President

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

3 rules for job shops to follow to avoid unprofitable work

Build a quote database to identify worthwhile RFQs, increase sales

- By Vincent Bozzone

- October 24, 2019

- Article

- Shop Management

A job shop that submits a quote for every request that comes in the door might keep its estimators busy, but with a lot of wasted effort. Getty Images

Job shops that quote every request that comes in the door are shooting themselves in the foot. Regarding this, a tooling engineer recently told me, “It took me 12 years to learn what you just said.”

It’s not an easy concept, and understandably so. It’s difficult for a job shop not to answer every request for quote (RFQ) because it doesn’t know when the next order will be won. Job shop owners and managers have that common fear of people being idle on the floor and expenses running aheaad of revenues. If a shop takes on unprofitable work, managers often say, “At least it pays the light bill.” Unfortunately, that rationale really doesn’t work, and building a quote database will make this abundantly clear.

Defining Unprofitable Work

Before you can deal with unprofitable jobs, you first need to define them. In a job shop, you deal with three types of unprofitable work:

Work that the shop can do. Your shop has the experience the job requires and you don’t anticipate any problems. You might not make a profit, but you won’t lose your shirt. This work will pay the light bill.

Work that is beyond the shop’s capabilities. You might not have the proper equipment or know-how, and you expect glitches, but you take the work anyway. This will not pay the light bill, and you can lose your shirt.

Work that the shop cannot deliver on time. If you add an order to a shop floor that is at maximum capacity, you create delays that will ripple through the operation. Something will have to give. You need to create or confirm capacity before you take an order, or you can wind up losing your shirt as customers find you to be unreliable.

Three Rules

To avoid unprofitable work, you need to follow three rules:

Differentiate between work that you can do for cost and work which seems to pose problems or difficulties. Do not quote problem work.

Create the required capacity before you accept a short lead-time order.

Do not quote orders you cannot deliver on time.

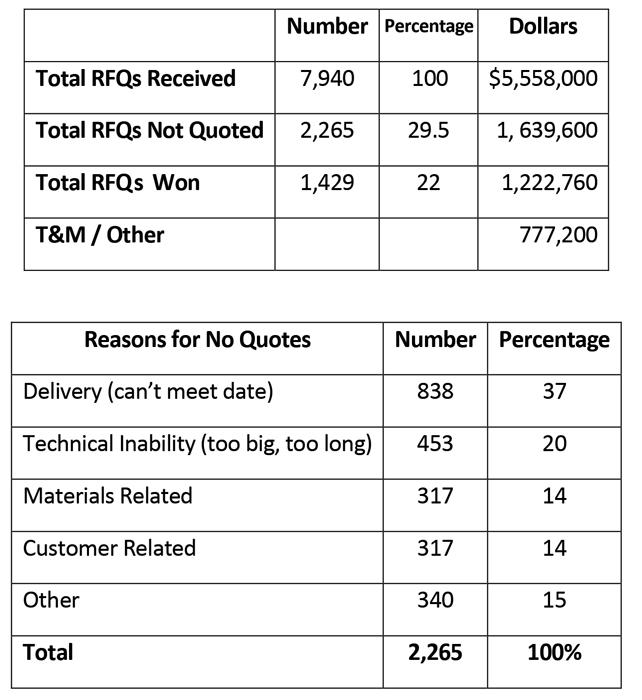

From this you can learn and improve operations based on your quoting history. To start, track your reasons for not quoting an order. Figure 1 shows a shop that decided not to quote almost a third of all RFQs it received. In fact, it chose to pass on more than $1.5 million by not quoting some 2,265 RFQs. At a 22 percent hit rate, this would be in the neighborhood of $360,000 in revenue.

The shop identified why it didn’t quote the work. The most common reason (37 percent of RFQs) was that it couldn’t meet the delivery date, followed by equipment limitations (20 percent). With the reasons identified, the shop now can consider potential actions to reduce the number of no-quotes in the future.

For example, the shop was not able to handle 453 quotes because of equipment limitations. Should they add another piece of equipment with added capability? Shop managers need to do a more detailed analysis of no-quotes in this area, but at least now they have information on how much business they could be losing. The same can be said for delivery, where managers chose not to quote 37 percent for $338,309.

This shop has a strict policy of not quoting orders it cannot deliver by a customer’s desired date. This avoids creating chaos on the floor as production struggles to produce orders that exceed the shop’s capacity. Remember the old adage, “Chaos on the floor means profits out the door.”

You may be thinking, “This is all well and good when a shop is full and can afford to turn down work.” But what you might not realize is this shop can afford to turn down work because it adopted these three rules a few years ago and tripled sales from a little over $800,000 to more than $2 million today. This has helped them to maintain a 98 percent on-time performance.

Meeting promised ship dates translates to reliability in your customers’ eyes, and this is an excellent reason for continuing to award work to your shop, even when your prices might be a bit higher than your competitors’. Reliability is a powerful competitive advantage.

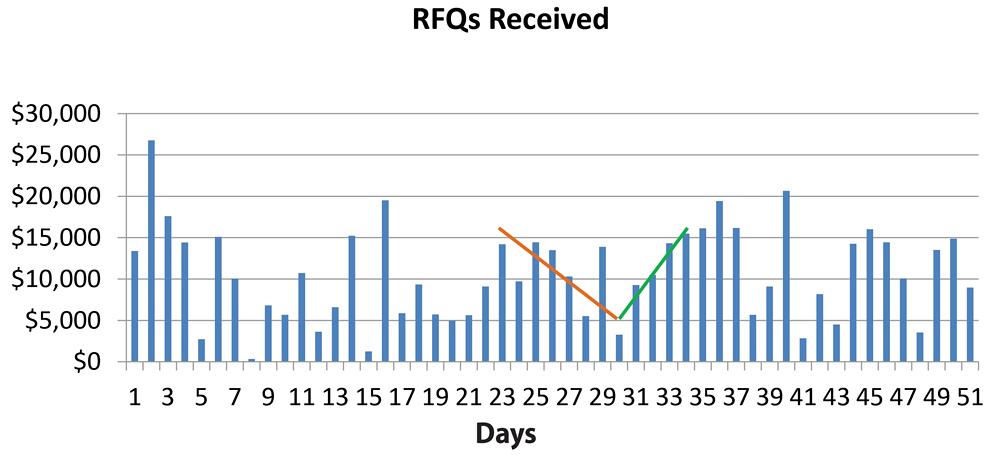

Even though demand in a job shop varies, having an idea of the pattern of RFQs that come to your shop can provide a valuable perspective when it comes to quoting and pricing. For instance, if you make it a habit to quote work at cost just to keep the shop busy, you can miss out on better margins.

Figure 2 shows the volume of RFQs coming into a shop. If you chase the downward short-term trend by reducing your price (orange line), you will fill your shop with unprofitable work when RFQs turn around and increase (green line). Again, don’t make a habit of quoting work with no margins.

Build a Quote Database

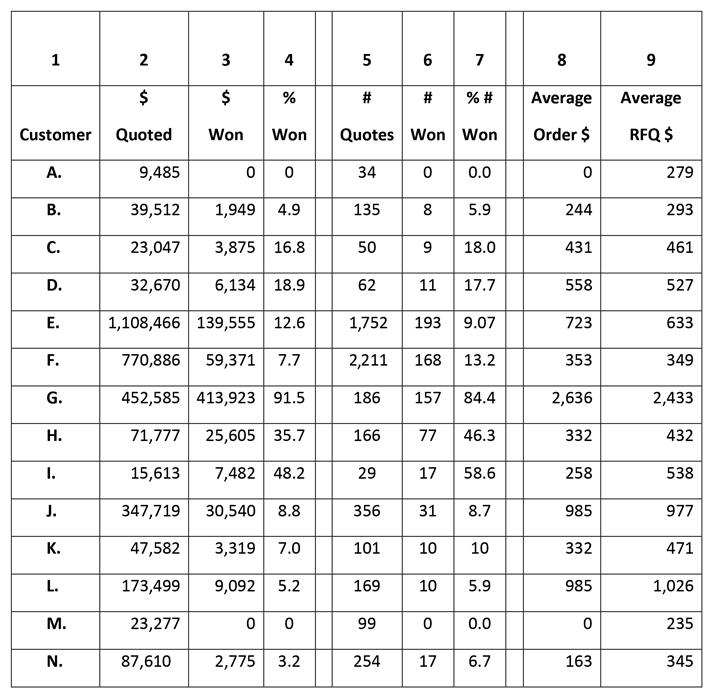

Tracking your no-quotes and the reasons behind them is just a start. You can mine so much more information from a quote database. Other data points include the customer; the amount quoted for each customer; the amount won; the percentage of dollars won (dollars won/dollars quoted); the number of quotes submitted; the number of quotes won; the percentage of quotes won; the average size of won orders; and the average size of RFQs from each customer.

Who did you win the most work from? Who awarded you no work? With whom do you win the largest orders? Where are you wasting time? Where do you achieve the highest hit rate? Analyze the quote database to see where you’re expending effort and where that effort produces results.

Figure 2

If you quote low during low demand (orange line), you end up filling the shop with unprofitable work just as demand starts to rise (green line).

Consider Figure 3, which gives just a taste of the kind of information you can glean from a quote database. And getting that information doesn’t require hours of analysis; it all comes at a quick glance.

Your Best Customers. Customer G is your biggest customer with the most dollars won and the largest order size; and if those orders are profitable and don’t wreak operational havoc, G is probably your best customer too. You’re also doing pretty well with customer I, winning half its business. Unfortunately, the amount is small. Customer H appears to be solid too; you’re winning a third of its business.

Accounts Worth Developing. Customer J might be a customer worth developing. You’re winning only 8.8 percent of the $348,000 submitted. This customer could be worth $76,000 at your average 22-percent win rate instead of the $30,500 you won. Its average order size is nearly $1,000, which has the potential for greater profitability.

Where Effort Might Outweigh Results. Right off the bat, you can see you’re wasting time with customer M, who has awarded you no business. And you can see where the low hit rates are, including customer F, which has a win rate of just 12.6 percent, slightly more than half your average win rate of 22 percent. You can do better at getting more business from this customer, and you need to find out how. If you won at your average 22 percent rate, you would have gained $244,000.

Customer E submitted the largest dollar volume of RFQs, but you had to submit almost 2,000 quotes to get that business—and you won only $139,555. Customer B is another case where the effort seems to outweigh the results. You submitted 135 quotes to win a measly $1,900 with a hit rate of only 4.9 percent.

Customer N is another high-effort, little-results customer. You submitted 254 quotes to win a paltry $2,775 out of $87,000 quoted. Your hit rate is 3.2 percent. You need to find out what you can do to increase that hit rate or decide if it’s even worth the effort.

Note that these observations do not account for other business you may be getting from these customers. For example, say a customer gives you a fair amount of time and materials (T&M) work, where you bill after the job based on actual labor and materials costs, rather than an estimate. In this case, it might make sense to answer the RFQs that customer sends. Other customers might provide additional work that is not reflected in the quote database numbers.

Most of this data is already in your main computer system; you just need to find a way to access and organize it so that it provides information. A separate profit analysis for each customer is well worth conducting.

Increase Sales

Once you build your quote database, you can use it to increase sales by recognizing where your effort is paying off and where it’s not. It also shows you where you can win more work from existing customers without resorting to cutting prices. You need to focus on customers with the greatest potential—that is, those with low hit rates, a high number of dollars quoted, and large order sizes—and a good quoting database can help you identify them.

Perhaps the greatest benefit is that a quoting database provides the basis for communication with customers. You can ask your customers how to increase your hit rates or why you are not winning the larger-dollar RFQs. This gives you the opportunity to make them more aware of the total package of services your shop offers, and how using it can make their business more successful. In these days of relationship selling, that’s a huge plus.

Vincent Bozzone is president of Delta Dynamics Inc., 248-961-1380, vincent.bozzone@gmail.com, jobshop360.com, deltadynamicsinc.com.

About the Author

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI