Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Auciello Iron Works revitalizes its structural metal fabrication shop

New England fabricator's experience exemplifies industry’s generational shift with technology and modernized workforce

- By Tim Heston

- December 17, 2021

- Article

- Punching and Other Holemaking

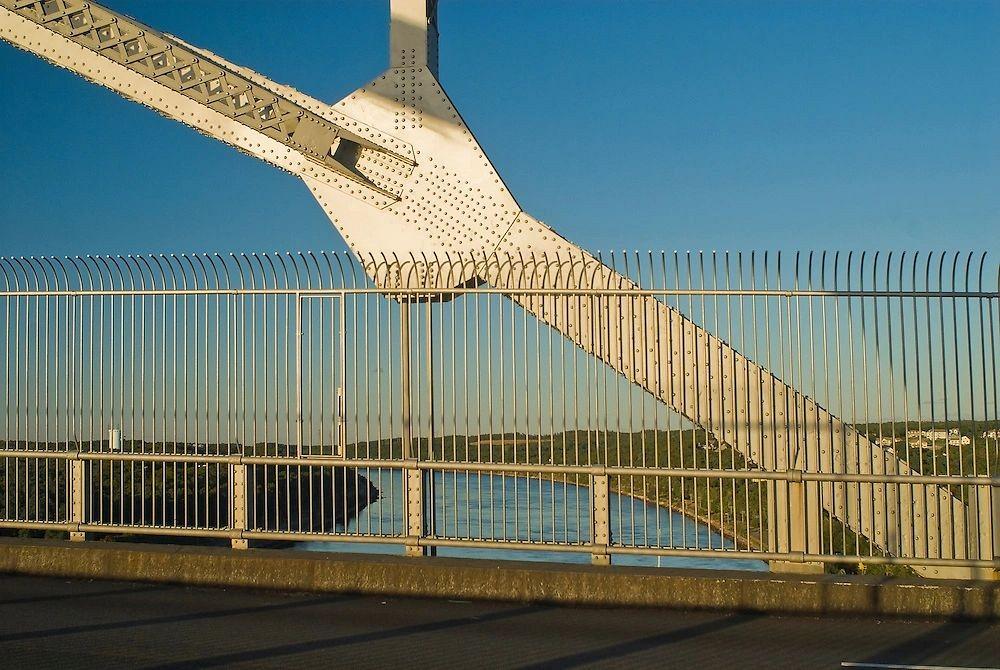

With key employees aging, Auciello Iron Works was like a dying church. Now the Hudson, Mass.-based bridge railing, structural, and miscellaneous fabrication shop is on a different, more sustainable path with new technology and modernized workforce. Image: Auciello Iron Works

Growing up outside Boston, Justin Auciello attended a church full of longtime members. Everyone knew everyone else. They enjoyed each other’s company and perhaps felt anchored by the place’s steadiness, its unchanging nature.

“The church only lasted until everyone passed away,” Auciello said. “It was a dying church.”

He didn’t want to see the same thing happen to his family’s business, Auciello Iron Works (AIW), a 20-employee bridge railing, structural, and miscellaneous metal fabricator in Hudson, Mass. Today, a decade after joining and three years since taking the helm, Auciello is leading a fab shop that, like so many in this business, has undergone a generational shift. With that shift comes new technology and new blood, including several new employees fresh out of trade school.

Still, one thing hasn’t changed since Auciello’s grandfather (also named Justin) started fabricating parts in 1932: the gradual transfer of knowledge from one generation to the next.

Not a Dying Church

“We are blessed with some great young people,” said Philippe Lefebvre, an expert welder who began at AIW 28 years ago and climbed the ranks from welder to quality control manager and, finally, shop superintendent.

Such long tenures show how deep the knowledge runs. They also show that, for the right person, AIW isn’t a bad place to work. Still, as Auciello found, long tenures also promote insular, because-we’ve-always-done-it-this-way thinking.

Joining the family business wasn’t always a given for Auciello. He graduated college with a journalism degree and wrote a bit for the Cape Cod Times while working shifts at a local restaurant.

“Eventually I got stuck in the restaurant business,” he said. “Time went by and I soon realized that it wasn’t an old man’s game. It’s tough to raise a family working late nights, holidays, and weekends.”

So he got his teaching certification and taught English and journalism to Cape Cod high schoolers. After about five years, Auciello and his family started talking. “We were looking to get off the Cape, and as we started to have that conversation, my dad and uncles started talking with each other too. They were getting older, and they didn’t have a succession plan in place.”

With that, the family moved back to central Massachusetts. AIW was now, officially, a three-generation family business.

Juan Morales (left) and Juan Jiminez—two younger employees hired out of trade school within the past two years— manage a workpiece after being processed in the profile drilling center. Image: Flex Machine Tools

Bad Reality TV

Full of drama, family businesses can be great source material for reality TV. AIW, alas, would be bad for television.

Justin Auciello’s father, Ralph, handled production; his uncle Tony managed contracts and engineering; and his uncle Mike handled sales. Being the oldest brother, Mike had the title of president, but he shared decision-making with his two brothers. The three comprised a collaborative leadership team, and each genuinely enjoyed each other’s company. They’d vote on key matters, and they of course had their disagreements. But because there were three of them, there was never a stalemate.

“They just liked spending time together,” Auciello said. “That’s how I saw it when I got here in 2010. They loved estimating jobs and pushing those jobs through the shop together. They really didn’t think about growing the business; they just wanted to keep it going.

“Each of them had his key area too,” he continued. “For me, it’s very different. I don’t have siblings or cousins I’m sharing this with, and I don’t have their knowledge, their lifelong understanding of the industry.”

Auciello didn’t grow up in the shop, nor did he ever intend to join the family business until those fateful conversations in 2010. But when he did finally join, he had several advantages. First, because the core employees, including Lefebvre, had been with the company so long, knowledge ran deep into the ranks. The company leadership anchored the organization’s positive culture, but they weren’t a driving force that pushed everyone to engage. Things wouldn’t fall apart after they retired.

This led to another advantage: Core employees liked their jobs. Indeed, long tenures mean something in a fragmented industry dominated by small shops that can have only so many chiefs. An ambitious employee wanting to move up the ranks might think of leaving. But when the culture is good and the work is enjoyable, people think twice before jumping ship.

An Office in a Time Capsule

Such stability, though, tends to create a kind of time capsule. So few key people coming and going can mean change comes slowly—a fact Auciello recalled even before joining the business. “I watched my dad cut an 11- by 17-in. drawing in half and fax it as two separate pages. He would literally cut and paste using scissors and tape.”

The company had only one organization-wide email (using a URL that didn’t even mention the company name) and no website. So, even before arriving in late 2010, Auciello began bringing certain aspects of AIW in the 21st century. “I found a web designer and put information together for a website. And I set up an email plan and gave everyone their own email address. By the time I walked in the door here, everyone had their own email address, whether or not they were going to use it.”

For his next project, he tackled the mountains and mountains of paper. “The paper around this place was just crazy,” he said. “There were stacks everywhere. We had drawings in drawers, and cabinets upon cabinets of job folders.

“So we scanned anything that was standard, or thought we’d need in the future. We did go back a few years [worth of jobs]. We do have some old material in the yard, and we wanted to be able to pull the certs on those. And over the past few years, we had two or three massive recycling trucks take away papers and office equipment like printers and scanners.”

FlexCNC’s FlexBeam machine eliminates the need for workers to lay out the hole locations manually, drawing information from the STEP file exported directly from CAD. What used to take hours now takes minutes. Image: Flex Machine Tools

Shop floor workflow isn’t paperless. Job travelers often have large blueprints for workers to fold out. Sure, Auciello could give everyone an iPad and have everyone pinch-to-zoom each and every drawing, but that adds unnecessary complexity. But today, the front office is a different world: no rows of filing cabinets, no mountains of paper.

A New Approach to Quoting

Office modernization helped accelerate workflows, but it didn’t help with the market changes Auciello began to see. Gradually but all too steadily, AIW was winning less work. The shop’s longtime reputation kept work coming in the door, but Auciello could see the writing on the wall: If something didn’t change, AIW eventually would succumb to the same fate as the dying church of his youth.

The company needed to win more bids. To do that first required changes to the company’s estimating processes. Historically AIW’s estimating involved getting price quotes for every component on a job, down to individual bolts and other hardware.

“Overhead is a big challenge in our niche of fabrication,” Auciello said. “Our competitors have very few people in their office. We can’t spend a million years estimating, so we need to be able to quote and draw quickly.” Any money saved by quoting costs down to the penny is quickly spent with all the indirect labor such tedious estimating requires. “We just can’t have a big office overhead. That just kills our estimate.”

A Technology Upgrade

Accelerated quoting solved only half the problem, though. Blanketing a market with bids isn’t very effective when they aren’t competitive. For many jobs, AIW’s price, even with the low overhead of a streamlined office, was just too high.

Part of this had to do with the changing requirements of bridge railings. AIW fabricates a variety of structural components and pedestrian handrailing. That said, bridge railings still make up the lion’s share of company revenue. Crash-tested bridge railings involve dense assemblies of tubes, and their use has proliferated in recent years. These jobs call for more tubes and many, many more holes and slots in every fabricated assembly. Laying out and fabricating the old-school way just wasn’t competitive anymore.

“If you’re manually laying that stuff out, you can’t get the work,” Auciello said. “And we were putting a tape on everything. We’d pull a tape along, mark and ding where the hole was supposed to be, pull the tape again, mark the hole, ding. It was so labor-intensive and inefficient.”

Tubes can be 24 ft. or even longer, which complicated material handling. “We’d lift the tube up with a crane, put horses on it, lay it out, bring the mag drill over, drill it, then move the drill down to the next hole,” Auciello said. It was just crazy.”

To stay competitive, the company had to automate the process. So in December 2020 it worked with distributor Northeast Machinery Sales to purchase a CNC profile drilling center, Flex Machine Tool's FlexCNC’s FlexBeam. The machine eliminates the need for workers to lay out the hole locations manually, drawing information from the STEP file exported directly from CAD. What used to take hours now takes minutes.

Technology and Character

Auciello made an unusual comment for any fabricator these days. “We’re actually not looking for help. Everyone is looking for help everywhere. It’s crazy. We’re lucky that way.”

Part of the company’s third generation, Justin Auciello assumed the role of president in 2018. A photo of his dad and two brothers—the company’s second generation—is in the background. Image: Flex Machine Tools

He attributed this to several factors. First, because AIW does subcontract work for the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, the company never shut down during the pandemic. “Although there were disruptions and it was a chaotic period, everyone remained employed,” Auciello said. That meant AIW hasn’t needed to rehire—an extraordinarily difficult feat in 2021.

Second, AIW is no longer in danger of becoming a dying church. It made the technology investments to be more competitive, streamlined its quoting, and—perhaps most important—created a culture where the right new hires want to stay.

Not everyone wants to stay, of course. No matter what AIW does, the company can’t change the fact that metal fabrication isn’t for everybody. As Lefebvre recalled, “We hired a few kids several years ago, and they decided they wanted to pursue a different career. Working in a shop just wasn’t for them.”

As AIW’s leaders see it, that’s fine. Auciello himself wasn’t keen on metal fabrication as a youth. But then life happened and circumstances changed. The time was right.

As Lefebvre explained, “The kids we’ve hired over the past two years are just terrific. They aren’t afraid of technology.” He added that they also absorb what shop veterans teach them—about manual layout, calculating bend deductions for press brake work, and all the rest. “The best way to learn this trade is from someone who has been doing it for 20-plus years. We need to prepare them for whatever the shop will be in 20 years or more.”

Technology makes a shop competitive; knowledge transfer builds a culture where new hires want to stay. Today, fabricators need both to survive and thrive.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI