Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Cold forming meets roll forming

Unique process produces metal shapes that are unexpectedly roll formed

- By Tim Heston

- October 7, 2019

- Article

- Roll Forming

Companywide, Welser Profile has more than 90 roll forming lines and 700,000 pieces of modular tools.

“I won’t believe this is actually roll formed until you show me the flower.”

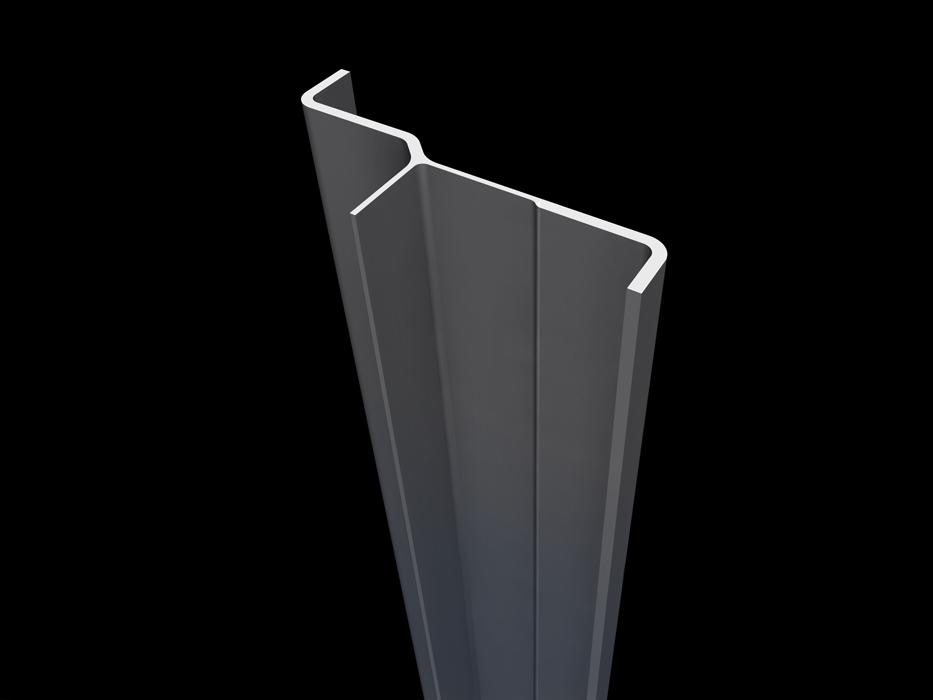

Bill Johnson, president and CEO of Welser Inc., the North American subsidiary of Austria-based Welser Profile GmbH, has heard this over and over from engineers during the past several years. He understands why people would ask. Usually he’s showing a roll formed profile that, for anyone who knows even an inkling about the process, doesn’t look roll formed at all. The part has sharp corners, edges at perfect 90-degree angles with no visible radius, and sheet sections that are noticeably thinner than other sections. They can’t imagine what the flower pattern, which shows the stages of forming after each station on a roll forming mill, would look like.In fact, the piece doesn’t look to be made of sheet metal at all. Some profiles have an array of notches or grooves, shapes that make the piece look like a hot forging or an extrusion—but it isn’t. It’s a profile created with a cold forming process that occurs on a roll forming mill, a technique that Welser Profile’s European operations have perfected and protected with patents in the U.S. and elsewhere. It applied for its first patent in 2007.

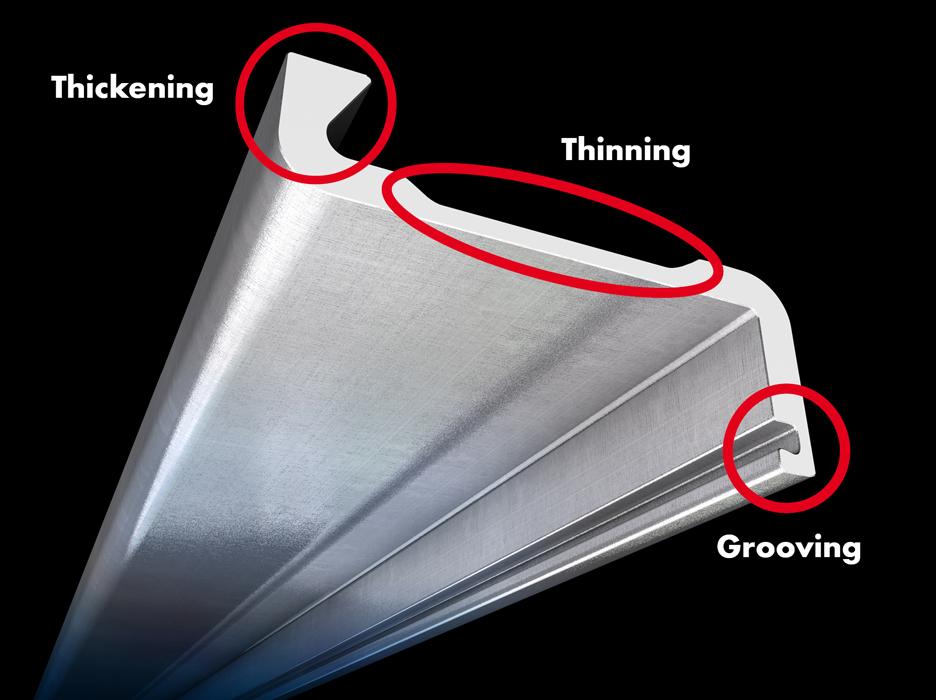

“Welser has patents on the thickening, thinning, and grooving of profiles through cold forming,” Johnson said. “It’s not machining, and it’s not hot forming. It’s something few if any in the U.S. have been doing or even tried.”

Because roll forming is such a mature technology, it’s not an area where many expect to see the unexpected. At FABTECH®, people smile and shake their heads as they watch incredibly powerful fiber lasers cut incredibly quickly, or an automated bending system correct for material inconsistency. They expect a surprise, considering all the advancements those fabrication technologies have undergone in recent years. They don’t expect to be surprised by roll forming. But as made evident by those “show me the flower” statements engineers have made, roll forming can still defy expectations.

Two Approaches to Lightweighting

In 2018 Welser made a significant move into the U.S. market with the purchase of Superior Roll Forming in Valley City, Ohio. The move was strategic, Johnson said, not only to increase Welser’s North American footprint, but also because Superior Roll Forming shares many of Welser’s cultural and strategic perspectives.

Both companies tackle specialized areas of the roll forming market that aren’t crowded with competitors. The two organizations also have worked to solve industry’s lightweighting demands. Parts need to do more, be stronger, and weigh less.

Superior has focused on the automotive space; Welser has had a focus on other industrial applications such as construction, agriculture, solar, and racking, though both companies serve a range of customers. Lightweighting in the automotive field has focused on high-strength material, and this has been Superior’s sweet spot. The relatively simple geometry of its roll formed profiles doesn’t raise eyebrows until engineers see the strength of the material that was roll formed. It’s not unusual for Superior’s engineers to develop part programs involving material with tensile strength of 1,400 and even 1,700 MPa. That’s almost 250 KSI. In Europe, Welser Profile engineers also meet the lightweighting challenge, but along with the use of high-strength materials they have also tackled the issue through complex forming.

Welser Profile’s patented process of cold forming works with lower-strength material, but the geometries that emerge from the roll form mill help reduce the weight of the overall assembly. The geometry might allow the profile to serve multiple functions and thereby reduce the number of parts (not to mention the dollars spent in production). For instance, a roll formed groove might create an interlocking joint that could eliminate welding or hardware. Or the profile’s shape might stiffen the overall structure. Perhaps most significant, Welser can create a profile thicker in some areas and thinner in other areas, providing strength where needed while reducing overall weight.

Breaking the Rules of Roll Forming

Those who engineer and design for conventional roll forming abide by decades-old manufacturability rules: Avoid tight radii, short legs, 90-degree bends, deep inside geometries, and more. “Of course, we form sharp 90s all the time,” Johnson said.

This profile, which looks like an extrusion, was in fact roll formed by Welser Profile’s cold forming process.

Engineers ask roll formers to break these manufacturability rules, of course, which is where a roll form shop’s tooling and engineering prowess come into play. The farther engineers can push the process—form a tighter 90, a deeper inside geometry—while minimizing tooling costs and process variability, the more competitive a roll former can be.

But as Johnson explained, cold forming on a roll form mill goes beyond this. The process produces part profiles that most engineers wouldn’t even think to roll form at all. “Picture a strip of sheet metal, perhaps 0.100 in. thick, that goes through a roll forming process. We can create a T-slot in the bottom center of that profile. Most people would say that can only be extruded. And if you needed it to be carbon steel, you’d have to hot roll it or machine it, depending on the tolerances and other part requirements. But we can easily roll form that geometry.”

Controlled Cold Forming

The details behind the process are proprietary, and Welser doesn’t publish the flower patterns. But Johnson does broadly describe several process fundamentals.

First, think of a coining operation on a stamping press. “While you’re compressing, you’re also stretching or shrinking. So you’re pulling material away and moving it to different areas of the tool [surface], like you’re filling out a radius on a tool. But [this cold forming process in roll forming] is like filling out a radius on steroids.”

Cold working does harden the material in areas, which can be engineered to the designer’s benefit. That said, the roll forming setup also has to take these material property changes into account. “You can see a considerable amount of work hardening, sometimes to the tune of a 30 percent increase,” Johnson said, adding that the increase needs to be engineered into the application from the get-go.

Even so, Welser Profile’s roll forming applications with cold working can incorporate secondary operations like piercing and welding. Like in conventional roll forming, piercing can occur before, during, or after the roll forming itself, but the tools used do need to accommodate the cold-working effects throughout the process.

The materials cold-formed at Welser Profile’s plants in Europe aren’t nearly as strong as the high-strength material being roll formed at the Superior plant in Ohio. The company cold-forms material up to about 450 MPa, depending on the application. But it takes more than choosing a material of a certain tensile strength.

“You can’t do this on high-strength, low-alloy material,” Johnson said, adding that “we often like to work with microalloy materials, which helps prevent fracturing. Obviously, the material selection is a big part of the process.”

To illustrate the process basics, Johnson described a telescoping tube project. One tube nests inside another tube and cannot rotate, so each tube has a ridged groove at specific positions around the circumference. These aren’t simply stiffening ribs with radii; that would result in some rotational play after one tube nested inside the other. These tight-tolerance tubes need to nest precisely and telescope smoothly, with little to no rotational play. Moreover, the OD of the outside tube has to be perfectly consistent, with no protrusions from a form placed on the ID. To that end, these tubes have actual grooves that at first glance look to be extruded, only they’re not. They’re cold-formed on a roll forming mill.

To create the grooves, roll tools thin the material at specific points along the tube circumference. Engineers design the process in such a way that they can precisely predict material flow, away from those “thinned” grooves and toward the rest of the tube circumference. The material flow has to be controlled precisely to create a consistent tube wall thickness in between those grooves. If the tube wall thickness isn’t consistent, the assembly won’t nest together as designed.

The cold forming process at Welser Profile’s European roll forming operations can thin certain sections, thicken others, and place grooves in other locations.

Again, glance at the part and an engineer might think it to be an extrusion or perhaps a hot forging, and herein lies the challenge shared by any manufacturing technology that defies conventional wisdom. Many engineers wouldn’t consider designing such a part, thinking it to be too costly or outright impossible to make. So Johnson and his team are spreading the word, not only about the process’s capability, but also about the virtues of having Welser Profile’s roll forming engineers take part in the early design stages of a project.

Design and roll engineers work together on the material choice, strategically choosing the thickness and the refined grain structure, driven in part by the tool section and where exactly the cold forming (that is, the thickening and thinning) takes place as the flower forms into a complete profile. It’s a puzzle much more complicated than just piecing together the modular sections of a roll tool (and Welser Profile uses modular tools almost exclusively).

11th Generation

With more than 2,500 employees and more than 90 roll forming lines, Welser is one of the world’s largest family-owned roll formers, employing a large percentage of the workforce in tooling production and engineers alone who work with a tooling library that over the years has roll formed more than 22,500 different profiles.

“We have more than 700,000 pieces of [modular] roll tooling in inventory right now,” Johnson said.

The company makes full use of in-house and off-the-shelf software. “I believe we’re one of the largest COPRA [roll form software] users in the world,” Johnson said. He added that the company builds some of its roll forming lines from the ground up, then works with machine builders for the rest. In fact, the company asks many machine builders to include certain adjustments that are far from a conventional request.“The roll form machine builders don’t know why we ask for certain specifications, but they oblige us,” Johnson said, adding those “unusual adjustments” in the rolling mill have helped Welser refine its cold forming process.

So how long has Welser been in the metals industry? Johnson chuckled. “Oh, just about the whole time.” He was only partly joking. The company traces its founding back to 1664. “And in all seriousness, the company has been in the steel industry the entire time. It started out in foundries, and in the late 1950s started roll forming sheet products, and it has evolved ever since.”

The Welser family has owned the business for 11 generations. “The CEO is Thomas Welser,” Johnson said. “His grandfather started the roll forming focus at the company, and his father was really the entrepreneur who grew the size and scope of the business.” Today, global annual revenue is more than US$700 million.

Johnson continued, “And while Thomas’ father built the company in Europe, Thomas has become really involved in international sales and business development. He felt it was his generation and his time to take the company global.”

Acquiring Superior was one part of that strategy; introducing cold-form roll forming technology to the U.S. was another part. At this writing, the cold forming process occurs in Welser Profile’s European operations, from which the company exports to the world market. No plans have been announced to bring the technology stateside, at least not yet. Like anything else, Johnson said, the roll former plans to expand capacity as demand dictates.

A flower pattern of a conventional roll form profile shows the forming stages as material passes through the roll stations. Because the details behind Welser Profile’s cold forming process are proprietary, it doesn’t publish the flower patterns.

Welser Profile and its Superior subsidiary both offer conventional roll forming, but both tend to focus on areas that aren’t asking for the norm. For Superior, it’s high-strength material; at Welser Profile, it’s complicated forming that in many cases competes not with other roll formers but with extruders and other manufacturing specialties.

In fact, Johnson said his team is following the aluminum extruders playbook. “In the early 1980s aluminum companies came to the market and said, ‘If you can dream it, we can extrude it.’ They were very good at presenting options to engineers. If you just dream it up, then for a small tool charge, we’ll produce it. It took the restraints off engineers, because they really could draw just about anything. Now, we’re doing something similar—only now, it’s with roll forming.”

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI