inventory. Cash is always king, but especially now. Struggling fabricators can tap into lines of credit, of course, but having ample cash in the first place can be a game-changer during a crisis.

To that end, The FABRICATOR reached out to Lisa Lang, PhD (known as Dr. Lisa), president of the consultancy Science of Business. She’s built her career around adapting the theory of constraints to the job shop. The improvement method moves the focus away from traditional efficiency measures toward managing overall productivity around identified constraints. She also advocates throughput accounting, which aims to give a better picture of a company’s cash situation. For a metal fabricator facing all the uncertainties of a pandemic, knowing its cash situation is a good place to start.

Throughput Accounting Basics

Throughput accounting defines costs differently than cost accounting, and doing so, Dr. Lisa said, helps paint a clear picture of a job shop’s cash situation. Instead of allocating expenses to assets, throughput accounting groups costs into two categories. The first involves costs that would be incurred whether or not a shop took an order. If a fabricator loses a bid for an order, it still needs to pay people, make loan payments on a new machine, pay office employee and manager salaries, and maintain equipment. Throughput accounting groups all this under operating expenses.

“If I sell one more unit of a product or service, these costs don’t change. “It’s not that these costs can’t change, but they don’t vary by ‘the one.’ They vary stepwise. If you triple your sales, they go to a new level. Your sales drops, your operating expenses drops to a new level.”

The second group of expenses are those that a shop would not incur if it didn’t take an order. These include material and outside services as well as sourced components, freight, and sales commissions. Throughput accounting calls these truly variable costs or totally variable costs (TVC). “These are the costs that vary by ‘the one,’” she explained. “If I sell one more of a product or service, then I will incur these costs.”

On the income side, throughput accounting defines sales the same way cost accounting does. But it also uses the term throughput, which in the context of the theory of constraints is essentially the cash that sales generate. It’s defined as sales minus TVC. To calculate profit, you start with sales and subtract TVC to get throughput. Subtract operating expenses from throughput and you get the remaining profit.

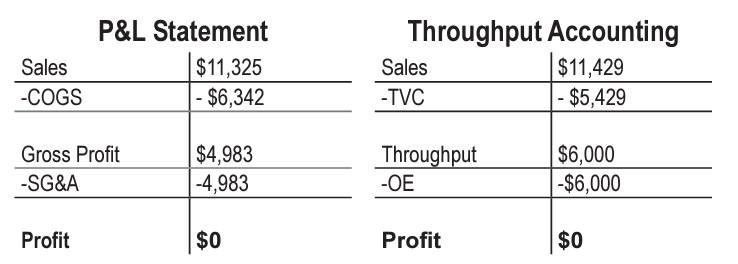

Figure 1 A conventional P&L statement subtracts cost of goods sold (COGS) from sales to get gross profit. The break-even point occurs when gross profit matches sales, general, and administrative (SG&A) costs. In throughput accounting, truly variable costs (TVC) are subtracted from sales to get throughput. As long as throughput matches operating expenses (OE) over a given period, a shop breaks even.

This method, Dr. Lisa said, presents a much more accurate picture of a job shop’s break-even point—a critical piece of information. Not knowing the true break-even point can get any operation into financial trouble in a hurry, especially if cash is tight.

This goes back to how break-even points are calculated. On a typical job shop P&L statement, sales, general, and administrative (SG&A) costs define the break-even point. If gross profit (sales minus costs of goods sold, or COGS) matches SG&A, the operation breaks even. Throughput accounting takes a different approach. To break even, throughput (sales minus TVC) must match operating expenses. Put another way, the money coming in (throughput) needs to match the money going out (operating expenses).

Consider the break-even numbers in Figure 1. To help illustrate the differences between cost accounting and throughput accounting, the financial details aren’t broken out; interest and applicable taxes are incorporated into the numbers, for instance. Regardless, the traditional P&L statement shows a lower break-even point ($4,983) than throughput accounting ($6,000). This is because of allocations like direct labor going into COGS; in throughput accounting, there are no allocations. COGS is higher than the TVC, which provides a lower sales number than is actually needed to break even. “There’s a big difference,” she said. “And these numbers are small. Add three zeros to these numbers and now we start to see the problem.”

Cash Velocity

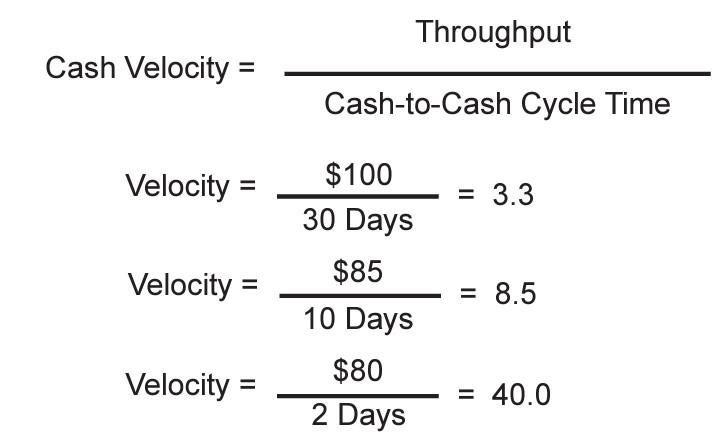

A third throughput accounting term is especially critical in a company undergoing a cash crunch. It’s cash velocity, which basically measures how long it takes for an operation to generate cash. It’s defined using two terms. First is throughput, which again in the context of the theory of constraints, is sales minus TVC. The second is the cash-to-cash cycle time.

Job lead times affect the cash-to-cash cycle time, of course, but that’s just one factor. Too many days in accounts receivable, especially when combined with too few days in accounts payable, prolongs the cycle. So can paying for material, services, and components long before the operation needs them.

Cash velocity, then, is throughput divided by the cash-to-cash cycle time (see Figure 2). The resulting number will depend on the job shop, the type of work it fabricates, and the customer mix it serves. Regardless, the higher the result, the greater the cash velocity. If the results trend upward over time, cash velocity is probably in good shape. But if it trends downward, cash velocity is slowing, which could mean trouble on the horizon.

Preventing a Cash Constraint

“If you track your cash velocity,” she said, “you can ensure cash does not become your constraint. And really, when you get into a situation where cash is your constraint, you’re pretty much out of business.” She added that this is why maintaining a clear picture of cash is so critical. “You need to prevent the constraint from happening in the first place.”

A shop in trouble might have orders, even sufficient capacity to deliver those orders, with vendors ready to deliver raw material. Unfortunately, vendors are no longer willing to supply material on credit.

“You then don’t have any cash to get the material you need,” she said, adding that by then, a shop can’t deliver on its promises, even though it might have a plethora of orders in the pipeline. Failure to make payroll follows, and the doors shutter not long after. However, if the shop had tracked its cash velocity and had known its true break-even point, the story might have ended very differently.

About Greater Velocity

Throughput accounting doesn’t replace cost accounting, which complies with the generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) that most entities in the financial world require, but the two can coexist. “Throughput accounting can be used alongside traditional GAAP accounting,” Dr. Lisa said. “The decision tools of throughput accounting can be used immediately, with no changes to existing accounting practices.”

Figure 2 Cash velocity is throughput (cash generated from sales) divided by the cash-to-cash cycle time. The numbers here reveal how, even if jobs generate more money (that is, a customer agrees to a higher price), the operation still could be headed for a cash crunch if it has low cash velocity. A job shop can be profitable on paper yet still run out of money.

And immediate information for decisions can be incredibly valuable, especially for capital-intensive businesses like metal fabrication. Cash continues to flow out not only to cover labor, but also consumables, expansive facilities, raw materials, and equipment payments. And if chaos reigns in the office and shop—if it takes forever to quote and prepare an order, and the order spends weeks on the floor, mostly as big piles of WIP—cash isn’t flowing into the business smoothly or predictably. All this highlights the need for predictable, quick work flow from the front office to the shipping dock.

The same is true for collections. A shop might fabricate and ship a product within hours, but if a customer uses a job shop as a bank and doesn’t pay its bills for weeks on end, the cash-to-cash cycle time can still be incredibly long. So what if the customer agrees to a high price? The job shop’s profitable on paper, but it still runs out of cash.

Dr. Lisa does offer strategies for getting out of a cash crunch, and some of them include aggressive deals that involve the promise of guaranteed quick delivery and quick payment terms. The deals might involve discounts to get customers’ attention, “but it’s not about price. It’s about delivery and payment terms,” she explained.

Moreover, the discounts need to be offered selectively and only on a short-term basis. “How you communicate these offers and to whom is key,” she said, adding that they shouldn’t be offered to companies that might expect a lower price forever.

Of course, making these offers are a last resort made with eyes wide open, knowing the shop’s true break-even point and cash flow situation. The ideal is to prevent a cash constraint in the first place. By continually monitoring operating expenses (the break-even point) and cash velocity, a job shop can put itself in a very favorable cash position.

The Storm Is Here

Considering the current crisis, a favorable cash position is a very good place to be. “This is not business as usual,” Dr Lisa said. “You might be fine and dandy, and then your shop gets shut down the next day because the governor announces you can’t have any more than 10 people gathered at any one time and place.”

She added that this is why cash flow management is so important now, tracking not only cash velocity, but also utilizing the 13-week cash flow model, where financial managers basically project the cash inflow and outflow over the next 13 weeks.

“Even if you think you have enough cash stashed away to weather the storm, make sure,” she explained. “Do the projection, evaluate the outcomes, and think through the possible scenarios. In early March the stores were full of inventory and airlines were making money. Today the shelves are empty, and the airlines are using runways as parking lots. We hope we bounce back fairly quickly after the battle with the virus is over, but hoping is not a plan.”

She added that job shops will likely see financial situations change dramatically in the coming weeks and months as customer mixes change. “Some customers might come back stronger than others,” she said. “Be prepared if your mix of business changes. Changes in the job mix can impact your operations and financial performance.”

The storm is here. Markets change daily. Countless businesses are in turmoil. It’s certainly not an environment for those averse to risk. But for the metal fabricator with cash, the opportunities could be tremendous.

Dr. Lisa Lang is president of Arizona-based Science of Business and author of “Increasing Cash Velocity,” available on scienceofbusiness.com. She works with jobs shops in her velocityschedulingsystem.com and jobshoppricing.com programs.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI