Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

A new look at the job shop organization chart

The structure should align with the job shop business process

- By Tim Heston

- March 4, 2019

- Article

- Shop Management

“Have you ever seen ‘Job Shop Management 101’ taught in any college or university? I’m betting not.”

So said Vincent Bozzone, president and founder of Delta Dynamics, a Michigan-based consultancy long known to many in the job shop world. Bozzone is the author of Speed to Market: Lean Manufacturing for Job Shops, a book focused on refining job shop operations to shorten lead time, the order-to-cash cycle. Still, Bozzone conceded that this and his other previously published works haven’t delved deeply into the job shop management structure.

“There is no ‘theory of job shops,’” Bozzone continued, adding that no one in academia or much of the management consulting world really has dissected the job shop business model in a serious way.

When you think about just how complex custom fabrication job shops truly are, it’s no wonder that many of them struggle with on-time delivery. For years the annual “Financial Ratios & Operational Benchmarking Survey” from the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association has reported on-time delivery rates in the mid-80 percent range. Sure, the annually reported average comes from a wide range of responses, and many fabricators do achieve near-perfect on-time delivery rates. But just as many report rates at or below average.

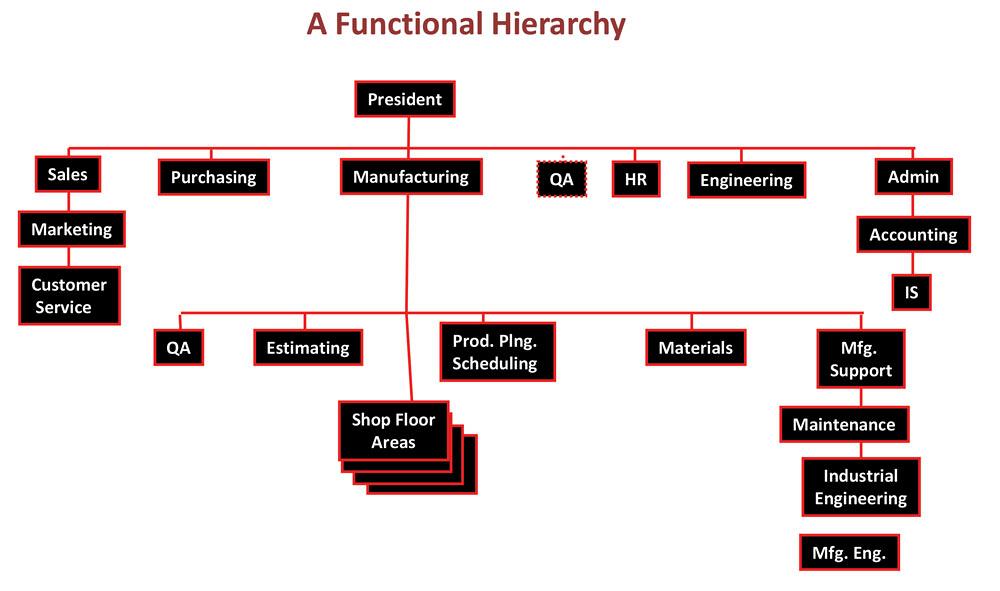

Many job shops grow into organizations that ship hundreds or thousands of different parts over a month or year, each with their own demand cycles, routings, and engineering and manufacturing requirements. It all creates a web of complexity—but why, exactly? Bozzone attributes at least some of that complexity to the way most job shops are organized: around function instead of the business process.

Switching to a process-based organization could be a good first step in real change. Changing the organization chart won’t eliminate all problems, Bozzone said, but it could help, rather than hinder, the flow of jobs through the business.

A Job Shop Growth Story

According to Bozzone, having an organization chart grouped by function is where those dreaded communication “silos” come from. Say a cutting department manager has a question about material purchasing practices, considering the issues he’s experienced on the cutting table. Strictly speaking, the organization chart says that he should speak to his supervisor, who then should speak to the manufacturing manager, who then should speak to the president. The president then talks to the purchasing manager (who, again, reports to the president, not manufacturing).

Communications might not be this formal, of course, particularly in the fast-paced job shop world. It doesn’t make sense for every tiny purchasing issue to be brought to the president’s attention, though major purchasing issues would be.

Of course, the real issue is that the cutting problem occurred during production, and it’s creating a speed bump. Flow stops, other jobs are delayed, and the dominoes fall.

To avoid these problems, many have trumpeted the benefits of “breaking down the silos.” Managers promote good communications, hold meetings to keep everyone in the loop, and more.

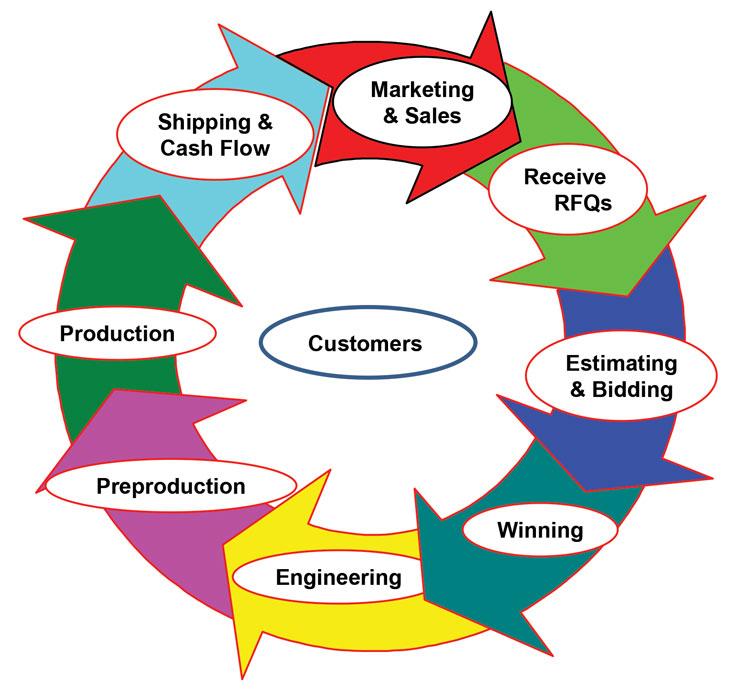

The job shop business process cycle starts with marketing and sales and ends with shipping and receiving payment for a job.

But Bozzone’s approach goes deeper and tackles the root cause: the organization structure itself. What’s wrong with it? As Bozzone explained, it doesn’t consider the actual business processes that define how a job shop actually works.

What are those business processes? Bozzone illustrates them in a cycle, starting with marketing and sales. “Marketing and sales generate a request for quotations, which are estimated and bid upon. The shop either wins them or loses them. Typically, you lose a lot more than you win.”

Once a job is won, some level of engineering can be involved,“anything from a couple of sketches to a full-blown engineering design effort.” Next comes preproduction, which prepares the job for production (more on this later); production; and finally shipping.

The Three Functions of the Order Cycle

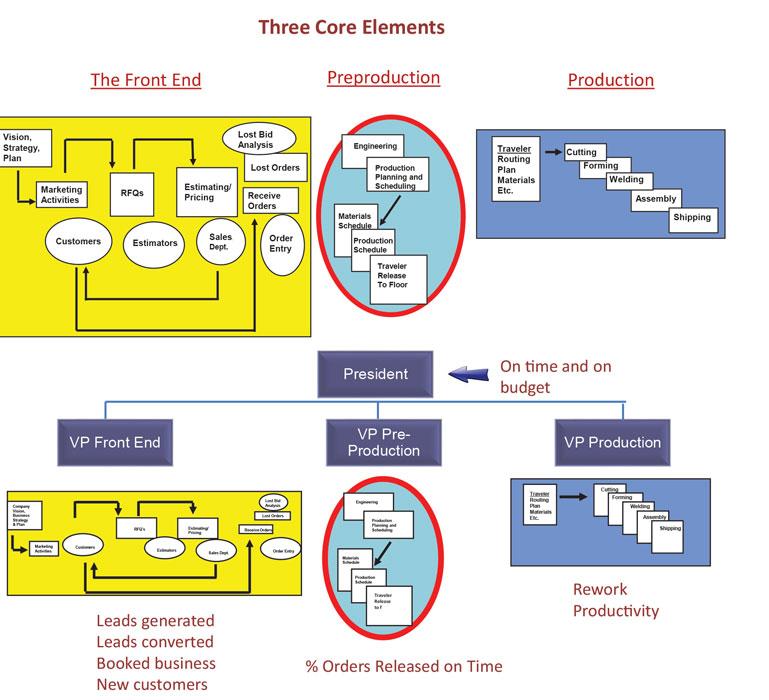

The whole quote-to-cash cycle really can be grouped into three basic functions: selling and bidding, preparing the won orders for production, and producing and shipping those orders. Bozzone calls these the front end, preproduction, and production, respectively. Supporting these three functions is an area Bozzone calls “management information, which incorporates finance, human resources, IT, and office operations.”

In the early stages of a job shop’s life, one person does the first three and at least some of the fourth (though functions like continuous improvement wouldn’t be formalized). Then the founder might hire someone—a sheet metal guru—to prepare jobs, do a little engineering, and run the machines (preproduction and production), but the founder still sells and bids on work and manages material purchases (front end), building those customer and supplier relationships that help the business grow.

But then the order volume grows, and the founder hires more and more people. Orders get more complicated, and the number of orders and machines grows. The shop hires engineers, estimators, and operators. Before you know it, the shop has a traditional functional structure—which, you might notice, has something missing.

The Need for Preproduction

“My bet is that most custom fab shops don’t have a designated preproduction department,” Bozzone said, “or even a way to control preproduction activities. Instead, the various preproduction tasks are scattered around the organization. This is a prime reason for long lead times.”

Preproduction—that process the technical guru took care of on his own when the shop was young—eventually becomes diluted. Engineers do a little preproduction work, prepping the CAD drawing so the part can be manufactured on the floor. Schedulers might put together a routing through certain machines to take advantage of available capacity.

But then parts are released to the floor, where the holdups inevitably surface: a press brake setup that just doesn’t work, a weld fixture that hasn’t been made, a powder coat that just won’t stick.

Some large fabricators designate a department for prototyping, one-offs, and low-volume nonrepeating work, where engineers and highly skilled machine operators and welders work together to make first articles and prepare a job. But the vast majority of shops do not have such a department, and a good many smaller operations don’t have the machines to spare.

According to Vincent Bozzone, a traditional functional structure does not align with a job shop’s business processes.

Bozzone’s “preproduction” concept focuses less on part design, which—besides design tweaks for manufacturability—is usually outside the job shop’s sandbox. It instead takes a broader approach and focuses on developing a production plan that includes purchasing and capacity planning, scheduling, programming, quality protocols, customer approvals, and developing necessary fixtures and tooling setups as well as effective routings. The idea is to make production as smooth as it can be.

He added that, yes, if a job shop needs to develop first articles and test parts, it’s ideal for a designated preproduction department to have its own machines, but it’s not entirely needed as long as machine time for preproduction is made available in the shop.

And preproduction doesn’t necessarily need to make first articles. In fact, for some job shop businesses, a first article would be impractical. Bozzone described Max Weiss Co., a job shop in Milwaukee he recently visited. The company bends and rolls massive beams, pipes, and angle for the construction business and OEMs.

Rolling cycle time is measured in hours, and one massive piece can cost serious money. In this case, he said, preproduction would entail the engineers and tooling professionals working together to ensure production goes smoothly, that the first roll goes as quickly and predictably as possible.

But again, many organization charts place preproduction roles in various areas. Purchasing and programming might be in the front office and report to top management. A quality assurance department could devote some of its time to preproduction (quality protocols), and some of its time to production, checking production parts to meet customer quality requirements.

A lead operator in the press brake department plays a preproduction role too, setting up jobs to make sure they run correctly. Only he or she is probably doing it after the job has been released to production. If that lead person runs into trouble developing a setup and spends hours trying to perfect it, the brake department just lost available capacity for other jobs.

Align Structure With Process

Yes, fabricators could work on developing communication among departments and foster an environment that encourages ownership over the quality of one’s work. Problem is, a job shop’s organizational structure often works against this.

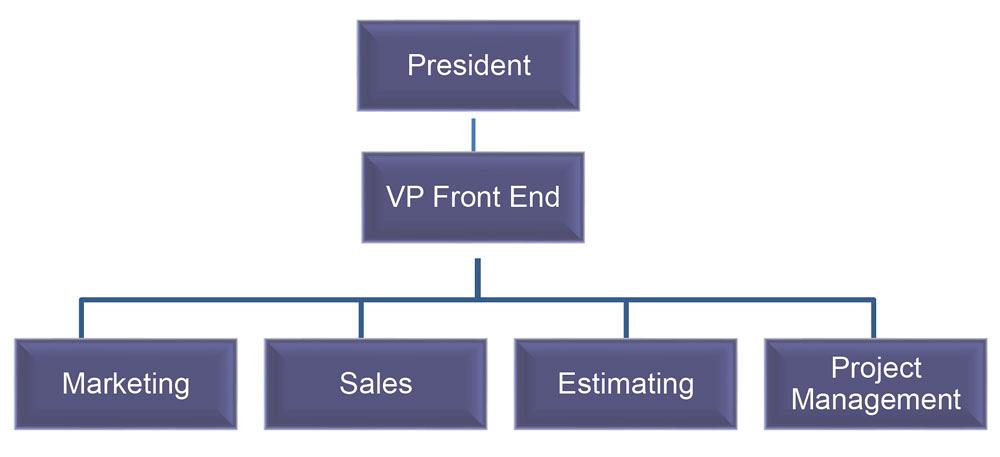

Bozzone’s proposed job shop structure aligns with the job shop business process. A shop could have vice presidents over the front-end processes, preproduction, and production, and then organize the related functions underneath.

The preproduction department could include engineering (which could include physical tryouts of difficult parts), production planning and scheduling, materials and production scheduling, quality protocols establishment, and traveler release, at which point the baton is handed off to the production department.

What about support functions like QA, manufacturing support, and maintenance? The exact organization depends on a job shop’s niche and product mix, Bozzone said; but wherever these support functions are placed, they should support, and not work against, the job shop business process.

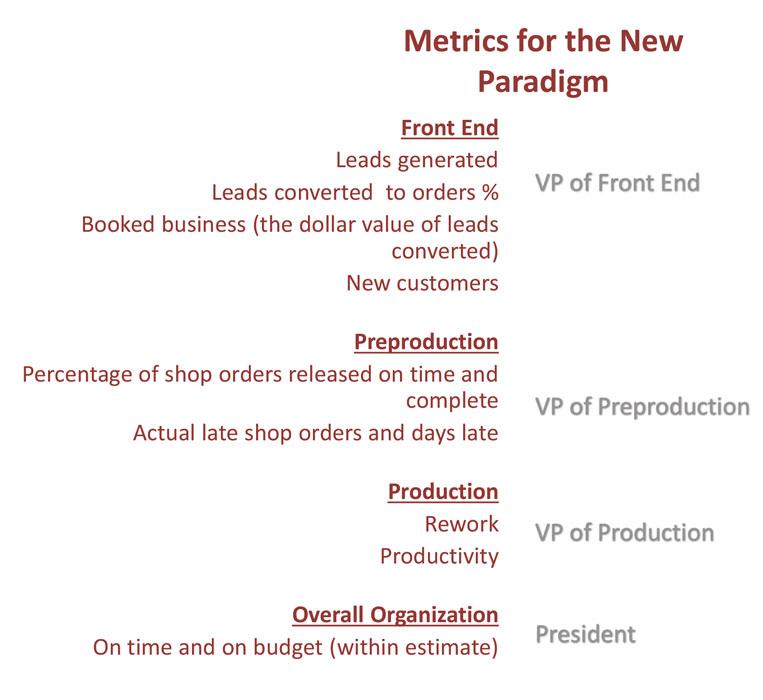

Bozzone proposes a new job shop structure, with front-end, preproduction, and production departments that align with the shop’s business processes. A separate administration, or “management information,” department—for functions like HR, finance, and IT—would also report to the president. The red text in the bottom chart indicates key metrics.

For example, some QA techs could be under production, ensuring inspections are made and documented per customer requirements and reporting to the VP of production. The preproduction department also could employ quality experts who develop the quality protocols for each job.

A similar arrangement could be made for maintenance functions. Most maintenance personnel would support production and, hence, report to the VP of production. Meanwhile, if preproduction has separate equipment for job tryouts, technicians within the preproduction department could be responsible for their own machine maintenance.

Still, Bozzone emphasized that such divisions should never foster “not my job” mentalities. If a maintenance expert in production knows best how to fix a press brake in the preproduction area, he should fix the machine. And he should have the incentive to do so, because the better preproduction does its job, the easier production’s job becomes. All this, Bozzone explained, is where performance metrics come into play.

The Right Metrics

Metrics and performance reviews would be based on satisfying demand for the next customer in the value chain. That is, they help make life easier for those downstream. This builds the foundation for cross-company communication and collaboration. Knowledge is shared. Decision-making occurs quickly. Production gives feedback to preproduction, which gives feedback to the front end. If you aren’t giving your customer (internal or external) what he or she needs, your performance suffers.

Those in the production department would be measured based on how well they meet the end customer’s demand. Are deliveries of quality parts made quickly, within the expected time? Are the dimensions and quantities correct?

“There’s an old job shop adage,” Bozzone said. “‘The longer a job sits on the floor, the more it costs to get it out the door.’”

Production performance metrics might include percentage of jobs that need rework, along with other productivity metrics like dollars shipped per hours worked.

“Rework is an important metric because it is the most expensive source of waste in any job shop,” Bozzone said. “Look at it this way: First you pay to make it wrong; then you pay to undo what has been made wrong; then you pay again to redo what has been undone; and all the time you are undoing and redoing, you have lost capacity that could have been sold. Then you add the cost of scrap.” (It’s little wonder Bozzone calls rework “the Great Satan of Waste.”)

Preproduction metrics might include the percentage of shop orders released on time and complete—that is, orders that reach production without anything missing: material, tooling and fixturing, clear and comprehensive setup instructions, and more. The last thing production wants is for preproduction to miss something that causes problems in production.

“For preproduction, releasing orders on time is equally important,” Bozzone added, “because when preproduction is delayed and an order is released to the shop late, this overloads the shop, creates chaos, and leads to late deliveries. In fact, [late deliveries from production] are often assumed to be a scheduling problem, when in fact they are not.”

The “front end” would include marketing, sales, estimating, and, in those shops with an extended build cycle, project management.

Similarly, the front end should work to make life easier for preproduction. The faster and more smoothly preproduction can work through job orders, the better the front end is performing. Sales focuses on the shop’s sweet spot, where it can be the most competitive, while perhaps, in an effort to diversify the customer base, exploring how that sweet spot could help customers in other market sectors.

“A danger in job shops is taking orders that do not fit the shop’s capabilities or cannot be delivered by the promised date,” Bozzone said. These should not be quoted, which is difficult to do when the shop is low on work.

With sales focusing on the shop’s strengths, estimators work with drawings that show parts they know the shop can produce; if they don’t know, or if they know the job might be pushing the envelope for production, they talk with their internal customers—that is, the experts in preproduction—and work toward a solution.

Key front-end metrics could include the number of leads generated (including requests for quotation), the percentage of leads that turn into orders and booked business, and the number of new customers.

“New customers are absolutely critical for job shops,” Bozzone said, “because the customer base is continually eroding.”

Note a key metric that hasn’t been mentioned: on-time and on-budget delivery. As Bozzone explained, this is a critical metric for the entire organization, but it cannot be looked at in a vacuum. A job could have flown through production but still be shipped late, just because it was held up in preproduction or front-end processes. So when it comes to performance metrics, the buck for on-time delivery stops not in manufacturing, not in engineering or sales, but at the president or chief executive’s office.

“It’s the president’s job to build an organization that can in fact deliver consistently on time and on budget,” Bozzone said.

Big-picture Thinking

This new structure, Bozzone said, gets people away from compartmentalized thinking. “In a functional arrangement, people tend to think about their function and not how it fits into the overall business process.”

This new organizational model could change that. Bozzone conceded that changing the organization structure alone won’t make every problem go away. But at least it would align everyone’s job with the job shop business process and set the stage for future growth.

Delta Dynamics Inc., www.deltadynamicsinc.com, jobshop360.com.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI