Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Fighting automation boredom at the modern manufacturer

How good ideas, not more parts per hour, improve metal fab shop culture

- By Tim Heston

- February 15, 2021

- Article

- Shop Management

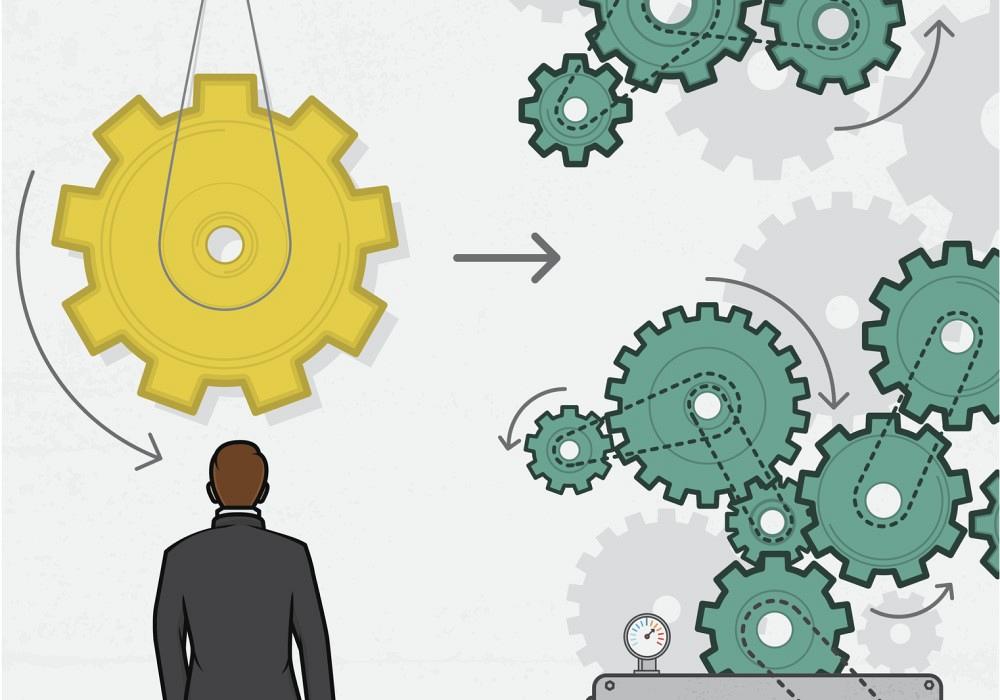

As manufacturing becomes more automated and efficient, operators can be bored out of their skull around the shop. How good ideas, not more parts per hour, improve metal fab shop culture. Getty Images

When metal fabricators tackle continuous improvement, they split tasks into three categories: value-adding, necessary non-value-adding, and unnecessary non-value-adding activities. They aim to eliminate the unnecessary non-value-adding activities to leave time for more value-adding activities, which in turn leads to greater capacity.

This sounds nice, but when you think about how people spend their workdays, complications arise that might be exacerbating the industry’s perennial skilled-labor crisis. At least for certain tasks, from the machine operator’s perspective, adding value can be boring.

Some cutting operations have become so automated that one operator can monitor multiple machines. In programming, the dynamic nests that software creates are good enough for small-batch production, especially for jobs that might never be repeated. Why risk a programming bottleneck by spending hours nesting manually to get the absolute most out of the material, when that nest won’t be run again?

In bending, press brakes with automatic tool change can produce several times as much as their traditional counterparts. Offline programming and simulation can create complicated stage-bend setups that would have been incredibly time-consuming even for the most experienced press brake veteran. Spending time on such complicated setups made sense in a large-batch world, but in a small-lot environment, the effort wouldn’t be worth it without modern software.

In recent years I’ve heard more department supervisors complain about challenges caused not externally by customers but internally by employees: “I wish they would stop tweaking the program.”

Why are they tweaking the program? It depends on the shop and the circumstance, but in some cases, operators might well be producing a program better suited for the job, which is time well spent—as long as they follow established processes so everyone is on the same page. Other times operators tweak programs because feel they have no control over their workday. By producing part after part on state-of-the-art equipment, today’s operators add more value in less time, helping a shop become more competitive and successful; but in doing so, some end up being bored out of their skull.

One root cause might have to do with how fabricators (and all businesses, for that matter) manage value-adding time, unnecessary non-value-adding time, and necessary non-value-adding time. People might be bored because what used to be a “necessary” non-value-adding activity has become unnecessary.

For instance, machine setup is a non-value-adding task with necessary and unnecessary elements, a fact that drives any setup-reduction effort. The low-hanging fruit includes the obvious unnecessary tasks, like walking to the other end of the factory to retrieve a tool.

But there’s higher-hanging fruit too. Over the past 20 years I’ve witnessed more necessary non-value-adding tasks—like machine programming and manual setup creation—become totally or partially automated. Such automation is critical for a fabricator’s competitiveness. Being a Luddite in this business really isn’t an option. Unfortunately, those previously necessary tasks, like learning how to perfect a complicated machine setup, also helped operators learn. Modern tech can’t handle everything, and automatically generated programs can be perfected by those who know what they’re doing. But modern machinery has allowed less experienced people to become very productive.

Fabricators seem to be using several strategies to manage this challenge. First, they push decision-making as close to the front lines as possible without hindering throughput and quality. In fact, many find that doing so actually increases throughput.

For instance, some fabricators have pushed certain scheduling functions down to the department or workcell level. The area lead receives a list of orders for the day, then collaborates with teammates to determine how those orders should be set up and processed on the available equipment.

Input from the front lines is important, too, especially when it comes to implementing change. Last year Jeff Fuchs, president of Baltimore-based Neovista Consulting, described an experience involving longtime machine operators resistant to change. He even noticed areas on concrete floors worn away from the operator walking the same route and performing the same job in the same way over the years and decades.

In this case, giving front-line people—especially those directly affected by the change—a seat at the decision-making table helped. It didn’t make the change painless, but it at least gave operators a voice and, not least, helped them discover how certain changes might benefit others in the plant.

Cross-training also plays a role, helping to break the monotony of all that value-adding time. A cross-trained workforce is a flexible workforce, especially valuable for adapting to rapid changes in demand.

In fact, rapid change has become an industry norm. The question is, who’s entrusted to manage that change? Those who aren’t trusted might find themselves trapped in a boring job, fabricating part after part, with little to no say about how they spend their days. Those empowered to manage change might experience a different workday. Sure, they’ll have boring, value-adding days, processing part after part. But it will be their improvement-spurring ideas, not those boring days, that will define their career.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI